Since its opening in 1957, visitors to Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge have rung the doorbell before being admitted to a small hall, a vestige of the four tiny slum cottages from which the original house was developed. Not quite a gallery, nor a museum, nor simply a house filled with wonderful things, Kettle’s Yard was founded by the collector and curator Jim Ede (1895–1990), from whose remarkable eye and talent for friendship grew a collection of modern art uniquely displayed in the modest home he shared with his wife Helen. Perhaps most extraordinary of all was Ede’s eagerness to make available not just his collection but his home; every afternoon, almost without fail, he held an ‘open house’, welcoming the public and, principally, students, to enjoy his collection, ‘unhampered by the greater austerity of the museum or public art gallery’.

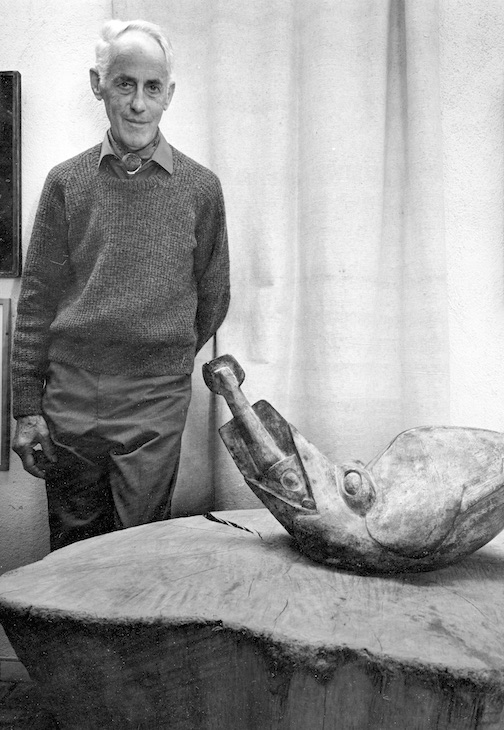

Jim Ede with Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s Bird Swallowing a Fish (1914), Kettle’s Yard, 1972. Photo: Derry Moore; courtesy Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge

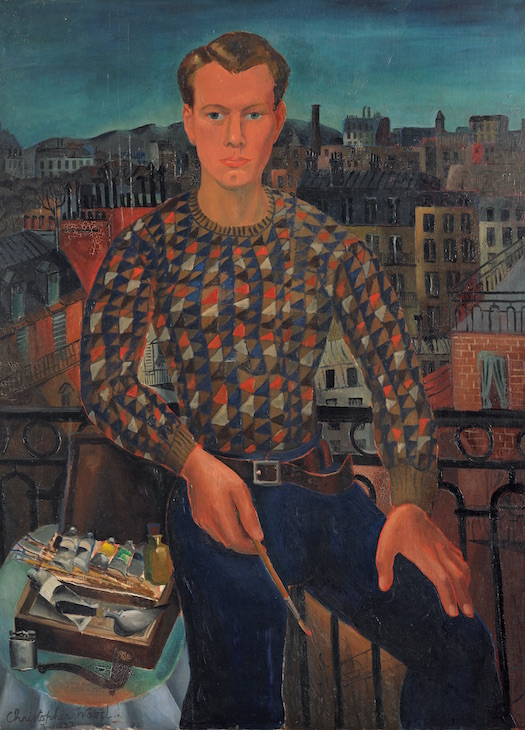

Over 10,000 visitors were recorded in 1971; in more recent years numbers have climbed to an annual average of 70,000, peaking at 86,373 in 2014/15. The figures reflect the continued and growing interest in Kettle’s Yard, which displays around 95 per cent of its surprisingly vast collection and is famous for its holdings of works by modern British artists. It has 100 paintings by Alfred Wallis, of which 40 are on permanent display, 30 by Ben Nicholson, with William Congdon, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, Lucie Rie, Bryan Pearce, and Christopher Wood among the many others represented.

Such popularity inevitably presents a logistical challenge to an intimate setting, particularly one renowned for its lack of museum-style measures protecting its contents from the public. After ten years of planning, Kettle’s Yard closed two years ago to carry out major building works, and reopens next month with an impressive new education wing, exhibition spaces, shop, cafe, and entrance area. The interior of the house has been left untouched, but it sits at the heart of an improved and better integrated visitor experience.

For director Andrew Nairne, who since taking over in 2011 has developed and realised the plans initiated by his predecessor Michael Harrison, the new Kettle’s Yard will place the gallery on an equal footing with the house, offering opportunities and resources befitting the collection’s status. ‘We have this remarkable collection that’s becoming, in a sense, more and more important every year because of the nature of the work, the artists, the stories, our archive and research strengths,’ he says. ‘We have to make sure we have a programme of activity that is of sufficient quality and stature to match this extraordinary house and collection.’

Self-Portrait (1927), Christopher Wood. Courtesy Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge

For those familiar with the old arrangements, the changes at Kettle’s Yard will seem radical. Two generously-sized, environmentally-conditioned galleries will host an ambitious programme of temporary exhibitions on a scale considerably greater than has previously been possible; featuring loans from other institutions, these exhibitions will be in dialogue with the core collection, developing and expanding themes already encountered in the house. An education suite across four floors promises greater engagement not just with schoolchildren and students, but with academics and members of the public from Cambridge and beyond, while an archive of Jim Ede’s extensive correspondence with artists and others will be available to consult by appointment.

Maintaining the integrity and spirit of the original house and collection has been central to the scheme. Visitors will still ring the doorbell to gain access to the house in small groups, having first left their belongings in a new glass entrance area situated in the courtyard, a hub to which they will return on leaving the house – an improvement aimed at encouraging visitors to go on and explore the galleries. The house maintains its fundamental connection to Jim Ede by preserving his instinctively visual and insightful arrangements of art and found, often natural, objects like stones, flowers and shells. Its character continues to be defined by its refusal of museum conventions: all the chairs are there to be sat in, encouraging visitors to spend time looking and contemplating the art, which remains unlabelled and largely unprotected. Displayed at unusual and irregular heights, many paintings are placed at floor level, all the better to be appreciated at leisure by a seated viewer.

Installation view showing Jim Ede’s placement of objects at Kettle’s Yard, in which Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s Toy (1914) sits alongside Spiral of Stones (c. 1958). Courtesy Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge

Objects worth nothing are mixed with objects worth a great deal, creating relationships between the most disparate and unlikely of things: an African pillow-stool is placed in a curiously satisfying arrangement with Christopher Wood’s painting Flowers (1930), and a Moroccan jar. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s Toy (1914) sits on a low table with objects including a shell and a spiral of perfectly round pebbles, challenging notions of worth but more importantly emphasising the value of looking, of seeing art not as self-referential, but as existing in a subtle balance with the world around it. Everything here has a story, from a pair of cracked goblets bought with money from his father intended to cover his rail fare home, to a stone given by one of his daughters. Ede wrote: ‘There are other objects which inform my heart and the whole is a deeply lasting experience.’

Ede described Kettle’s Yard as a ‘way of life’, and his 1984 book of the same name told of the solace he found in the daily routines of dusting, polishing, and rearranging. The house is a self-portrait, shaped by his own history, and specifically his experiences during the First World War, which seem to have led him to want to create secure spaces not just for other people, but for himself. ‘This beautiful bringing together of all these fragments from his life is him trying to hold on to something,’ says Nairne, ‘some bit of security in this challenging and troubled world which he’d experienced at its most extreme first hand in the trenches.’

Even so, to overemphasise the tranquillity of the place is to risk missing just how radical the art is. The collection is testament to Ede’s innate aesthetic sense, which led him to appreciate a number of artists long before they achieved wider acceptance. As an assistant at the Tate Gallery during the 1920s and ’30s (then officially called the National Gallery of British Art), Ede became friends with Ben and Winifred Nicholson, under whose guidance he extended his horizons beyond early Italian painting and ‘rushed headlong into the arms of Picasso, Brancusi and Braque’.

Although he had very little money, Ede forged friendships with artists at home and abroad, and received many artworks as gifts, while others were cheaply bought. He was a rare admirer of Ben Nicholson’s work, acquiring it in sufficient quantities that he was able to make donations to other institutions while maintaining significant holdings at Kettle’s Yard. Writing in 1970, he explained that as his salary was less than £250 per year, if Nicholson remained unable to sell a painting after a year, ‘he would tell me that I could have it for the price of the canvas and frame, usually one to three pounds.’

Tic Tic (1927), Joan Miro. Courtesy Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge

Kettle’s Yard is known as a leading centre of modern British art, but it is in fact thoroughly international, reflecting in part the extended network of Constructivist artists like Naum Gabo whom Ede got to know through British exponents such as Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth. On trips to Paris he encountered Matisse and Chagall, among others, and acquired one of the collection’s great treasures, Joan Miro’s Tic Tic (1927), which the artist gave to him as they drank coffee on a cafe terrace. Now the centrepiece of one of Ede’s characteristic ensembles, the little painting hangs above two glass decanters, on a cider-press screw, the whole inexplicably held in perfect balance.

The core of the collection is undoubtedly its extensive holdings of drawings and sculptures by Gaudier-Brzeska, an artist whose reputation today is in no small way thanks to Ede’s acquisition and promotion of his works in the 1920s. Given that he was killed in the trenches aged just 24, the sheer quantity and sophistication of his output is remarkable, and Kettle’s Yard contains such fine works as The Dancer (1913), Caritas (1914), and Bird Swallowing a Fish (1914). Ten years after his death, the Tate Gallery was reluctant to accept his work even when offered as a gift, and Ede bought many pieces very cheaply, committing himself to the task of establishing his reputation posthumously.

After 20 years of living abroad in Morocco and France, Ede wrote to the artist David Jones in 1956, describing his ambition to find a house in which to put his now sizeable collection, ‘and make it all that I could of lived in beauty, each room an atmosphere of quiet and simple charm, and open to the public’. While he had initially envisaged something more like a stately home, on finding the dilapidated cottages in one of the poorest areas of Cambridge, he set about transforming them with astonishing speed. Sharing was central to his activities as a collector, and Kettle’s Yard continues to loan works of art to students, a practice begun by Ede and testament to his sincere belief in the value of living with art. He also donated a significant proportion of his collection to other institutions, and in perhaps his greatest act of generosity, in 1966 he donated the house and its contents to the University of Cambridge, staying on as resident curator until he and Helen moved to Edinburgh in 1973.

Installation view of Kettle’s Yard, showing the house extension designed by Leslie Martin and opened in 1970. Photo Paul Allitt; courtesy Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge

Furthering his wish to share his collection and to engage young minds in the enjoyment and contemplation of art meant that Ede embraced change willingly, and in 1970, an extension was added to the house. Designed by Sir Leslie Martin, an architect best known for his association with the Royal Festival Hall, the extension over two floors is remarkably sympathetic, and despite being frankly modern, open and airy, it joins seamlessly with the cottages and echoes their enclosed, small-scale spaces. Built to accommodate the collection, but also to allow space for chamber music recitals, the extension was the first of a series of alterations, with some inadequate gallery space added subsequently which also served as a makeshift education area.

Costing £11 million, and funded by multiple donors with major contributions from the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Arts Council, the new Kettle’s Yard is the work of architect Jamie Fobert, whose gallery extension at Tate St Ives was unveiled in October. His solution draws heavily on the 1970 extension, and he describes Leslie Martin’s design as ‘an Alice in Wonderland experience’. ‘It’s a complete change, but so subtle and continuous that you might not notice it,’ he writes. ‘I hope that people will continue from the Leslie Martin building into mine and equally have no idea – that somehow Kettle’s Yard will feel like one, single experience, but a richer one now.’ The new building responds subtly to the existing structure, switching levels in a similar way while the versatile new galleries are lit from the top, echoing Leslie Martin’s lighting in the extension.

The new gallery spaces will allow Kettle’s Yard to stage exhibitions appropriate to its position as a major centre of modern art outside London, and its inaugural exhibition, ‘Actions. The image of the world can be different’ (10 February–6 May), is a bold statement of intent. Its starting point is a series of letters from July 1944, between Naum Gabo, who became friends with Ede in the 1920s, and Herbert Read, in which Gabo writes of the continued relevance and purpose of art in troubled times, his thoughts encapsulated poignantly in one particular sentence: ‘I try to guard in my work the image of the morrow we left behind us in our memories and foregone aspirations, and to remind us that the image of the world can be different.’

Written in the shadow of war, Gabo’s statement had particular resonance, but it is no less pertinent today, in a world fraught with anxieties and conflicts, and in which there is no less need to argue for the value of making and engaging with art. Examples of Gabo’s work will feature along with that of 37 other artists, with his letter a rallying call for artists past and present, to explore the many ways in which art can act in the world. The exhibition intends to draw a broad and diverse audience, and will include music and dance, specially commissioned pieces by artists including Caroline Walker and Jeremy Deller, site-specific works by Cornelia Parker and Idris Khan, and photographs by the young photographer Khadija Saye, who died last year in the Grenfell Tower fire.

It is an exhibition that speaks volumes about the direction the new Kettle’s Yard intends to take, which is broadly that begun by Jim Ede himself some 60 years ago. In a world simultaneously altered beyond recognition, yet curiously the same, Jim Ede’s aspirations remain as compelling as ever, amounting to a firmly held belief in art as a way of life.

Kettle’s Yard reopens on 10 February.

From the January 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why it’s time to stop rediscovering Eileen Gray