It is hard to imagine a more appropriate way for the National Gallery to mark its bicentenary than with an exhibition that takes as its starting point the acquisition, a century ago, of two of its most popular paintings. Sunflowers and Van Gogh’s Chair arrived courtesy of a new purchase fund for modern art created by the collector and gallery trustee Samuel Courtauld. Both were painted in 1888, and this show focuses on the two critical years the artist spent in Arles and Saint-Rémy in the south of France before returning north in 1890. These were astounding years that produced what most of us think of as the quintessential Vincent van Gogh – not only the sunflowers and interiors, but also the portraits, starry nights, olive groves and cypresses. These were paintings that altered the course of art. Yet this stellar collaboration with international scholars and institutions goes further than playing to the gallery. It presents a fresh understanding of Van Gogh.

Here is the artist as lucid thinker, engaged in developing the ‘art of the future’ and planning how his work should be exhibited, while also relying on inspiration from prose, poetry, music and the art of others, as well as his febrile imagination, to create images of unparalleled intensity and emotion. His aim was to transcend the mere observation of nature and, while motif or sitter was essential to his creative process, veracity was secondary to meaning and effect. Even the portraits of these years were conceived less as likenesses than representations of ideas or archetypes – of poet, lover or salt-of-the-earth peasant.

Starry Night over the Rhône (1888), Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

The artist’s decision to move to Provence seems hardly surprising after the realisation that colour was to be vital to a forging of a new pictorial language. In a Mediterranean climate, the intensity of light and heat amplified all it embraced. For all the advantages the south offered, the move had, however, been prompted by the writings of two of the region’s most famous literary sons, Émile Zola and Alphonse Daudet, and the rich palette of another, Adolphe Monticelli – an artist Van Gogh much admired.

The ‘poet’ of the exhibition’s title is the Belgian painter Eugène Boch, whom Van Gogh met when Boch spent a few weeks near Arles in 1888. Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo that he liked the look of this young man, who had a ‘distinctive face, like a razor blade, and green eyes’, a face he fancied resembled that of Dante. Later he added that he should like to paint a portrait of this artist friend, ‘a man who dreams great dreams, who works like the nightingale sings, because it is his nature to do so.’ He depicted him against a starry ‘infinity’, a background of the most intense blue he could create which would ‘obtain a mysterious effect, like a star in the depths of an azure sky’. He hung the painting on the wall of his humble bedroom in the Yellow House in Arles, a place he envisioned as a home and studio for visiting fellow painters. Next, he imagined the poet’s garden.

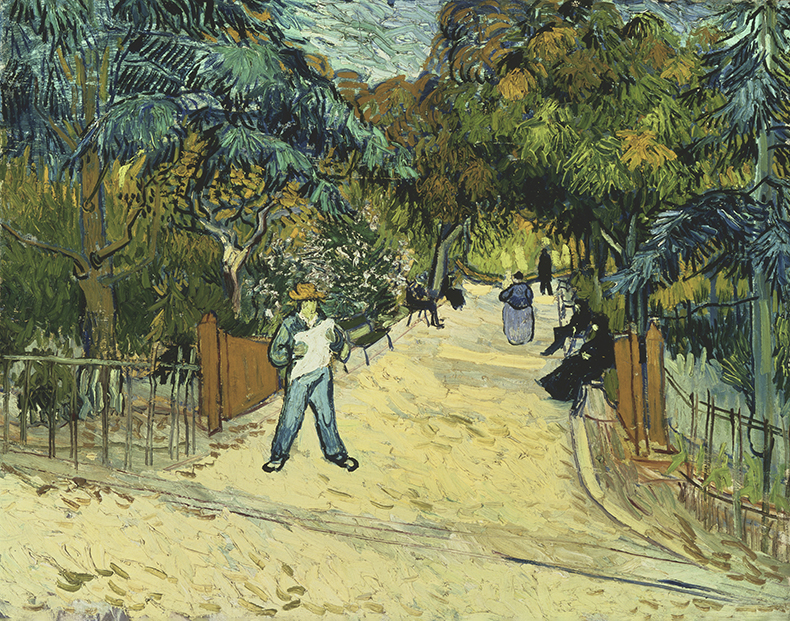

Entrance to the Public Gardens in Arles, 1888. (1888), Vincent Van Gogh. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

For this he set about transforming the rather scrubby public park opposite his home. After reading about Petrarch and Boccaccio, this unpromising place was reimagined as a landscape where Renaissance poets might wander, a conceit reflecting a conscious effort to find poetic subjects that might sell. The Poet’s Garden (Public Garden at Arles) includes a pair of lovers – figures that recur, perhaps wistfully, in many of the works painted at this time. Another new friend, the handsome soldier and womaniser Paul-Eugène Milliet, was lined up as the ideal model for a painting of the subject. While that was never realised, he made Milliet’s portrait and hung it alongside Boch above his bed. He painted himself as a Japanese monk.

No less artfully adapted were the grounds of the psychiatric hospital at Saint-Rémy, where Van Gogh admitted himself after a series of mental breakdowns in 1889. His interpretations of these two gardens, gathered together with vistas across the wider Provençal landscape, painted or drawn with hand-made reed pens, are perhaps the revelation of the show. These images are extraordinary not only for their variety of mood and expression but also for their unorthodox compositions. Low vantage points ensure that three-quarters of a composition is made up of trees against sky or, as in the strangely mesmerising Undergrowth, the tangle of dank weeds under trees. We are feet away from the monumental, twisted trunks of The Large Plane Trees, and plunged into beds of irises. The heavily impasted gestural brushstrokes are thickly woven, roiling the olive groves, skies and rocky hills, and setting the land ablaze under a baking sun.

The Lover (Portrait of Lieutenant Milliet), End September early October 1888 (1888), Vincent Van Gogh. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo. Photo: Rik Klein Gotink

For all the familiarity of Van Gogh’s paintings, the show presents – at least to this reviewer – numerous discoveries. Several works in this surprisingly large exhibition (some 61 works altogether) are drawn from private collections or regional museums, in Europe and the United States. Even those open to the public are not necessarily easily accessible by public transport – the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, for instance, home to the finest holding of Van Gogh’s art and generous lenders here, is in the middle of a national park and is a bus and train from Amsterdam (or a bus from Otterlo). Perhaps the show’s greatest coup, however, is to have secured the loans that have facilitated a partial recreation of the carefully orchestrated hang inside the Yellow House. Crucially, this décoration, as Van Gogh called it, was conceived as an ensemble making conceptual and aesthetic links between the individual works.

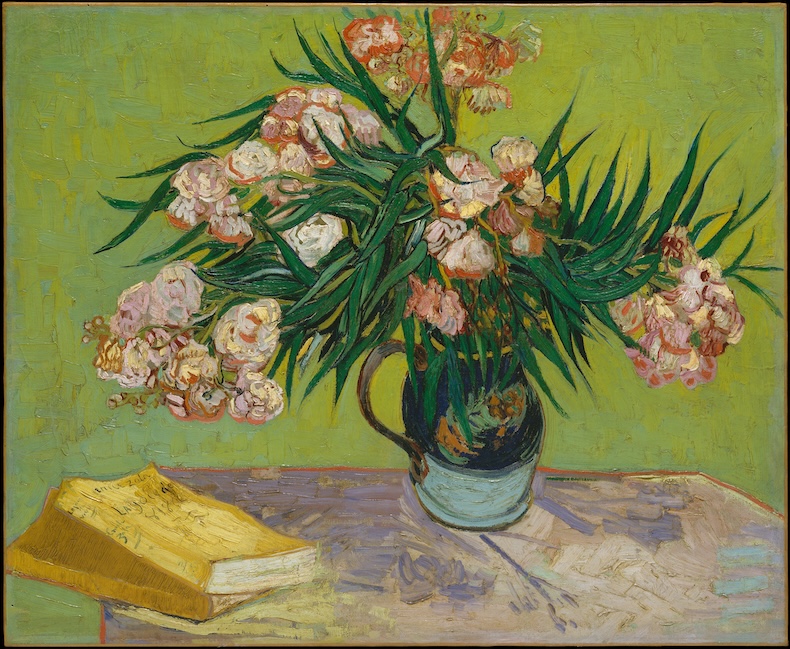

Initially, Van Gogh had intended to decorate his studio with half a dozen Sunflowers, a ‘decoration in which harsh or broken yellows will burst against various BLUE backgrounds’. After various experiments, he alighted on a ‘triptych’ in which two of them would flank La Berceuse (The Lullaby) – a painting of Augustine, the wife of the postman Roulin, rocking a cradle. He later referred to it as a lullaby created in colour and imagined that, together with the joyous sunflowers, the group might bring comfort. The Philadelphia Museum of Art has never previously lent its Sunflowers of 1889. Portrait of a Peasant (Patience Escalier) similarly leaves the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena for Europe for the first time.

Oleanders (1988), Vincent Van Gogh. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It is a bit of challenge to imagine the three canvases together in the modest guest bedroom of the Yellow House rather than spaced along one wall in the grand National Gallery, La Berceuse in its original red painted frame, the others in simple deal. There they would have glowed in the dim light of a house shuttered against the glare of the Provençal sun and give a more authentic voice to a singular artistic vision.

That vision is elucidated in this exhibition’s excellent accompanying publication (exhibition catalogues proper are rare beasts these days given their perceived short shelf-life). Yet the thesis of the show seems stretched a little thin when we are confronted with the paintings themselves. Experiencing these canvases is perhaps simply too overwhelming, the response too personal. The tickets for this show are being released gradually. Book one immediately.

‘Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers’ is at the National Gallery, London, from 14 September–19 January 2025.