‘The Witch Burns’ is a small but sparkling exhibition in the Fitzrovia Chapel, London W1. Presented by Tin Man Art, a contemporary gallery founded by James Elwes in 2021, the show takes the idea of the witch as a pivot for exploring ideas about womanhood, queerness and the occult. Work by familiar names such as Tim Noble & Sue Webster, Radiohead & Chris Hopewell, sit alongside pieces by up-and-coming artists, including Nooka Shepherd and Zach Toppin. Thoughtful use of the spectacular chapel space, designed by John Loughborough Pearson in 1891 and completed by his son after his death, activates deeper resonances within and between these diverse works.

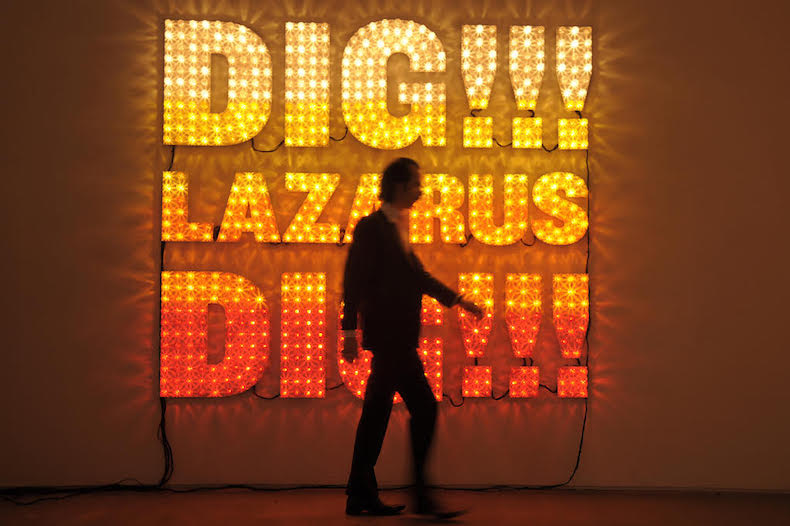

Glowing at the altar end of the chapel, a space traditionally associated with Christian resurrection, stands Tim Noble and Sue Webster’s DIG!!! LAZARUS DIG!!! (2007), a seven-foot high light display used as the album cover for Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ album of the same name. With 775 coloured lamps set to shimmer, it lights up the chapel interior, reflecting off the gold mosaic ceiling and creating the effect of flames or candlelight. Candles also feature in works such as Danish artist Malene Hartmann Rasmussen’s Memento Mori (2024). This ceramic assemblage of dripping black candles and a flame-licked ox skull invokes devil worship and subversive female power, its twisted sacrality underlined by its presence here, in a space dedicated to Christian worship.

Nick Cave photographed in front of an artwork by Tim Noble and Sue Webster that appears on the cover of his album Dig!!! Lazarus Dig!!! (2007). Photo: Charlie Hopkinson; courtesy Tin Man Art; © the artists

Two new self portraits by Sara Berman sit less easily in their surroundings, their muted tones offering a moment of stillness amid the interior’s noisy bling. Hoodie 2 (2024) recalls sensitive Renaissance images of the Virgin Mary in her veil, while Pray (2024) revisits Berman’s interest in the Harlequin as ‘trickster whore’, reclaiming the sexist trope of woman-as-deceiver. Sue Webster’s Birth of an Icon (2024), on the other hand, gains enhanced meaning from its presentation in the chapel. A self-portrait of the pregnant artist, it evokes portraits of the Virgin Mary, albeit with a punk makeover. The painting is accompanied here by a collection of items both personal and mundane – concert tickets, photographs, crisp packets and paintbrushes – suggesting medieval reliquaries associated with saints, or offerings left at pagan shrines by modern worshippers. The inclusion of photographs of the artist as a teenager with mementos from adolescent outings suggests an archaeology of the self: peeling back layers of time and the accretions of biological transformation (into woman, then mother) to unearth a core identity, while also celebrating the son whose arrival is anticipated in the portrait.

Pray (2024), Sara Berman. Photo: the artist; courtesy Tin Man Art; © Sara Berman

Ancestral connection and baptismal themes are to the fore in the multimedia works of Nooka Shepherd. From the watery depths of two miniature ‘heathen baptismal fonts’, The Red Well (2024) and The White Well (2024), emerge faces and hands, sinister and grasping. The oil portrait Back To The Flesh (2023) looks to astrological body maps and animal folklore to evoke a powerful form of relational magic. Zach Toppin’s evocative paintings invoke queer ancestors through a lens of sinister spiritualism: the series Ladye (That such a personality could cease to exist is absurd) (2024) takes the author Radclyffe Hall as inspiration, in particular her obsessive relationship with Mabel Batten (Ladye). The paintings of a blood-stained handkerchief and of a close-up image of a ouija board stylistically evoke retro pulp fiction paperback covers. They offer tantalising narrative hints inspired by Hall’s interest in the occult, and her attempts to contact Ladye’s ghost after the latter’s death in 1916.

Abandon all reason (2016–24), Radiohead and Chris Hopewell. Courtesy Tin Man Art; © the artists

One of the most absorbing pieces in the exhibition is Chris Hopewell & Radiohead’s Abandon all reason (2016–24). This tableau of puppets, fruit and foliage, with a metre-high wicker man at its centre, combines the aesthetic of the 1960s children’s television classic Camberwick Green with the British folk-horror film The Wicker Man (1973). Hopewell originally created the puppets and filmed them over a 14-day span to make the video for Radiohead’s song ‘Burn the Witch’ (2016). The video plays silently on a monitor within the exhibition, but the tableau allows visitors to examine the puppets up close, appreciating details that might otherwise be missed: for example, the beef pie baked from an entire cow, horns, hoofs and all.

‘The Witch Burns’ makes excellent use of its historic location and though the framing device of introducing the occult into a Christian space might sound clichéd, the works on display transcend that limitation, each speaking to the space in ways that develop and enhance their meanings.

‘The Witch Burns’ is at the Fitzrovia Chapel, London, until 12 July.