Co-founders, Ishkar, London

Ishkar, a business established by Edmund Le Brun and Flore De Taisne in 2016, takes its name from a desert plant found in Afghanistan’s northern provinces. When burnt, ishkar turns into an ash that can be used to make a pottery glaze of brilliant turquoise. The name suits Ishkar well, given that the work of Le Brun and De Taisne is likewise transformative: for the past eight years, the duo have been partnering with artisans in countries devastated by war to sell their handcrafted objects to people around the world, via Ishkar’s website and east London store. As a result, artisans can preserve endangered heritage crafts, have a stable income and – at a time when tourism and trade may be extremely limited – share their work with a wider audience.

Glassware made for Ishkar by Ghulam Sekhi and other artisans in Herat, Afghanistan. Photo: Kristy Noble; courtesy Ishkar

The decision to launch the business came after the pair spent three years in the Afghan capital of Kabul: De Taisne was working as a consultant for organisations such as the World Bank and United Nations, while Le Brun worked for Turquoise Mountain, the NGO co-founded by Rory Stewart that specialises in the preservation of traditional crafts. During this time they came across work by Ghulam Sekhi, one of just a few remaining Afghan glassmakers. ‘There used to be more than 15 glass workshops in Afghanistan back in the 1970s and ’80s, but due to the conflict and the fact that international buyers presumed that the country was closed for business, they pretty much all shut down,’ says Le Brun. ‘We bought over 5,000 glasses from him and took a bet on them to see if people would like them as much as we did.’

The bet paid off – Sekhi’s glasses were well received, and Ishkar went on to collaborate with artisans in countries including Mali, Pakistan, Iraq, Sudan and Yemen, selling objects such as jewellery, hand-knotted rugs, embroidered cushions and clothing. Collaborations with artists have also come to fruition: Louis Barthélemy worked with Afghan weavers to make limited-edition rugs with motifs of birds and flowers inspired by the 14th-century Gardens of Babur in Kabul, while the painter Christopher Le Brun – Le Brun’s father – created a series of carpets with organic abstract designs.

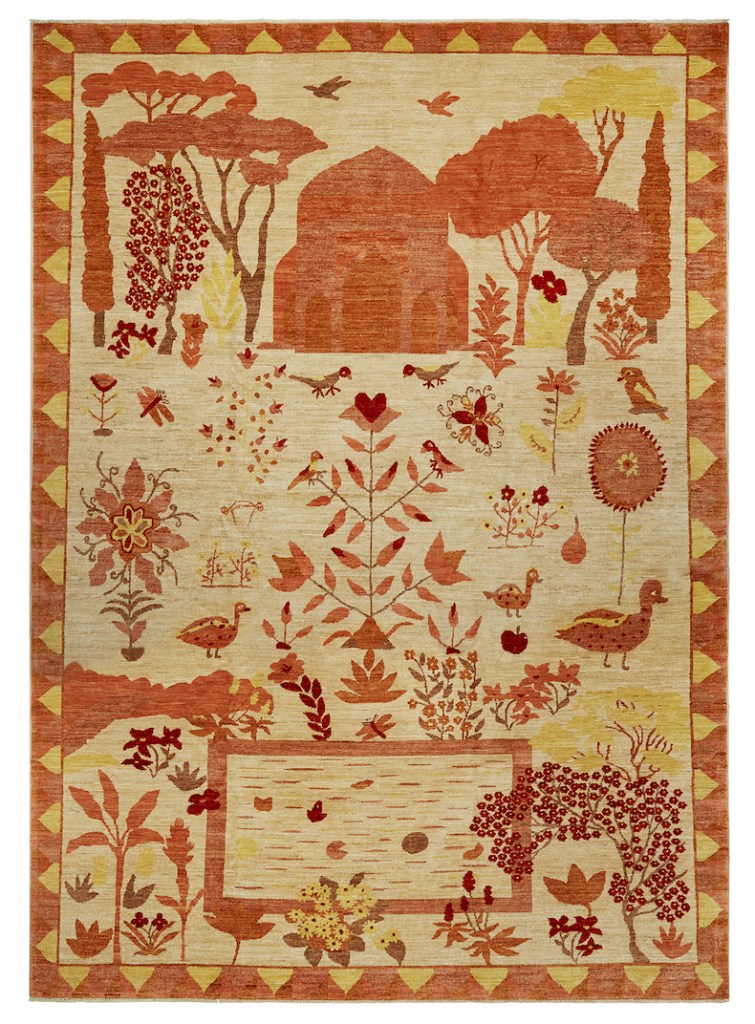

Mughal Petal Drift (2024), a limited-edition carpet designed by Louis Barthélemy and woven by craftspeople in Afghanistan for Ishkar. Photo: courtesy Ishkar

It has become common for Western brands to design items in-house and only bring in artisans at the fabrication stage, but Ishkar takes a more collaborative approach. Products are either developed start-to-finish by craftspeople or co-designed with Ishkar’s creative director. It’s a slow but rewarding process. ‘It might be between six and eight months to get a new product in, just because that’s the time required to have a conversation, receive a sample, and then get something that we think would work,’ says De Taisne.

Glassblower Ustad Nasarullah at work making tableware for Ishkar in Herat, Afghanistan. Photo: Morteza Herati; courtesy Ishkar

Up to now Ishkar has largely been funded by revenue, but a recent drive for external investors means the business is now able to work more closely with trade professionals, such as interior designers, on commissioned work. There’s also plans to spend time exploring other regions where conflict has obscured or diminished making practices. ‘We’re trying to build a universe around the company, which is not just about craft, but also about the stories we tell,’ says Le Brun. ‘We’re so committed to craft as a sector, and I think there’s only going to be an increase in appetite for it as an antidote to our technologically-enabled lives.’

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze