A round-up of the best works of art to enter public collections recently

Art Institute of Chicago

Hartwell Memorial Window (Light in Heaven and Earth) (1917), Tiffany Studios

Forty-eight panels of stained glass make up this view of New Hampshire’s Mount Chocorua, an archetype of the American landscape that here basks in a golden sunset, surrounded by streams and woodland rendered in soft, autumnal tones. The image once rose mirage-like over the congregation at the Central Baptist Church (since renamed Community Church of Providence) in Rhode Island, for which it was commissioned in 1917 as a gift from Mary L. Hartwell in memory of her husband. A particularly spectacular example from Tiffany Studios, which operated in New York between the 1870s and the 1930s, the window is believed to have been designed by Agnes F. Northrop.

Hartwell Memorial Window (Light in Heaven and Earth) (1917), Tiffany Studios. Art Institute of Chicago

British Museum, London

Sixteenth-century Italian drug jar

Allocated to the British Museum as part of the UK government’s Cultural Gifts Scheme, this 16th-century jar joins another from the same set already held in the museum’s collection. Known in Renaissance Italy as an albarello, or ‘drug jar’, this example of maiolica earthenware is inscribed with the words ‘GALVZA PESTA’, suggesting that it once held powdered oak galls. Likely produced for the Monastery of Santa Chiara near Siena, the ceramic bears a woman’s bust in profile and is the tenth of 12 surviving jars from its original set to enter a European public collection.

Albarello (c. 1510–30), probably Siena. Photo: Courtesy Sam Fogg, London

The David Collection, Copenhagen

The Aqueduct in Arcueil (1812), C.W. Eckersberg

With its tranquil vignettes of everyday life, this is a clearly romantic portrayal of a community working and living beneath the grand, ascending arches of a 17th-century aqueduct in Arcueil. The painting was completed during Eckersberg’s years as an art student in Paris, some time before he made his name as the father of the Danish Golden Age. Now entering the David Collection, it is permanently reunited with its companion piece, The Longchamp Gate in the Bois-de-Boulogne, from which it was separated in 1837.

The Aqueduct in Arcueil (1812), C. W. Eckersberg. David Collection, Copenhagen. Photo: Bruun Rasmussen

Glasgow Museums

A Highland Chieftain: Portrait of Lord Mungo Murray (c. 1683), John Michael Wright

This splendid portrayal of the 15-year-old aristocrat Mungo Murray as a Highland warrior is of particular historical significance for the subject’s dress. Murray’s woollen doublet is paired with a féileadh mór, or belted plaid – a precursor to the modern-day tailored kilt composed of a thick material that was belted at the waist and worn to the knee by men. As the earliest known full-length depiction of Highland dress, John Michael Wright’s portrait is an important document of Gaelic culture. Acquired by the Glasgow Museums, it is already on public display at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

A Highland Chieftain: Portrait of Lord Mungo Murray (c. 1683), John Michael Wright. Glasgow Museums. Photo: Ross MacDonald/SNS Group

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

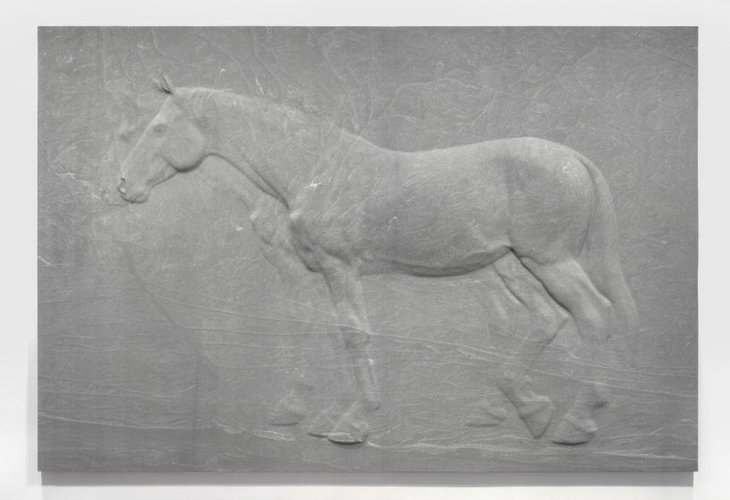

Two Horses (2019), Charles Ray

Instantly evocative of friezes from the classical world, this naturalistic relief sculpture of two horses – one in front of the other – was made last year by the contemporary artist Charles Ray. They are both carved from granite, but one subject is starkly more delineated than the other. With each horse appearing both to stand still and walk up a gentle slope, the scene is enigmatic and serene, a clear contrast to those occupied by their ancestors, who pulled chariots or were ridden, rearing, into battle.

Two Horses (2019), Charles Ray. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: Pari Stave

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C

Alpine Mastiffs Reanimating a Distressed Traveller (1820), Edwin Landseer

This depiction of two mastiffs reviving a traveller trapped in the snowy Swiss Alps established Landseer’s reputation when he painted it, at the age of just 18. Landseer’s gift for the depiction of animals shows clear early promise; while his rendering of the male figure and surrounding landscape is adept, the dogs’ silky coats glisten and their animated expressions are infused with pathos.

Alpine Mastiffs Reanimating a Distressed Traveller (1820), Sir Edwin Landseer. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

St Catherine of Alexandria (c. mid 1630s), Artemisia Gentileschi

A subject that Artemisia Gentileschi would return to several times, St Catherine of Alexandria was the patron saint of philosophers and scholars. She was executed by the emperor Maxentius in the early 4th century; her martyrdom is symbolically referred to here by a palm frond. Compared to some of the baroque artist’s other paintings, this depiction of the young saint gazing pensively beyond the frame has a markedly serene air.

St. Catherine of Alexandria (c. mid 1630s), Artemisia Gentileschi. Nationalmuseum, Sweden. Photo: Cecilia Heisser

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze