On 17 November 1869, French illustrator Édouard Riou found himself on the coastline of northern Egypt, sketchbook in hand, as European dignitaries converged with locals at the water’s edge. After decades of back and forth between the French and the Ottoman rulers of Egypt, the Suez Canal was opening for business, and Ferdinand de Lesseps, the canal’s primary developer, had commissioned Riou to create a souvenir album of the event.

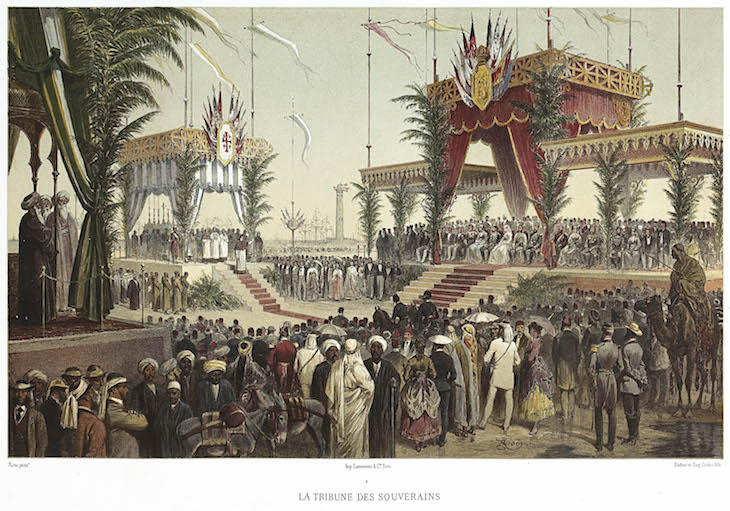

Plate from La Tribune des Souverains by Edouard Riou and Eugène Cicéri (1869). © Souvenir de Ferdinand de Lesseps et du Canal de Suez/Lebas Photographie Paris

The inauguration at Port Said was a moment of triumph for de Lesseps, fully captured by Riou’s Orientalist watercolours, which were published and shared throughout France at the time. Nearly 150 years later, Riou’s illustrations are back in the public eye in Paris, setting the scene at the entrance to the Institut du Monde Arabe’s current exhibition ‘The Epic of the Suez: From the Pharaohs to the 21st century’. The enormous and ambitious exhibition covers more than 2,000 years of canal history, uniting Orientalist painting with multimedia installations, and ancient artefacts with modern scale models and historic maps. Curator Claude Mollard, along with Gilles Gauthier, scientific adviser to the exhibition, decided to begin the journey at this pivotal point in 1869 – a period that has faded from contemporary memory in light of more recent, politicised events surrounding the contentious 193 km waterway, which links the Mediterranean and the Red seas.

Drague décrocheuse (1869–85), Hippolyte Arnoux and the Zangaki brothers. © Archives nationales du monde du travail (Roubaix)

Thirty years after his visit, when excavations around the canal brought the Suez back into the news, Riou revisited the pomp and circumstance of the inauguration in an oversized oil canvas. Imbued with romantic nostalgia, the scene’s ostentatious ceremonial tents are rendered in dreamy blues, pinks and tans, while the masts of tall ships fade into the background mist. Lines of men in local dress stride towards the ceremony on foot, wading through sandy tide pools, with a singular, pre-requisite camel taking part in the ceremony. This painting forms a central part of the exhibition’s opening room, which reflects on the grand European colonial ideas of the late 19th century, and the modern and independent desires of Muhammad Ali Pasha, who ruled Ottoman Egypt from the early 1800s to 1848. Backed by the booming soundtrack of Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Aida, commissioned by Muhammad Ali’s grandson Isma’il Pasha, the extravagant illustrations are offset by early souvenir photographs and black and white views by Polish photographer Justin Kozlowski. His works reveal that the opening of the Suez Canal was ultimately an industrial endeavour.

Fragment de naos dit Naos Paponot (13th century), Egypt. Musee du Louvre. Photo: © Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Christian Decamps

Leaving the inauguration behind, Verdi fades from earshot and the exhibition backsteps 4,000 years for a quick history lesson in the ancient canal. Artefacts on loan from the Louvre help to illustrate the importance of the Isthmus of Suez, a canal which is believed to have first been dug by Pharaoh Senusret III in the 19th century BC. This is perhaps the smallest section in the display, but it accomplishes what the exhibition as a whole sets out to do: reaffirm the Egyptian role alongside the French throughout the saga of the Suez – in this instance, through the sheer weight of history.

Portrait of Muhammad Ali Pasha (1803), Auguste Couder. Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles)/Gérard Blot

From this point, Mollard and Gauthier expertly handle the vast cast of characters at work throughout the subsequent centuries, and the exhibition continues in semi-chronological order to the present day. Having already encountered de Lesseps, we witness his relationship with Muhammad Ali’s son, Sa’id Pasha, and his successor Isma’il Pasha, through plans, agreements, paintings and maps. When construction on the canal began in April 1859, a corvée system of forced labour was implemented; this is illustrated in cinematic form in an extract from Ali Badrakhan’s film Shafiqa wa Metwali (1978), which depicts the dramatic death of an elderly fellahin worker.

The relationship between art and mechanisation is also examined midway through the exhibition, with a prototype of Alphonse Couvreaux’s excavation system displayed alongside four curiously familiar clay models sculpted by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. Bartholdi’s idea for a colossal sculpture at the Red Sea outlet of the Suez took the form of a peasant woman holding a torch aloft. When de Lesseps and Isma’il Pasha did not pursue the idea, Bartholdi transformed the sculpted model into what we now recognise as the Statue of Liberty.

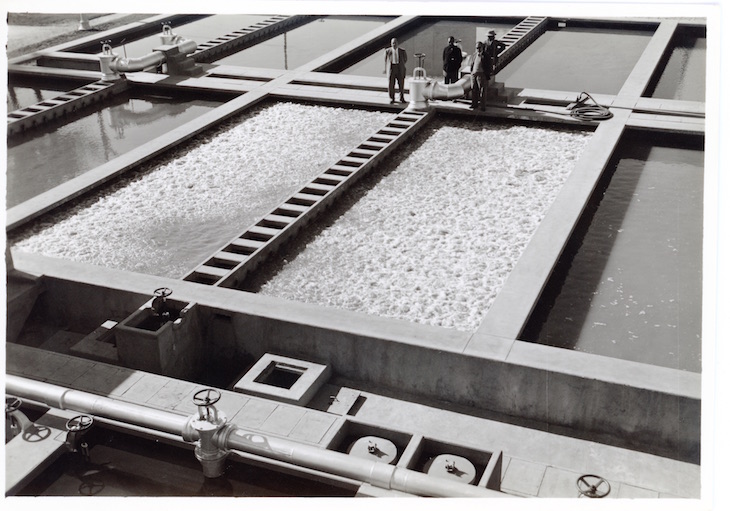

Water treatment – blowing filters in Ismaïlia (1900–50). © Souvenir de Ferdinand de Lesseps et du Canal de Suez/Lebas Photographie Paris

Photography unsurprisingly plays a large role throughout the show, having developed as a medium alongside the rapid industrialisation of the canal. The exhibition dedicates a section to souvenir architectural photographs of the cities of Port Suez, Port Said and Ismailia, but within earshot of these images, the voice of Gamal Abdel Nasser can be heard announcing the nationalisation of the Canal on 26 July 1956. From here, the exhibition is an education in the Suez Crisis of 1956, followed by the Arab-Israeli wars of 1967 and 1973. Maps and media reports are nicely balanced by oral histories and extracts from Egyptian films by Hossam Eddine Mustapha and Khaled El Hagar.

After such deep immersion in the canal’s 19th- and 20th-century history, the exhibition closes abruptly with a glimpse at contemporary statistics detailing its truly global nature. But the inclusion of Mikkel Lorenz’s meditative contemporary video work, shot on the container ship Mary Maersk while in transit down the canal in 2016, gives pause to reflect on Isma’il Pasha’s words some 150 years earlier: ‘No one is more a canalist than I, but I want the Canal to belong to Egypt, not Egypt to the Canal.’

‘The Epic of the Suez Canal: From the Pharaohs to the 21st century’ is at the Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris, until 5 August 2018.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

What the dismantling of USAID means for world heritage