From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

On 27 June, 1980, Itavia Airlines flight 870 took off from Bologna with 77 passengers and four crew on board. At 20.59, an hour into the flight, as the DC-9 was about to start its descent to Palermo, the plane disappeared off radar screens, broke up and plunged into the Tyrrhenian Sea. At dawn the next day, floating bodies and shards of the wreckage were spotted off the island of Ustica, near Sicily. There were no survivors. The circumstances of the accident, the subject of one of the longest judicial inquiries in Italian history, were surrounded by mystery and scandal. In 2007, the French artist Christian Boltanski was invited to create a memorial to the victims in Bologna, an emotionally freighted installation that frames the huge, gnarled carcass of the salvaged plane.

At first the cause of the crash was assumed to be either mechanical failure or a terrorist bomb. A few weeks later, the burnt-out remains of a Libyan MiG fighter were found in the remote mountains of southern Calabria and there were reports that NATO jets had been seen in the area on the day of the accident. People began to suspect that the commercial plane might have been collateral damage in a secret military operation, hit by a missile perhaps intended to assassinate Colonel Gaddafi, then considered a dangerous, oil-rich sponsor of terrorism. However, a muro di gomma (rubber wall) seemed to surround the case, rebuffing any search for the truth.

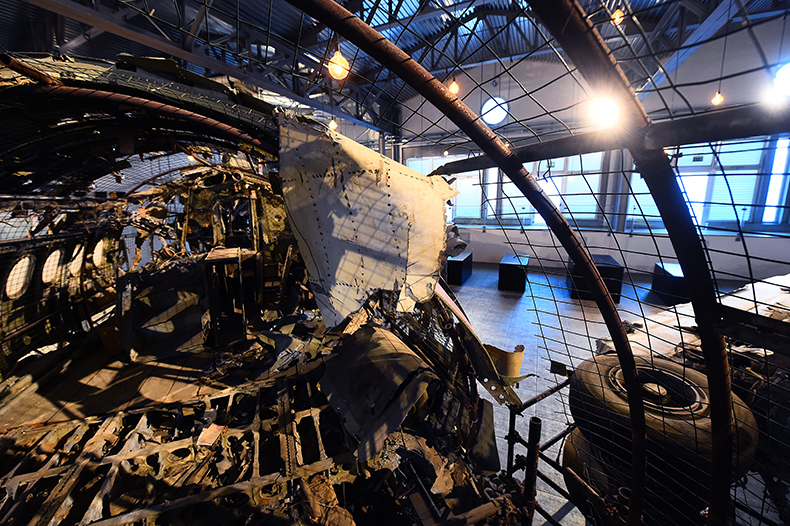

An association of the victims’ relatives, led by Daria Bonfietti, whose brother was on board, campaigned for an independent investigation. After eight years, the remains of the wreckage were recovered from 3,700 metres under the sea and reconstructed by air accident investigators around a metal frame in a hangar in the Pratica di Mare airbase outside Rome. The forensic evidence revealed traces of an external explosion. In 1999, Judge Rosario Priore’s 5,500-page report concluded that the plane was indeed likely to have been downed by a NATO missile and that there had been a criminal cover-up by the Italian military and security services.

The wreckage of Itavia Airlines Flight 870 was recovered off the coast of the island of Ustica in the Tyrrhenian Sea and is now housed in the Museo per la Memoria di Ustica in Bologna. Photo: gpriccardi/Alamy Stock Photo

Nine people, four of them generals, were accused of destroying and withholding evidence, high treason and perjury, but they were later acquitted and to this day no definitive explanation has been given for the incident. As a result, conspiracy theories still swirl around the event. Last year, in an interview with La Repubblica, former Italian prime minister Giuliano Amato accused a French jet of having fired the missile and demanded answers from President Macron, a toddler at the time of the crash. In 1994, a book claimed that Israel was responsible; an article this July in Il Resto del Carlino pointed the finger at the Palestinians.

After the investigation concluded, the victims’ association did not want to see the relic of the plane disposed of; as only 38 bodies were recovered, for many it was the only thing that connected them to their missing loved ones. In 2007, on the 27th anniversary of the ‘Massacre of Ustica’, as this de facto act of war was now labelled, they relocated it to the Museo per la Memoria di Ustica (Museum for the Memory of Ustica), opened in a disused tram depot in the northern outskirts of Bologna. Boltanski, who in 1997 had his first Italian exhibition in the city and was well known for his altar-memorials that tackle themes of death, trauma and the transience of life, was chosen to create this monument.

Boltanski’s father was Jewish, descended from immigrants from Odesa, and for a year and a half Boltanski’s Corsican Catholic mother hid him from the Nazis under the floorboards of their Parisian apartment. The artist was born in 1944, a few weeks after the Allies liberated the city (he died in 2021), and his work speaks to the long shadow cast by the war and Holocaust. In Monument/Odessa (1990), for example, enlarged and cropped photographs of anonymous children, apparently celebrating Purim in France in 1939, are displayed behind a tangle of wires that resemble a family tree, with bare bulbs that illuminate like votive or Yahrzeit candles.

Boltanski’s Ustica installation is his largest permanent work but perhaps, because of its relatively remote location, his least known. In a huge hall, created by the knocking together of three tram sheds and excavating several feet below ground level to accommodate its huge bulk, is the shattered remains of the plane. It lies on a bed of stones, as if still on the sea floor. Two and a half thousand pieces, each of them labelled as in an archaeological dig, have been jig-sawed together to create a haunting, ragged exploded view.

View from the inside of the wreckage at the Ustica Memorial Museum. Photo: Roberto Serra – Iguana Press/Getty Images

Every shard of the plane was first immersed in water to wash off the residues of salt: a kind of baptism. Boltanski imagined the museum as a sacred space, hallowed ground. The axis of the plane forms a cross, and the recovered effects – a crumpled shoe and rusty camera, a snorkel and flipper, a bra and broken tennis racquet, a life jacket and radio – are sealed in nine black boxes that resemble tombs or reliquaries surrounding the twisted fuselage. Before secreting these sacred objects from morbid scrutiny, Boltanski individually photographed them, and these are published as black and white thumbnail images in his melancholy ‘List of personal belongings of the passengers of flight IH870’.

There is no roster of names of the 81 victims on view, but instead an air of generalised tragedy: overhead are 81 naked bulbs that pulsate to the rhythm of breathing, raining embers that represent each lost soul. On the walkway around the sunken hall, from which you view the plane, are 81 pitch-black mirrors, like windows smoked up in the explosion, which reflect visitors’ faces. Behind them are hidden speakers that whisper prosaic but powerful last thoughts as imagined by Boltanski.

‘It feels like Mom is still holding my hand,’ murmurs a young girl faintly; ‘When I get back to Bologna I’ll get the results of my medical exams,’ rasps an old man. Boltanski’s work often blurs truth and fiction, as if it were impossible to distinguish the two in our collective memory. In the museum, there is a centre for research into the accident, an archive compiled by the victims’ families, who still hope for clarity. The museum, Daria Bonfietti says in an accompanying video, is not only ‘a symbolic place of memory’ and record of ‘the long, hard battle to understand what really happened that night in our skies’, but also ‘a stepping stone to uncover the whole truth’.

From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.