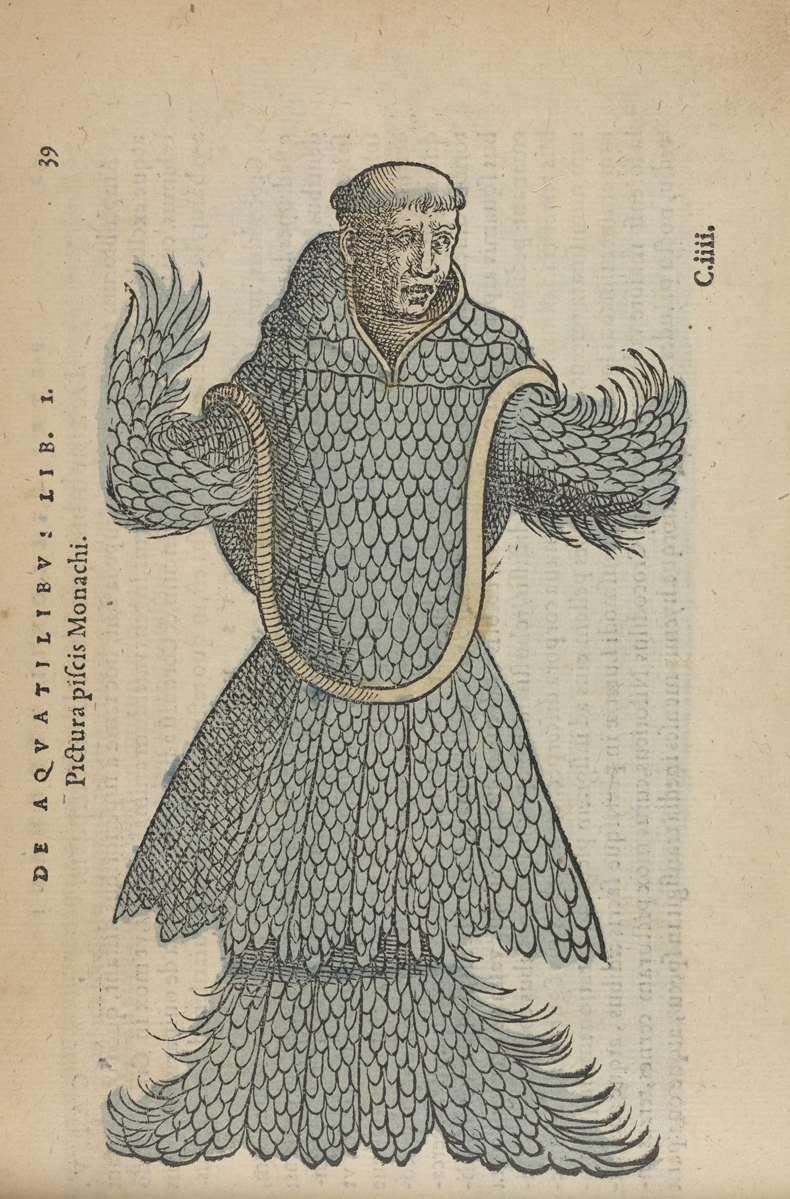

Some visual memories stay with you from childhood. For me, one such vivid memory is of a large tapestry at Oxburgh Hall, a National Trust property in Norfolk. This, part of a series of hangings worked by Mary, Queen of Scots, features animals from all around the world – including one hilarious monkfish, memorably represented as a fish’s tail topped with the head of a monk. Thanks to the British Library, I now know that this image is drawn directly from the book De aquatilibus (1553) by the naturalist Pierre Belon, where it appears with a blue-scaled body morphing into a monk’s habit and tonsured head.

This illustration is made much of in the marketing for the exhibition ‘Animals: Art, Science and Sound’ at the British Library, which offers an amusing view into the history of humanity’s understanding of nature while sending a serious message about the relationship between image, description, observation and knowledge in natural history. As the exhibition makes clear, this kind of knowledge has never been more important than at the present time, when so many species are at risk.

‘Animals’ is a rich and rewarding tour through both the animal kingdom and the British Library’s extraordinary collections. The exhibition presents a 2,000-year story of discovery, destruction and endless wonder. It is divided into four sections focused on particular environments – darkness, water, land and air – each looking at extraordinary or well-known species, the ways they have adapted to their surroundings or the threats they face. The catalogue offers the opportunity to delve more deeply into a selection of the works on display.

The Hip-po-pot-a-mus (1918–20), a record published by the Talking Book Corporation. British Library, London

Large and lusciously illustrated books such as The Birds of America (1827–38) by John James Audubon demonstrate how humans have sought to represent the natural world by recording animals in their habitat. Belon’s monkfish is one cautionary tale about the importance of direct observation, as are some beautiful but implausibly coloured illustrations by Samuel Fallours from 1718, featuring Indonesian fish and crustaceans; these required extensive artistic licence, as the artist had to imagine the colouring lost so quickly in dead fish specimens. Then there is the tale of the bird of paradise: long thought to be constantly in flight and surviving on dew-laden sunlight, thanks to the lack of feet on any specimens sent back to Europe.

Fast forward through time, and the library’s sound archives allow us to hear animals in the wild. Field recordings include early sonograms by the amateur naturalist John Hooper, used to study the behaviour of the nocturnal and largely silent bat. Songs of the Humpback Whale (1970), an album recorded by bio-acoustician Roger Payne, played a crucial role in the international conservation movement to save whales from extinction. The album sold more than 125,000 copies; it remains the most popular nature recording in history. By combining immersive lighting with soundscapes – alongside the richly varied imagery, sounds and texts that make up the show – the exhibition is effective in engaging our senses.

Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (detail; 1705), Maria Sibylla Merian. British Library, London

One underlying theme to emerge from the show is the crucial yet often overlooked contributions made by women. We meet Sarah Bowditch, who illustrated and wrote The Fresh-Water Fishes of Great Britain in instalments from 1828 to 1838; Maria Sibylla Merian, who travelled from Amsterdam to Suriname in 1699 to record the metamorphosis of insects; and Indian artist Sita Ram, who drew South Asian animals for albums collated by Lady Flora Hastings in 1818–20. Recent acquisitions by the library include Evanesco: A Selection of Beleaguered Frogs (2020) by Alicia Bailey, a diamond-shaped artist’s book inspired by the biology notebooks of her great aunt.

This thread continues into the finale of the exhibition, ‘Going Forward’, in which three contemporary women are filmed talking about their work. Researcher Kate Scott-Gatty speaks about her surveys of hedgehog populations for the Zoological Society of London; Miranda Lowe discusses her role as the principal curator of crustacea at the Natural History Museum; the composer Roma Yagnik shares how she drew on the British Library’s sound archives to make a new audio work.

On my visit, the exhibition was buzzing with groups marvelling at the beauty or strangeness of the animals represented within. The British Library has produced a timely reminder of the fragile world in which we live, and the very great risk that we pose to its fauna.

Illustration of a Monkfish from De aquatilibus (Of Aquatic Species; 1553), Pierre Belon. British Library, London

‘Animals: Art, Science and Sound’ is at the British Library, London, until 28 August.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

What the dismantling of USAID means for world heritage