When a museum has a tremendous strength in a field it is usually thanks to an exceptional curator, sometimes several. The Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) is an example. Its renovated galleries for South Asian art reopened last week to display afresh one of the best collections of South Asian art anywhere – a collection that spans a vast swathe of the globe from Pakistan in the west to Indonesia in the east. Its strength is thanks to one outstanding curator whose dedication, knowledge and aesthetic sensibility helped push a then under-appreciated field to prominence. She built up the museum’s collection and also gifted her own – today the combined holdings range from exquisite carved ivories and a Nepalese altar to an entire Hindu temple hall from Madurai. On top of this she negotiated copious amounts of museum space to exhibit it permanently. Her legend lives on today, her inspiration driving the current curatorial team and also stimulating major gifts. Her name is Stella Kramrisch.

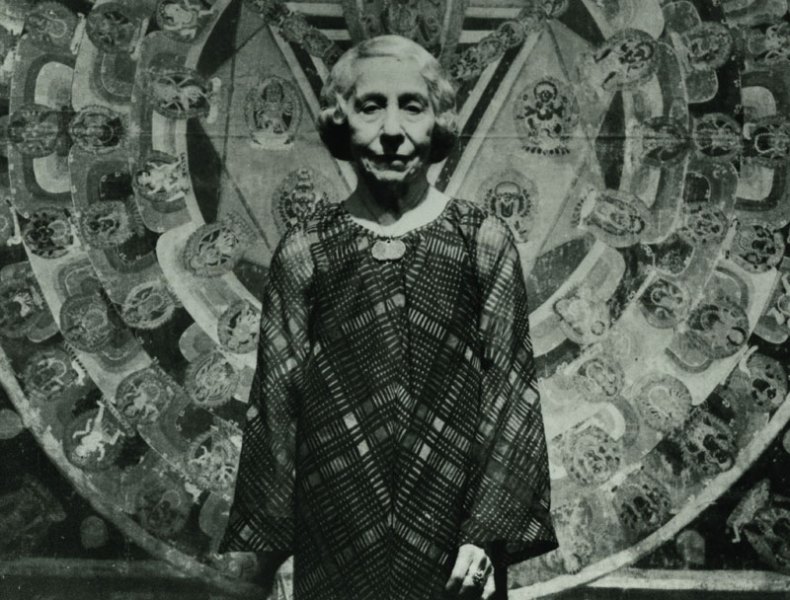

Stella Kramrisch at the museum’s ‘Himalayan Art’ exhibition (1978). Philadelphia Museum of Art Archives

Born in Austria in 1896, as a child in Vienna Kramrisch came upon a translation of the Bhagvad Gita that is considered by many to encapsulate Hindu philosophy. ‘I was so impressed’, she wrote later, ‘it took my breath away’. Thus began a lifelong study of the cultures of the sub-continent, especially Hindu art. The poet Rabindranath Tagore invited her to India where she studied and taught for 28 years. In 1950 she moved to Philadelphia where she would become simultaneously Professor of South Asian Art at the University of Pennsylvania and curator of Indian art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1954–72), then Curator Emeritus until her death in 1993.

Her exhibitions were daring, pushing back accepted boundaries, winning mixed reviews; one such was ‘Manifestations of Shiva’ in 1981. Her many publications, such as Principles of Indian Art about the Hindu Temple, opened complex subjects to a wider audience. And her thirst for buying art – for herself, then for the museum – was unquenchable. Some 20 per cent of today’s collection of more than 4,000 objects came from her personal collection; another 20 per cent she bought while curator at the museum. For the renovation, the whole collection has been newly photographed and put online for universal study and enjoyment, with tools for selecting by theme, geography, date, and so on. Anyone, for instance, can now study and compare two masterpiece sculptures of Avalokiteshvara, Bodhisattva of Compassion, one made in 8th-century Thailand, the other in 5th-century India. She would have like that accessibility.

The newly fitted out galleries open with a tribute to Kramrisch’s life endorsed by some of the masterpieces she sourced; more of her gifts and acquisitions are scattered through the galleries. Darielle Mason, the PMA’s curator of South Asian art, believes it is essential that visitors pause here: ‘She ties it all together. Her life is intrinsic to the collection. By understanding her and her outlook, you can understand the collection.’

Mason also sets out the renovation’s overall aims. ‘There are three things that transform the galleries from before. They are thematic in a dramatic way, each one self-contained but related to the others so you don’t have to follow a route; you pick and choose. Then, the media – text, paper, stone, metal – are mixed up in ways that help you understand underlying themes and philosophies that explain, for instance, why an artist used this or that symbol. Then, visually we have new carefully created vistas.’ As an example, the largest new gallery uses stone, metal, textiles and watercolour pieces relating to Hindu, Buddhist and Jain faiths to create a conversation on the universal themes of nature, reincarnation and enlightenment.

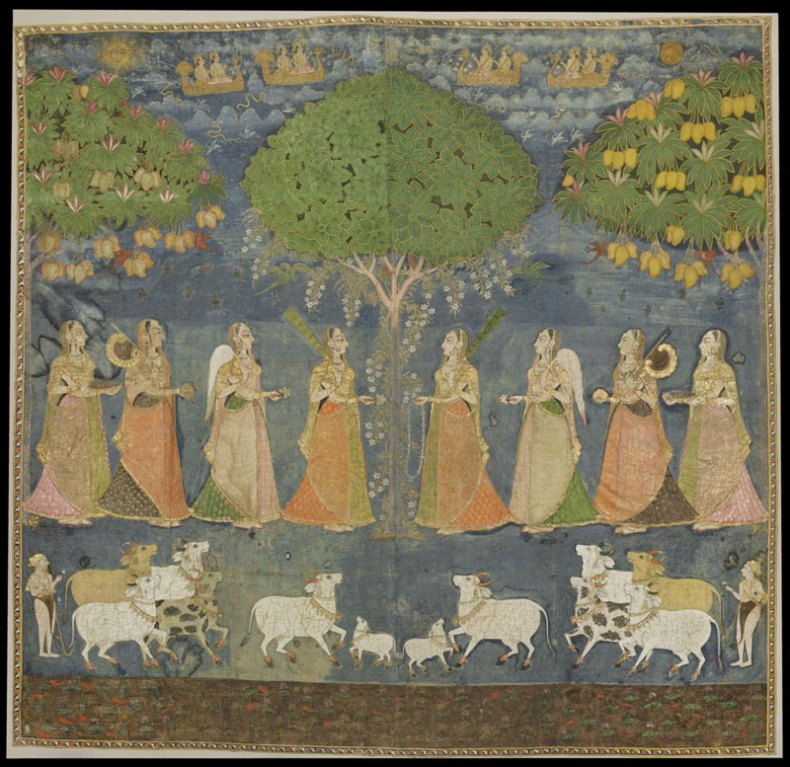

Shrine Hanging with Krishna in Tree Form (Vrikshachari Piccawai) (18th century), Indian, artist unknown.

During the closure the museum undertook some radical conservation work. Some 18th-century ornamental doors made at Lahore were taken apart, conserved, and put together again. They are now back on display in the galleries, accompanied by a film that recounts the project and focuses on woodcarving as an art form. Even more ambitious, some pieces from a large votive stupa that arrived from Bodhgaya in central India in 1921 and have mostly been in storage since, have been studied and reassembled. ‘We have made an intelligent guess for how such a stupa might have looked’, says Mason.

There are some show-stopping new arrivals, too. Peter Stern, founder of the Storm King Art Center outside New York, has given what Mason deems ‘two of the finest pichwais [temple hangings], each eight feet tall. They anchor two of the major galleries.’ Both were made in India; the one from Rajasthan has rarely been seen while the other, from the Deccan area, is on public view for the very first time. Indeed, although all of South Asia is at the PMA, it is the Indian pieces that dominate their new hang – as Kramrisch would perhaps have wished.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)