From the July/August 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1958, Vincent Price – an art historian and collector as well as a legendary horror movie actor – let Ed Murrow’s show, Person to Person, into his Los Angeles home. Tens of millions of viewers watched as Price proudly pointed out the abstract canvas above his sofa and identified it as being by ‘the great Italian contemporary painter Afro’. New York’s taste for contemporary Italian painting had quickly spread to Hollywood in the 1950s, but Afro Basaldella (1912–76), who usually went only by his first name, was a special case. His connections with the United States were so strong that an exhibition at Tornabuoni Art in 2018 positioned Afro as Italy’s only Abstract Expressionist. The largest exhibition of his work for a decade, in a museum which tends to exhibit international rather than Italian artists alongside the Venice Biennale, is now putting this proposition to the test.

The show locates the Udine-born painter in three cities: Rome, Venice and New York. Opening with a self-portrait of the 24-year-old artist demonstrates the early influence of the Scuola Romana, especially of Corrado Cagli, who lived in the United States during the Second World War. Afro, by contrast, spent the war in Venice and pages from a sketchbook depicting Venetian churches, calli and campi underpin the argument that his soft sweeps of colour owe much to Titian, Tintoretto and Tiepolo.

Yet it is in 1948 that the story told by this exhibition really begins, when Afro participated in the 24th Venice Biennale and painted the abstract work that, in 1949, would appear in the Museum of Modern Art’s seminal show ‘Twentieth-Century Italian Art’. The inclusion of works from the mid 1930s and ’40s in the exhibition emphasises that when Afro’s work was first seen in the United States (and when he first visited New York in 1950), he was already a fully-fledged painter. It also reminds us that Afro – whose work conjures nostalgia and melancholia, moods suggested by evocative titles such as Agosto in Friuli (August in Friuli) and Ricordo d’infanzia (Memory of Childhood) – came of age during the Fascist ventennio.

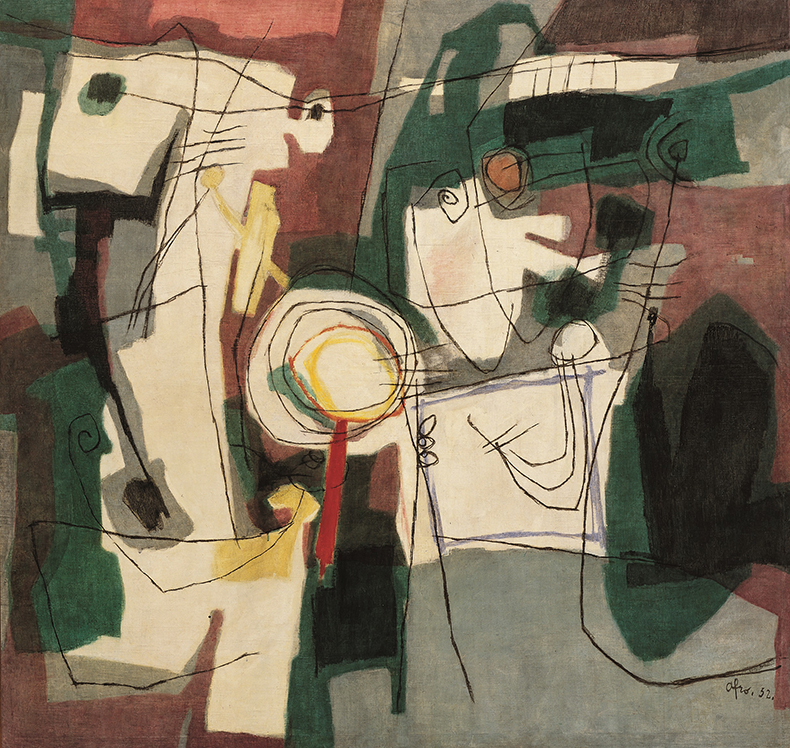

Villa Fleurent (1952), Afro Basaldella. Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Ca’ Pesaro – Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna

The chronological sweep of the exhibition – 40 works taking us across two decades – lays out the painter’s progression. The hint of figurative drawing present in the early abstract works of the 1950s, such as the spidery black lines across patches of white and colour in Estemplare No 3: Villa Fleurent (1952) transforms into expressive brushstrokes in the 1960s, when high-keyed colours appear in works such as in Occhio di lucertola (1960). A decade later, in the imposing Grande grigio (1970), flat colour and geometric pseudo-figurative forms return.

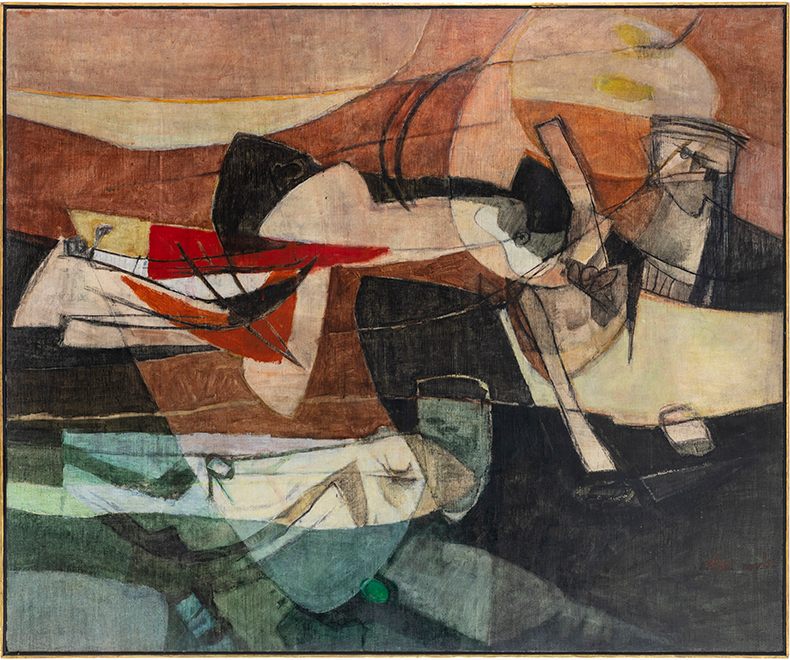

Cronaca nera (1951), Afro Basaldella. Private collection

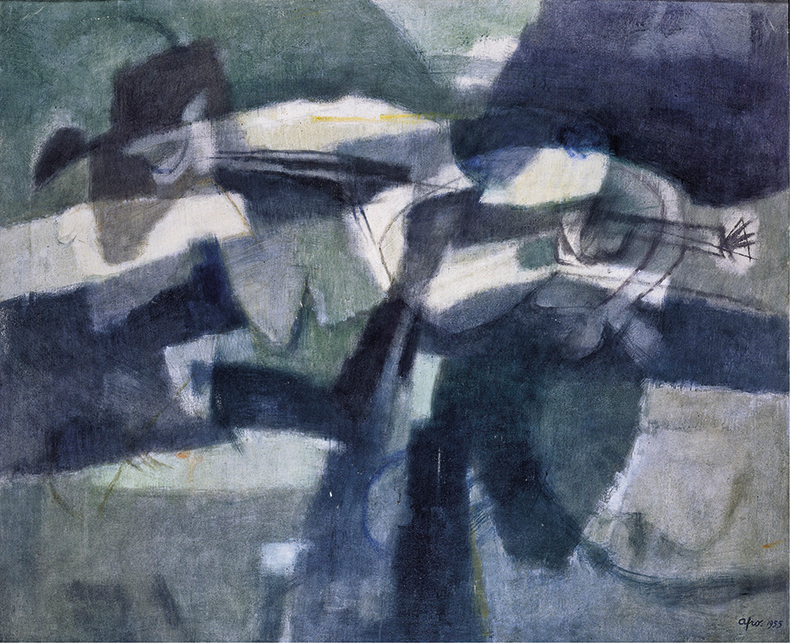

The labels note where each work was first shown, underscoring the importance of institutions in the United States and elsewhere in building Afro’s reputation. In 1955, for example, Afro showed La caccia subacquea (1955) at the Carnegie Institute’s International Exhibition and Cronaca nera (1951) in ‘The New Decade’ at MoMA; both are displayed here next to Figura II (1955), shown at the first Documenta in Kassel. In the same year, Afro’s works could also be seen in Boston, Houston, Minneapolis and Saint Louis, as well as in London, Barcelona and Madrid. These references are often tantalising; we learn that Grande grigio was exhibited at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool in 1971, thus indicating a hitherto unresearched reception in the UK.

La caccia subacquea (1955), Afro Basaldella. Courtesy Fondazione Archivio Afro, Rome

Even more so than institutional figures such as James Johnson Sweeney and Andrew Carnduff Ritchie (both curators at MoMA), it is the gallerist Catherine Viviano who played the leading role in Afro’s career in the United States. A vitrine of archival material documenting Afro’s success begins with a 1949 letter from Viviano announcing her intention to open a gallery and another from 1970 saying she will close it as the market has changed.

As is the case with his friend Alberto Burri, Afro’s time in America is rarely apparent in his subject matter. The exception which proves the rule is the towering diptych Città (1952), in which New York’s combination of grid street plan and soaring skyline converge.

Città (1952), Afro Basaldella. Collezione BNL BNP Paribas, Rome

A greater influence than place on his painting were the friendships Afro made with artists such as Willem de Kooning and Arshile Gorky – both, like Burri, represented in this exhibition – as well as Philip Guston. As Edith Devaney writes in the catalogue, Afro saw himself as a representational painter who chose to make abstract work and gravitated towards Abstract Expressionists who felt similarly to him about figuration. To an extent, these associations liberated him from the myriad groups and affiliations – Fronte Nuovo delle Arti, Forma 1, Gruppo Origine and Movimento Arte Concreta – that developed in post-war Italian art as the battle between abstractionists and realists raged.

In 1952 Afro joined the short-lived Gruppo degli Otto alongside Giuseppe Santomaso and Emilio Vedova. The critic Lionello Venturi wrote that its members ‘are not and do not want to be abstractionists; they are not and do not want to be realists.’ Despite success in America, neither he nor the rest of this group has managed to re-emerge from the dense ranks of Italian post-war painters to achieve posthumous international recognition.

Some Italian critics, eager to foreground the autonomous character of post-war Italian art, were wary of losing Afro to the label of Abstract Expressionism. After the artist’s death in 1976, Maurizio Calvesi wrote: ‘In him was revitalised […] the supreme grace of colour of Tiepolo and Rosalba Carriera, even though he preferred to hear Titian’s name pronounced. And anyone who fails to understand this connection is unable to comprehend the stature and authenticity of Afro, who is wronged by the cosmopolitan comparison with De Kooning’s power or with Gorky’s subtle delirium.’

This exhibition resists pulling Afro too far in any direction, towards either Venetian forebears or American contemporaries. Instead it presents his carefully balanced compositions as the result of his carefully balanced position between figuration and abstraction and between tradition and internationalism; tensions which together make his work so appealing.

‘Afro 1950–1970: From Italy to America and Back’ is at Ca’ Pesaro – Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, Venice, until 23 October.

From the July/August 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)