This review of Is Art History? Selected Writings by Svetlana Alpers appears in the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

At the midpoint of this volume of the selected writings of Svetlana Alpers, we arrive, unexpectedly, on the top floor of the Hamburger Kunsthalle, to contemplate a ceiling decked with intermittently activated typewriters. Contemporary installation art is not Alpers’s usual habitat: she is more often found in front of the great northern European painters of the 16th and 17th centuries, with occasional excursions further south for Caravaggio, Velázquez or Tiepolo. Alpers herself seems surprised in this short piece for Artforum, published in 1996, which, though described as an exhibition review, is less an assessment of the installation (Chorus of the Locusts I and II by the sculptor Rebecca Horn) than an account of Alpers’s experience in stumbling upon it: her initial bemusement, wondering whether there was a ‘reason to bother with something like this’; her hooked attention; the duration of her looking and puzzling; and the pleasure that she took in doing so in company. The afternoon’s atmosphere, she tells us, was ‘a matter of being in play’, revelling in the mode of attentiveness encouraged by museums, in which artworks act as ‘enabling realisations of a state of mind, and […] of a way of being’. It is an account of the circumstances and gratifications of looking and thinking.

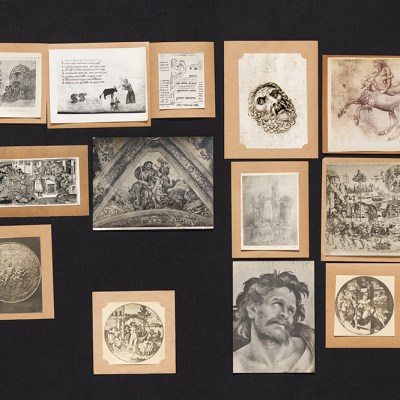

Chor der Heuschrecken I (Chorus of the Locusts I) (1991), Rebecca Horn. Installation view at the Hamburger Kunsthalle. Courtesy D.A.P.

Slight as the piece is (two-and-a-half pages, with illustrations), it marks a significant hinge not just in this book, but also in Alpers’s life and work. Alpers was professor of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley, from 1962 until her retirement in 1994, after which she returned to her native east coast, settling in a Manhattan loft vividly described in Roof Life (2013), her most uncategorisable book. The first piece collected in Is Art History? is ‘Ekphrasis and Aesthetic Attitudes in Vasari’s Lives’ (1960), an astonishingly assured essay on Giorgio Vasari’s descriptions of paintings, written for a graduate seminar taught by Ernst Gombrich. The last reviews an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2023 of the paintings of Juan de Pareja, Velázquez’s enslaved studio assistant. The essays preceding the Artforum piece on Horn – 11 substantial articles and one lecture – testify to Alpers’s professional activities as an art historian, delivered at conferences and published in art historical journals or edited volumes. Footnote-bolstered and learned, they address the concerns of academic peers, situate her work in relation to disciplinary debates and stake out territory and her position within it. The 28 subsequent pieces, all written after retirement, include lectures, catalogue essays and brief exhibition and book reviews, some previously unpublished or printed here for the first time in English, on a newly broadened range of topics, including reflections on photography, gender and race in art, the teaching cabinet at Harvard University; her art-historian mentors and colleagues, and contemporary artists such as Alex Katz, Tacita Dean and Catherine Murphy. The loosened strictures in the second half of Is Art History? refresh the sense of what’s at stake in the magisterial work of the first, and in Alpers’s monographs. The book as a whole testifies to an extraordinary life’s work.

View of Haarlem with Bleaching Grounds (c. 1670–75), Jacob van Ruisdael. Mauritshuis, The Hague

The earlier pieces cast light on the shifting priorities of art history in the second half of the 20th century: from a concern with connoisseurship and the development of style, to the social position of artworks and their witness to the politics and power structures of their contexts. In the famous title essay of 1977, Alpers raises the problem of the proper relation of art to historical context, greeting warmly the rise of interpretations of art in its social and historical circumstances by contemporaries such as T.J. Clark and Michael Baxandall. In 1983, with the literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt and other Berkeley colleagues, she founded the journal Representations, the leading forum for what was called New Historicism, an avowedly interdisciplinary approach that analysed works of literature and art as expressions of the power structures operating in and through a culture, demoting the apparent autonomy of works of art and art history itself. Her field-changing book The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century (1983) itself offered a ‘circumstantial’ account of the images it described, transforming interpretation of the paintings it addressed by seeing them as continuous with scientific illustration, emblem books and experimental observation, writing ‘not the history of Dutch art, but the Dutch visual culture’.

But though Alpers was a galvanising force in such shifts, the pieces here also show her running counter to them. In the interview with Ulf Erdmann Ziegler (begun in 2015; completed in 2022) which closes this book, she describes herself as a ‘contrary person’, and an animating thwartness is everywhere. In the lecture ‘What Are We Looking For?’ (1999) she quotes from the project description for Representations and objects that it ‘considers mediums to be interchangeable’. In contemporary art history, she observes, ‘Artists are more likely to be studied as making careers than as addressing problems’: the singular encounter of a person before their canvas, attempting to work out a solution to difficulties of seeing and representing had been, to her regret, replaced by stories of social ambition. (Her own Rembrandt’s Enterprise: The Studio and the Market [1988], was controversial precisely because it accounted for the particularities of Rembrandt’s art and his imitators in part through the commercial circumstances of its creation.) In ‘Instances of Distance’ (2002) she refuses to critique objectifying images of Native peoples produced by Dutch colonial painters, insisting that ‘Encountering the exotic is not peculiar to the colonial experience. It is a human experience.’ Invited in 1978 to write a piece called ‘Art History and Its Exclusions’ for a panel organised by the ‘Women’s Caucus for Art’, published in 1982 in a volume titled Feminism and Art History, Alpers insisted that it was not ‘the gender of makers’ that mattered to her, but rather ‘different modes of making – North versus South’.

Articulating the difference between these modes of making drives Alpers’s early work. The early pieces in this volume are fired by the same corrective zeal which propelled The Art of Describing: a realisation that the terms of art history had been set by writings on and of the Italian Renaissance, concerned with visual perspective, moral meaning and the representation of action and emotion, making it impossible to get northern European art right. ‘Interpretation without Representation’ (1983) brilliantly shows how previous interpreters of Velázquez’s Las Meninas got the painting wrong by thinking too much of plot and not enough of the problems of representation; ‘No Telling, with Tiepolo’ (1994) argues for Tiepolo’s unsettling of the stories he purportedly represents.

This reorientation of art-historical attention, correcting a bias in the discipline is, however, just a specific instance of something crucial to Alpers’s ways of seeing and writing: the detection of two fundamentally different motives in encountering and representing the world, captured in the title of the early piece ‘Describe or Narrate?’ (1976). Before her seminar with Gombrich, Alpers was a literature student. Her reason for the switch, she says in her most recent monograph, Walker Evans: Starting from Scratch (2020), was her ‘delight in the singularity of a painting’; in ‘What Are We Looking For?’, she phrases it as a ‘love of concreteness’. At the root of her vision is a sense of a split between motives of description and invention at the source of art-making: something which can be parsed on to an opposition between northern and southern European art of the 16th and 17th centuries, but articulates deeper attitudes. Her apparent departure in Walker Evans from her professional expertise in European Old Master painting to the study of a 20th-century American photographer is a further unfolding of her preference for the documentary over invention and fiction.

This reorientation of art-historical attention, correcting a bias in the discipline is, however, just a specific instance of something crucial to Alpers’s ways of seeing and writing: the detection of two fundamentally different motives in encountering and representing the world, captured in the title of the early piece ‘Describe or Narrate?’ (1976). Before her seminar with Gombrich, Alpers was a literature student. Her reason for the switch, she says in her most recent monograph, Walker Evans: Starting from Scratch (2020), was her ‘delight in the singularity of a painting’; in ‘What Are We Looking For?’, she phrases it as a ‘love of concreteness’. At the root of her vision is a sense of a split between motives of description and invention at the source of art-making: something which can be parsed on to an opposition between northern and southern European art of the 16th and 17th centuries, but articulates deeper attitudes. Her apparent departure in Walker Evans from her professional expertise in European Old Master painting to the study of a 20th-century American photographer is a further unfolding of her preference for the documentary over invention and fiction.

If the first half of the book argues for and theorises the conditions of the art of describing, then the second practises it. The more ephemeral, essayistic pieces lack the force of argument, carried through the careful calibration of formidable learning, attentiveness to technique and vivid description which characterise the work of Alpers’s professional life. Instead, they testify to the difficulty and pleasure of trying to get right in words the particular projects of individual painters and thinkers. In the interview, Alpers claims that she writes less for others than ‘to clarify things for myself […] trying to find out what I think’. This is more obviously true in the second half of the book, in which the style becomes (like Rembrandt’s late paintings, about which she writes in a piece from 2015) more gestural, deploying lists, sentences without verbs, single-sentence paragraphs, excerpts from letters and emails: moments which make visible the wrestle to get the experience of looking into words.

In ‘What Are We Looking For?’, Alpers discusses the singularity of Velázquez in relation to his painting Las Hilanderas (The Spinners) of 1655–60. Photo: courtesy Museo Nacional del Prado

In a bravura reading of Velázquez’s Las Hilanderas (The Spinners) in ‘What Are We Looking For?’, published in a longer form in a chapter of The Vexations of Art: Velázquez and Others (2005), Alpers associates Velázquez with the singularidad described by his contemporary Baltasar Gracián as an ideal characteristic of the courtier. This singularidad means something like genius, in its older sense of the inscrutable, unpredictable idiosyncrasies and compulsions of a specific human being and their ability to impose themselves with charisma on the minds of others. Alpers uses it not just to refer to Velázquez, but also as a name for a ‘quality of Velázquez’s paint’ and for something he grants to the human beings he depicts. The ‘singularity’ of a painting was also what lured her from literature to art. This stress on singularity might partially account for her impatience with art history allied to identity politics, as well as for the fact that all of her books on art, after The Art of Describing, have the name of a single artist in the title. It also might explain a terrifying anecdote in a preface written for this collection written by Alpers’s former student Richard Meyer: Alpers’s response to a request for changes from some poor editor at Artforum was to declare: ‘I am Svetlana Alpers, and I am not edited.’

But if a stress on one’s own singularity can lead to breath-taking grandiosity, it is also the condition for a commitment to concreteness and particular vision everywhere on display in this book. ‘What Are We Looking For?’ is printed immediately after Alpers’s encounter with Horn’s chattering typewriters. That slight piece suggests that we might not know, in advance, what object it is we’re seeking; but that the answer to why we are looking, and why looking might be the right way to find what we’re after, rest in the ways that it enables an encounter with singularity: the artwork’s, the artist’s and one’s own. When Alpers wrote about Vasari’s ekphrases, she observed that regardless of whose painting of a particular scene he describes, his terms were remarkably similar: he described the scene, not the painting of it. Alpers’s ekphrases however emphasise the particular act of making: this painting, this gesture, this decision, this moment of looking. This book records Alpers’s life-long engagement with the singularity of art: her own singular, superlative practice, that is, of the difficult art of describing.

Is Art History? Selected Writings by Svetlana Alpers is published by Hunters Point Press.

From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.