New research has revealed that one of the megaliths at Stonehenge was transported from Scotland, not from Wales as has long been believed. The megalith in question is the ‘altar stone’, the largest of Stonehenge’s ‘bluestones’, which were among the first blocks to have been erected at the site, around 5,000 years ago. Far smaller than the sarsen stones – which were sourced predominantly from Marlborough, around 25km away – the ‘bluestones’ mostly came from a megalithic quarry in the Preseli Hills in western Wales. But the ‘altar stone’ is now believed to have come from the Orcadian Basin in north-eastern Scotland, according to a study first published in the journal Nature. The new research implies that the six-tonne stone was transported at least 750km, a far greater distance than originally believed. It is now thought to have arrived at Stonehenge by sea. Rob Ixer, one of the experts behind the study, told the Guardian that it ‘doesn’t just alter what we think about Stonehenge, it alters what we think about the whole of the late Neolithic [period]’.

The British Museum has admitted that it broke the law in its handling of objects in its care, reports the Times. After it transpired that 2,000 items in the museum’s collection were missing or damaged, the institution commissioned an internal audit, which has now concluded. The report has found that the museum fell short of the standards required by the Public Records Act, which states that museums and libraries must ‘meet basic standards of preservation, access and professional care’, and that their collections be in ‘the care of suitably qualified staff’. The museum has accused Peter Higgs, one of its curators, of stealing or damaging artefacts from the museum’s collection and selling them on eBay. The British Museum is currently suing him in a civil case. Institutions that fall foul of the Public Records Act risk their objects being transferred to another institution, potentially the National Archives, though according to a museum source, there is no suggestion of that happening in this case.

The Italian government is selling off 33 historic sites currently owned or managed by the defence ministry in an attempt to reduce the national debt. The Telegraph reports that the sale will take place in November; among the sites that will be auctioned off include a 16th-century castle in Capua, near Naples, that was built as a military stronghold for the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Also up for sale are several palaces and villas in Florence, Padua and Taranto, and three lighthouses. The sites are currently used by the army, navy and air force, and are said to have a market value of €240m, though might fetch more at auction. Dante Specchia, an architect who works for the FAI, the national trust for Italy, told the Telegraph that this was a missed opportunity to restore these sites under the EU-backed National Recovery and Resilience Plan. ‘We should protect our cultural assets, they are vital,’ he said. ‘Depriving the public of a jewel like the Charles V castle should not be debatable.’

The Rothko Chapel in Houston has closed indefinitely due to severe hurricane damage. Hurricane Beryl, which tore through Texas in July, caused the roof to leak, damaging the ceiling, several walls and three of the chapel’s 14 murals, which Rothko painted for the chapel between 1964 and 1967. The Chapel has recently undergone an 18-month restoration that was completed in 2021 at the cost of $30m. The chapel was added to the United States’ National Register of Historic Places in 2000. Though its closure is indefinite, a spokesperson for the chapel told Hyperallergic that ‘the damage is repairable’ and that the works are undergoing conservation analysis.

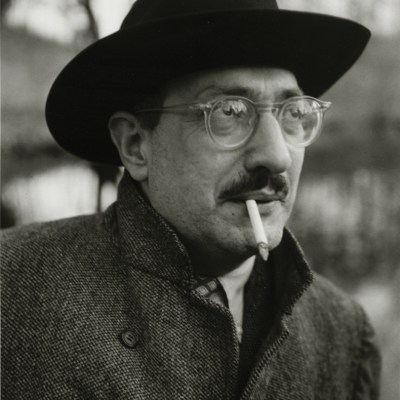

The German curator and museum director Kasper König has died at the age of 80. He is perhaps best known for co-founding the Skulptur Projekte Münster with Klaus Bussmann in 1977, an ongoing project in which high-profile artists are invited to install a sculpture somewhere in Münster every 10 years. The two men intended it as a way of introducing the public to contemporary art in an everyday context. König had been involved in the art world since the 1960s, when he began his career as an intern at the Galerie Rudolf Zwirner in Cologne. In 1965, he moved to New York, where he met artists such as Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol; he served as the New York representative of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, where he curated shows by both artists. In 1987, he set up Portikus, a contemporary art gallery at the Städelschule in Frankfurt, and from 2000 to 2012 he served as director of Museum Ludwig in Cologne. In a statement, the museum says that König ‘shaped the art discourse of the last five decades like no other’.