From the November 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The Place Vendôme is probably best known – apart from its glinting column that so frequently draws tourists – for being the location of the Ritz Hotel and the centre of the luxury jewellery of Paris. (A jeweller I know will snobbishly say of nearly every luxury shopping street in the world – Bond Street, Fifth Avenue – ‘It’s no Place Vendôme.’) The opening of the Ritz, in 1898, is what changed it all. When César Ritz said that he would provide his visitors with ‘all the refinement that a prince could desire in his own home,’ he introduced a note of indulgence to travel that was all but unknown. The buildings opposite soon responded in kind, filling with businesses designed to serve the very wealthy people who had the sort of disposable income that allowed them to live and travel in style.

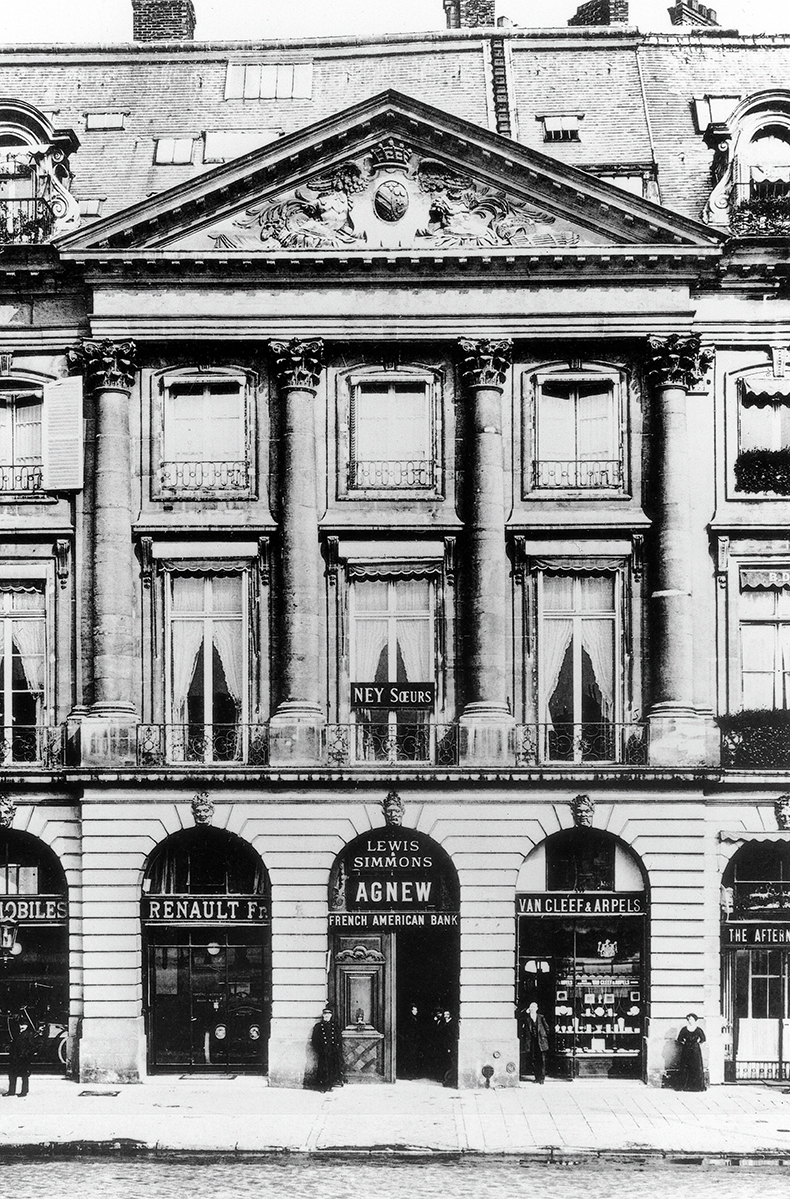

It is a reminder that style and snobbishness change that when Van Cleef and Arpels opened at Place Vendôme in 1906, the neighbouring shop was not a fellow jeweller but the car maker Renault. At the time, travel itself was such a fantasy that a car could be considered in the same breath as a parure. Van Cleef is probably best known as the jeweller who invented the mystery set, that extraordinary feat of engineering that allowed precious stones to be mounted on a piece of jewellery without any visible fastening, throwing open the possibility of playing with design and colour.

A visit to the Van Cleef workshop ratifies the sense of beauty that each piece of jewellery represents. It is located near the Place Vendôme, but I am asked to keep the location secret. Similarly, no photos of the people who work there are allowed, ‘for their own safety’, a stark reminder of both the value of the materials they work with and the fragility of the world that abuts the luxury market. The workshop is on the top floors of its building for the light. When you are working with precious stones light becomes an equally precious resource. The control of that light, how a stone reflects and refracts it, is as much a part of the jeweller’s craft as the soldering of metal.

The front of the Van Cleef and Arpels shop in Place Vendôme, Paris (c. 1906), photographed by A. Salaün

At TEFAF this year, Van Cleef and Arpels showed not only its latest creations but also what it calls heritage pieces. One of these was a bracelet from the 1960s. Mounted in platinum, two stripes of sapphires ran either side of a stripe of rubies. Each stripe was three square-cut stones wide. It was beautiful and made more so by the dexterity of its engineering. Van Cleef is proud of its history, which is why it has recently had the Hôtel de Mercy-Argenteau renovated to be the home of its ‘Ecole’. There, you can learn about jewellery and its history, take workshops and see exhibitions dedicated to different aspects of jewellery making. (The current exhibition is ‘Paris: City of Pearls’, showing from 21 November–23 March 2025.)

There are legendary pieces in the collections: the zip, a necklace based on a zip that was invented by the daughter of the founders, Renée Puissant, in the late 1930s that was said to have been suggested by Wallis Simpson, or the minaudières, feats of engineering that cram an entire beauty regime into a gold or silver box the size of a cigarette case. They were copied by everyone from Cartier to Tiffany. They are so entrancing and varied that Peter Fung, a collector in Hong Kong, felt compelled to amass more than 200 examples.

The gouaché of the Poissons Mystérieux clip. Courtesy Van Cleef & Arpels

Every piece that comes from Van Cleef and Arpels is, of course, made by hand. It is, in some sense, an answer to the question: how do you make something that is flat appear alive in three dimensions? And this is where the mystery really lies. Mystery is probably integral to all jewellery, possibly even all luxury. No one should be able to see the joins between idea and manufacture.

In some ways, the workshop is a giant safe. You enter through a huge, thick, metal door into an airlock before being allowed into the workshop itself. I was not sure what to expect but it was not this. Benches line one edge of the room, in line with the windows. At each bench are five workstations, two on each side and one at the end. The shape of the bench is the same as jewellers have used for the past 200 years. A deep U shape is cut into the bench. Behind this are lines of tools of indescribable fineness for shaping, tooling and joining the metal. At knee level is a leather apron to catch the fragments of gold and silver dust, which are saved, melted and reused to minimise waste.

A craftsman sculpts the gold for the Traversée Mystérieuse bracelet. Courtesy Van Cleef & Arpels

Above the apron, sticking out of the U, is a peg on which each jeweller works the metal. The peg is detachable and each one is specific to the jeweller. Their craft resides not only in the manipulation of the metal but in also using the bench to give them the shape they need to make the metal respond to their will. (Or is that design?) The different incisions, rounding and grooves are testament to each worker’s individual style. Every person working here is in a white coat; it looks more like a laboratory than a workshop. And the feeling of attention is tangible, everyone in the room focused on what they are doing with their hands. The single nod to modernity is a large white tube: a vacuum system to remove the particles that are too light to fall into the apron and could be breathed in – a sign that while diamonds are forever, humans are not.

Next door are the people who apply the stones to the pieces of jewellery. The lapidaries apply the precious stones to the rings, brooches, bracelets or what have you. Again, everyone is in a white coat. The desks are lower, white. These are not work benches but scientific spaces where people work with tweezers on beautifully polished, faceted stones and have lethal things like spirit flames close to hand. Wax is wrapped around the stones so that they can be gripped and manipulated without being damaged. It is a laborious process, but what is time, their work seems to say, when you are dealing with stones that have taken millions of years to form?

A lapidary works on the Poissons Mystérieux clip, which holds the stones using the Vitrail Mystery set technique. Courtesy Van Cleef & Arpels

I watch a man place pink sapphires into a mystery setting. It takes ten years to be allowed to do what he is doing. But if this suggests a workshop of elderly people, that couldn’t be further from the truth. The sense of youth is palpable. Many of the people in this space are in their twenties or thirties, learning the skills from their older colleagues that will allow them to make something as complicated as a zip or a mystery setting. It is a knowledge that is taught through touch and feel rather than writing. It is held by more than one person, so that a sudden death might not rid the world of it.

At one stage I am allowed to walk to a bench where they are working on the latest collection of jewellery. The designs are based on Treasure Island (1883), Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel of pirates and treasure. Van Cleef and Arpels has often taken inspiration from books. A woman has in her hands the figure of Long John Silver, his wooden leg represented by solid gold. His pirate’s dress is full of bezels ready to take his bright blue sapphire costume, and in his hand is a pile of gold and a jewel swinging on a tiny link of a chain. She works guided by a painting or a gouaché. This is how all jewellery designs are done, painted on paper at actual size so that everyone working on the piece can understand what it should look like, the location and shape of each stone present and correct in translucent paint. The light always comes from the same place – top left – not for artistic consistency, but so that everyone who works with it knows which way is the top of the design.

Pirate John clip from the Treasure Island collection, made of white, rose and yellow gold, rubies, sapphires and diamond. Courtesy Van Cleef & Arpels

Perhaps the room that most fascinates me is a small one where three women work sitting a little way away from the windows. This is the polishing room. Two women are working in the way you might expect, but on one bench is a large bunch of cotton threads. They are black with grease – in fact, a type of abrasive paste. A single thread becomes the most intricate and accurate tool with which to ensure every corner of a piece of jewellery sparkles. The polisher rubs the ring rapidly up and down the thread, just as jewellery makers have for hundreds of years.

‘Paris: City of Pearls’ is at the École des Arts Joailliers, Paris, from 21 November–23 March 2025.

From the November 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.