There is a question that all authors would kill to avoid being asked: ‘Why do you write?’ In my case, the answer is simple: when I was eight, my grandmother gave me a typewriter. I immediately sat down at it and wrote an essay, about ‘Modern Appliances’, which baffled everyone. I am old enough to have experienced every phase of ‘The Typewriter Revolution’: I had that giant old office Underwood as a kid; my parents threw out their venerable portables when Smith Corona electrics (which smelled of hot oil) came in; I briefly owned an IBM Selectric before it was run over by a jumbo jet; and I was one of the suckers who bought an ‘electronic typewriter’ in the mid 1980s. It required thermal paper on which everything became illegible after a couple of weeks.

‘The Typewriter Revolution’, at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, is a subtle, classy exhibit, its sections divided by panels of reeded glass that might have been found in many an office, 1930–60, and a colour scheme derived from the gunmetal of early typing machines and the bolder reds and blacks of later European designs.

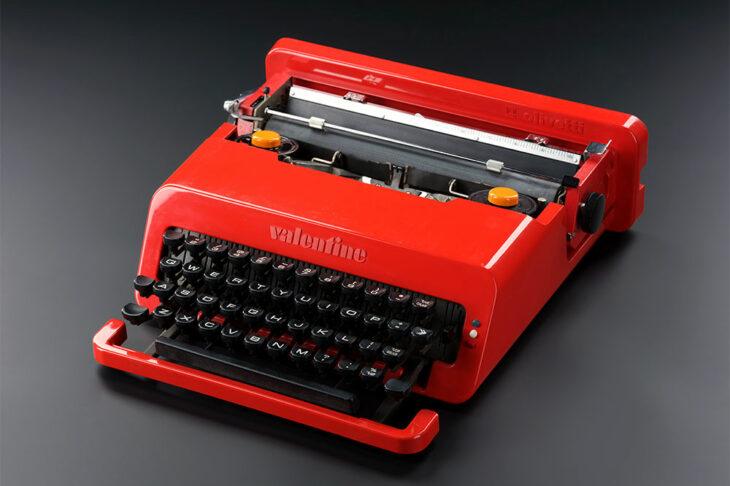

Olivetti Valentine typewriter (c. 1970), made by Olivetti, Barcelona. National Museums Scotland

Apart from some really crackpot ideas about how an individual human being might go about writing a letter using type instead of a pen, the modern typewriter began to emerge in the 1870s. ‘Emerge’ is not quite the word – typewriters were on fire. Business fell on this new technology and devoured it whole. By the 1900s every company possessed a deafening ‘typing pool’ of young women clattering away (boys were found to be lousy typists, as they loafed and were really only angling after the boss’s job). There is no reaction recorded from the armies of manual copyists who vanished from the world overnight with their cylindrical rulers, steel nibs and ink bottles.

As with the history of any technology, some of the more clumsy attempts are among the most entertaining: you can see here a Heath Robinson kind of machine that applied the type to the paper with a jointed rod which moved like a grasshopper’s leg. Quite a few makers tried to avoid linearity, putting the keyboards in semicircles or even in the shape of a ball. There’s an obvious influence of the sewing machine, too, and the piano. The need for an unlimited number of very tiny springs is borne in on one. And strangely enough, many companies persisted in avoiding the use of keyboards, turning out odd-looking things like giant staplers on which one letter is punched, with one hand, before a wheel is turned to the next needed character. Hardly the speediest way to reply to a demand from the Inland Revenue.

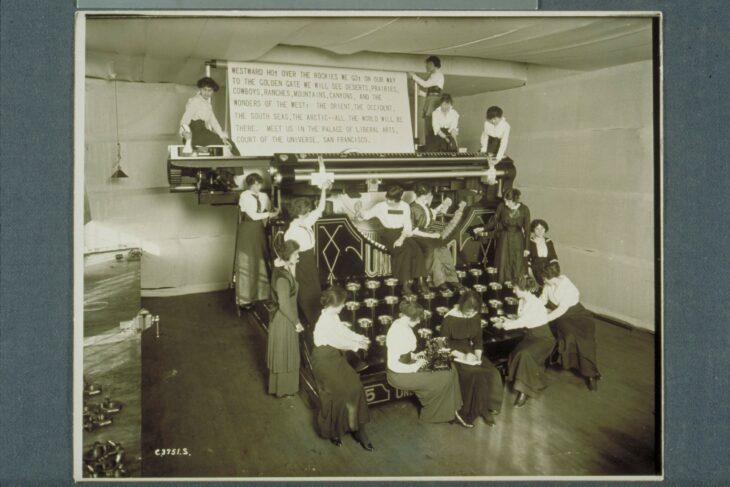

Giant-Underwood-Typewriter-copy The giant Underwood No. 5 created by the Underwood Typewriter Company for display at the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco in 1915. Courtesy Connecticut Historial Society

There’s a wonderful enlargement of a photograph from the Underwood Company, showing a giant typewriter they built as a promotional device in 1912. Each key is big enough for a demure young typist to perch upon – it’s almost as big as business itself. (Where is it now?) There are also films and photos of vast rooms of the past, filled with hundreds of young women typing, and looking pretty bored, in hundreds of starched white blouses. How did those blouses look on ribbon-changing day?

The rapid growth of employment in offices, particularly for girls whose only previous choices of work were domestic service or the factory, occurred at precisely the same time that feminism and suffrage were evolving. Part of ‘The Typewriter Revolution’ is devoted to this political effort. There’s a fascinating display about how the Women’s Social and Political Union, for example, used its members who knew how to type to flood Britain with letters and circulars. An advertisement from the newspaper Votes for Women (1910): ‘Suffragist (ex-prisoner), thoroughly conversant with Woman Question, seeks work. Stenographer (own typewriter). Foreign languages. Organising capacity. Literary experience. Excellent references as Secretary.’

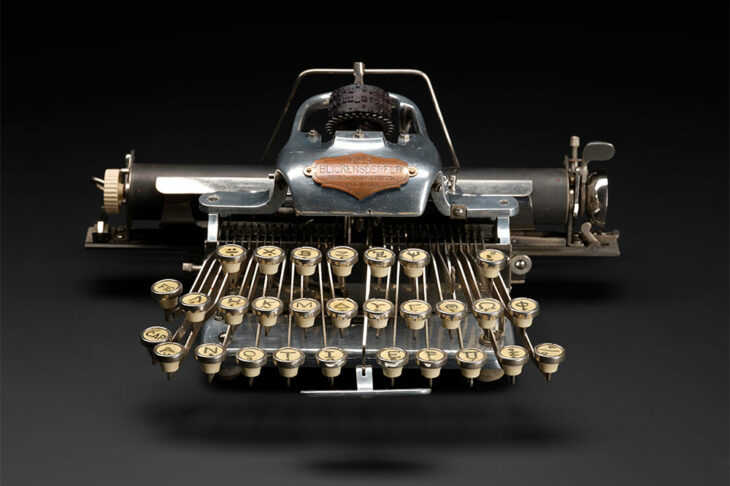

Blickensdorfer No. 5 typewriter (1910), made by Blickensdorfer Manufacturing Company, Stamford, CT and owned by Arthur Bettie, Professor of Greek at the University of Edinburgh. National Museums Scotland

Things change. Decades later, many young women would be advised by their mothers not to learn to type, or at least not to admit that they could, for they would be stuck in a dead-end job for life.

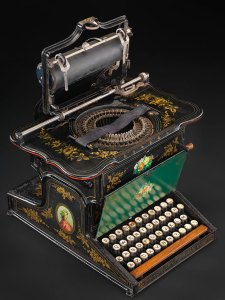

Sholes & Glidden typewriter (1876), made by E. Remington & Sons, Ilion, New York. National Museums of Scotland

There’s an interesting take on writers and their typewriters. Here you can see the ponderous, fearsome-looking electric thing on which Compton Mackenzie wrote the light comedy Whisky Galore. Mark Twain once complained that letters he wrote on his typewriter, an ornate, huge (and hugely expensive) Sholes & Glidden, elicited only responses asking about what it was like to use a typewriter, not the subject he’d asked his correspondent about. He later said the thing was ‘degrading my character’.

Still – all typewriters have this simple, stirring, incontrovertible advantage over everything that has come since: when you write something, it’s there, on paper, already. No typewriter in history ever asked its operator if she wanted to save her work.

‘The Typewriter Revolution’ is at the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, until 17 April 2022.