A visit to the Essex village of Dedham, on the river Stour in the heart of Constable Country, is a summer pleasure. Among the treats on offer, in addition to Constable’s Ascension in the village church, is the Munnings Art Museum at Castle House, a gracious, largely Georgian building in spacious grounds, which was the home of Sir Alfred Munnings from 1919 until his death 40 years later. Munnings was Britain’s finest painter of horses since George Stubbs, regardless of whether they were Gypsy ponies or thoroughbreds, and he attracted discerning patrons across the racing fraternity, from members of the Royal Family to the American multimillionaire, art collector and racing enthusiast Paul Mellon. However, he was a cantankerous and divisive figure, and an after-dinner speech he gave in his role as president of the Royal Academy marked the nadir in relations between traditionalists and advocates of modern art. The occasion was the Academy’s first post-war annual dinner, on 29 April 1949, a grand society event which traditionally preceded the opening of the annual Summer Exhibition; among the distinguished guests present that year were Sir Winston Churchill and the French ambassador. Munnings’s speech, which was broadcast live by the BBC, was a drunken rant – an intemperate attack on modern art in general and Picasso in particular.

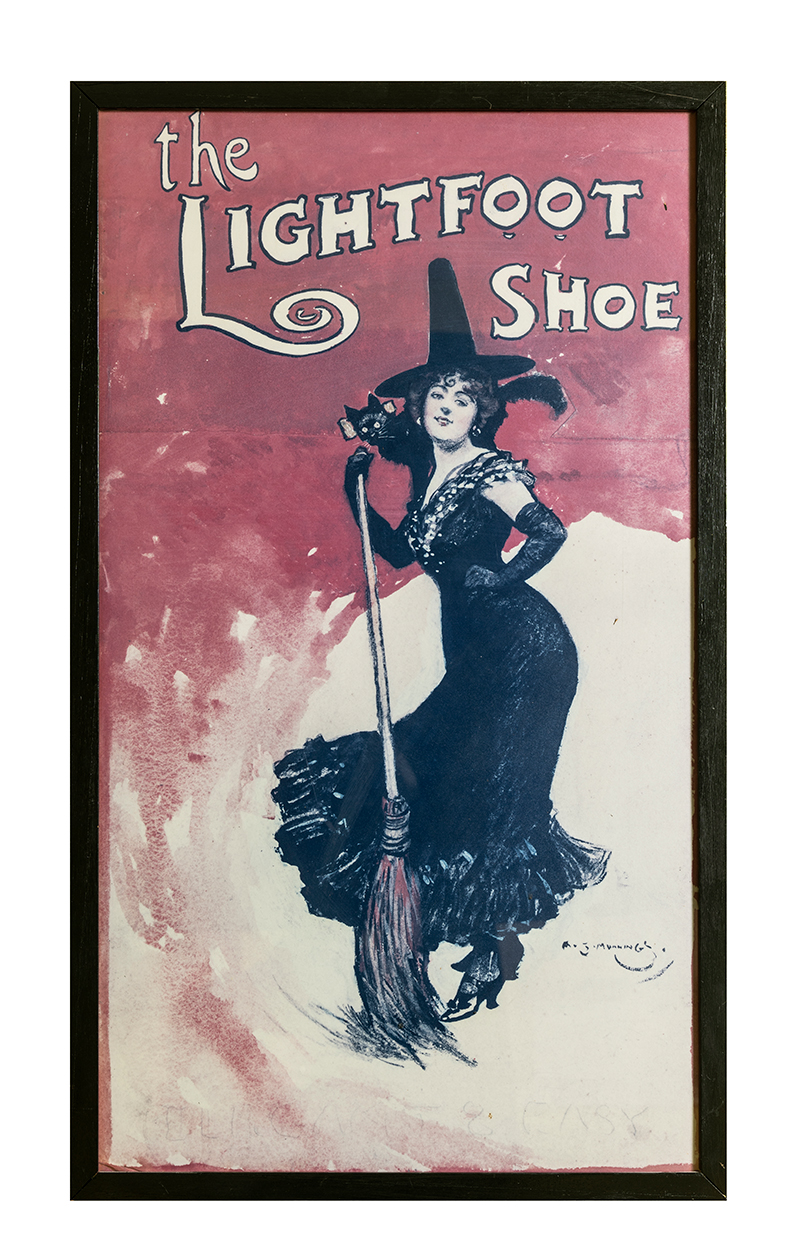

Lightfoot Shoe (c. 1900), Alfred Munnings. © the Estate of Sir Alfred Munnings

For those who think they are familiar with his work, this summer’s exhibition at the Munnings Art Museum, ‘Alfred Munnings: The Art of the Poster’, may come as something of a surprise. As a boy young Alfred, the son of a Suffolk miller, was a compulsive drawer; when he was 14 his family apprenticed him for six years as a poster-artist to Page Brothers, a Norwich firm of lithographers. There he worked a 10-hour day, followed most evenings by a two-hour stint at the local school of art – a rigorous and exhausting training, but still leaving a few hours, at weekends at least, for extramural activities. Reading between the lines, the older apprentices were only too happy to introduce their young colleague to a world of dissipation, of which his speech at the Royal Academy may be regarded as the disastrous – or glorious – culmination, according to your point of view. It is significant that the earliest oil painting in the exhibition, After the Party, a confidently handled study dating from 1897, depicts a weary, hungover youth, paper hat on head, seated at a table strewn – like the floor – with the debris of the previous night’s revels.

After the Party (1897), Alfred Munnings. © the Estate of Sir Alfred Munnings

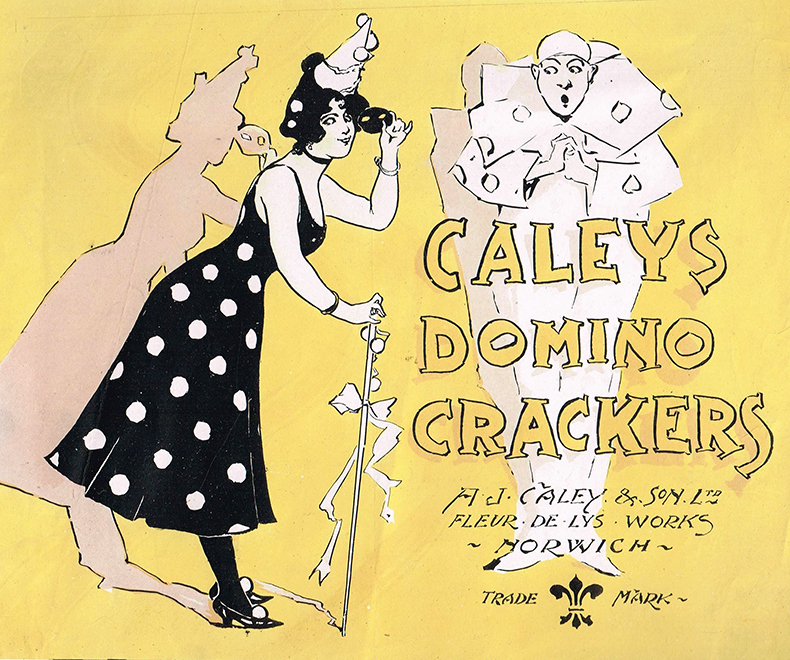

Norwich during the last decade of the 19th century was a typical provincial cathedral city and market town, not so different from Flaubert’s Rouen, if we may judge from Munnings’s gently titillating images promoting the products of Caley’s, a local firm of chocolate and cracker manufacturers. The artists at Page Brothers were clearly familiar not only with the posters of Dudley Hardy and the Beggarstaffs but also, through reproduction at least, with those of Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha, as well as with Randolph Caldecott’s graphic work. Clearly, the light-hearted mood of the fin de siècle was much in the air, with risqué images of the cancan and high-kicking girls, contrasting with those of smugglers and highwaymen in 18th-century costume, inspired by such spine-tingling tales as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island.

Design for Caley’s Domino Crackers (1890s), Alfred Munnings. © the Estate of Sir Alfred Munnings

Page Brothers supplied the advertising and promotional requirements of local firms including Colman’s Mustard, A.J. Caley & Son and Bullard’s Brewery. The larger portion of the current exhibition, however, consists of the box labels he designed for Caley’s various products including not only chocolates and confectionery but also party crackers. The latter were presumably something of a novelty, giving plenty of scope for titillating scenes of giggling girls in charming dresses, often modelled on his cousin May and her young friends who worked for the firm. In contrast to Caley’s wriggle and chiffon, ‘kiss-me-quick’ world of frivolity is an advertisement for Waverley Cycles captioned ‘Waverley Cycles are Satan’s latest sorrow – those who ride Waverley’s defy pursuit’ and depicting a devil seated beside his broken bicycle while another cyclist disappears in the distance.

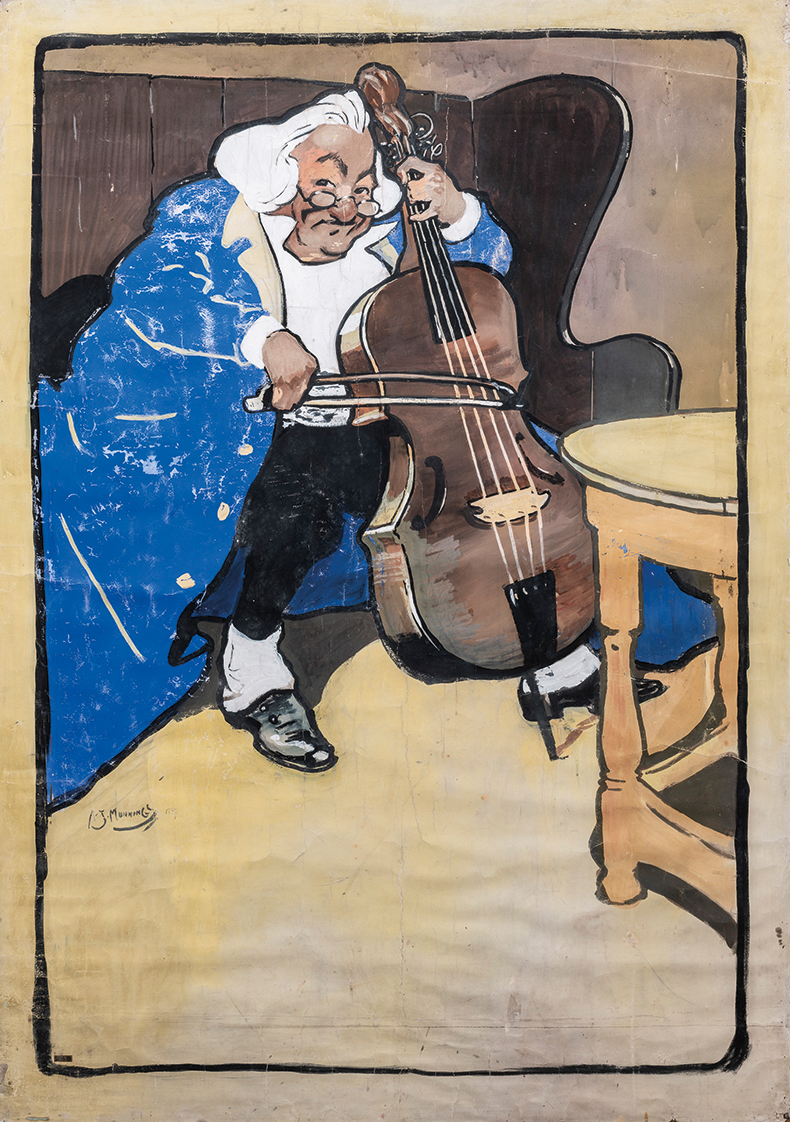

The Solo (1899), Alfred Munnings. © the Estate of Sir Alfred Munnings

Munnings was clearly ambitious and determined not to be intimidated by size, as demonstrated by Lady with a Rose and The Solo, both of 1899, the latter depicting a merry, bewigged Johnsonian figure playing the cello. These two full-scale billboard-type designs, boldly painted in poster colour, were shown in 1899 at the Poster Academy’s exhibition at the Crystal Palace where The Solo was awarded a gold medal – a welcome windfall, but Munnings sold the medal and spent the money on a celebratory dinner. The years of training at Page’s undoubtedly helped him overcome this career-threatening disaster, but left him armed with an all-too-easy facility, which could tip over into vulgarity as in such works as Tagg’s Island (1940), in the museum’s permanent collection. Tagg’s Island was a popular drinking resort on the Thames, and this conversation piece depicting a party of revellers is little more than an enlarged and adult version of a Caley’s chocolate-box label. This is in striking contrast to an earlier painting in the museum’s collection, his al fresco portrait of Daniel Tomkins and his Dog (1898), showing the father of the director of Caley’s, seated in his well-stocked late summer garden: a superbly and sympathetically observed work painted in a manner reminiscent of Tissot. It was probably the last work Munnings painted before the loss of his right eye and is a world away from the glossy effects of his later, seductively attractive brush work.

‘Alfred Munnings: The Art of the Poster’ is at the Munnings Art Museum, Dedham.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why it’s time to stop rediscovering Eileen Gray