From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

With their buttercream impasto and a colour palette somewhere between Miami art deco and The Simpsons, Wayne Thiebaud’s pictures of cakes, hot dogs and deli cabinets provoke and speak of a visceral, almost childish pleasure. They seem to be made from the stuff they represent: glistening, saturated, the paint trowelled on by an artist with the soul of a patissier or food-truck chef. They look delicious – but are they good for you?

Thiebaud, who died in 2021, is this year the subject of two major exhibitions – at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco this month and, in October, at the Courtauld in London. During his long and successful career he was sometimes the subject of backhanded compliments and faint praise: partly a matter of simple intellectual snobbery, given that he had rejected both abstraction and the mechanical aspects of ‘pure’ Pop art in favour of something a shade folksier (he even had a brief internship with Disney Studios as a teenager); partly a function of the sublime incomprehension of East Coast art-world ascetics when faced with a generous plateful of West Coast douceur de vie.

Cakes (1963), Wayne Thiebaud. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

In an essay published to mark Thiebaud’s 80th birthday in 2000, the critic Adam Gopnik argued that he was ‘a modest but not a minor artist’ – more faint praise, arguably. His work lay in an ‘eccentric empirical’ tradition: realism (or, perhaps more accurately, anti-idealism) with a twist. ‘The world is just things, and more things […] and that’s enough,’ Gopnik wrote, channelling Jasper Johns. ‘You love the things for their thingness, not in spite of it.’

In defending Thiebaud from the condescension of chromophobic New York intellectuals, though, Gopnik did him a disservice. Yes, the work had plenty to do with the sheer bounty of post-war America – trays groaning with sticky comestibles, there for the taking at a couple of cents apiece. Happiness was to be pursued, and might be attained, right there on Main Street. But there’s a disquiet and a dislocation in the pictures, too. Thiebaud himself said that window displays initially suggested themselves as a subject because of the formal way they were arranged, not because he had any particular love of cake qua cake. His mastery of a tradition of contrasting shadows that looks back to the Impressionists, and beyond that to Delacroix and even Rubens, results in effects that are not just bold but somehow disconcerting. The very materiality of his paint has a queasiness about it: surfeiting, the appetite may sicken and die. Subjects are presented out of context, in a luminous but curiously lifeless space that’s as much bardo as studio. A cake might have a slice taken from it, but never a bite.

Confections (1962), Wayne Thiebaud. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Katherine Du Tiel; © Wayne Thiebaud Foundation/Licenced by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

A picture doesn’t have to be serious or sad to be interesting, of course, whatever the ascetics might claim. ‘The art world is not much interested in humour […] to its disadvantage,’ Thiebaud once said (see Apollo, September 2017). It’s more that we enjoy the voluptuous delights of his work all the more because it’s seasoned with something else: a squeeze of lemon; a pinch of salt. The small discordant notes in his American rhapsodies make their overwhelming sweetness less cloying. And for all his apparent traditionalism, he’s just as interested in, and interesting about, the relationship between presence and representation in art as any Abstract Expressionist. (In fact, he had a friendly, fruitful meeting with Willem de Kooning during an early visit to New York, admiring the latter’s painterly qualities, and taking his advice on technique – ‘I have a big brush and a little brush’ – to heart.)

Thiebaud sometimes bridled at being typecast as the ‘cake guy’ – though he also embraced the role, illustrating the cookbook Chez Panisse Desserts (1985) and a 1994 edition of Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin’s The Physiology of Taste (1825). Alongside his still lifes he painted powerfully original, almost Escher-like views of the northern Californian landscape, as well as crisply imagined and oddly melancholy figures. One of the latter, Two Seated Figures (1965), appears on the cover of an Italian crime novel I bought in January, La costola di Adamo (Adam’s Rib) by Antonio Manzini. On the same trip I saw trays of minne di sant’Agata, small marzipan breasts commemorating the saint’s mutilation and martyrdom under the emperor Decius. They looked more like a Thiebaud painting than anything else I’ve ever seen in the real world, somehow.

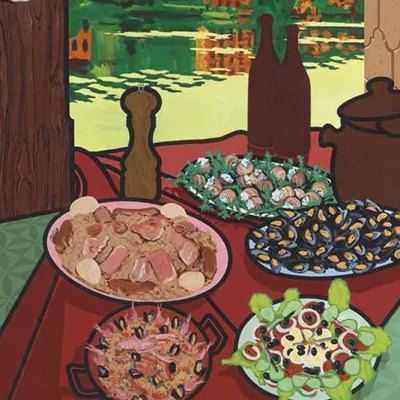

Buffet (1972–75), Wayne Thiebaud. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Katherine Du Tiel; © Wayne Thiebaud Foundation/Licenced by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.