From the September 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

It was in 1942 that the loose group of British artists we now call the Neo-Romantics was first identified. In the New Statesman of March that year, the critic Raymond Mortimer pointed to a resurgence of the romantic spirit in British art. This was characterised by emotional evocations of Britain’s landscape and rural architecture, rendered in a dark and earthy palette. It harked back to Samuel Palmer and William Blake, but in a spirit full of both foreboding and nostalgia. As the artist John Piper had put it, with the looming threat of Nazi invasion in the late 1930s and access to Europe and the United States being cut off by war: ‘Roots became something to be nurtured and clung to instead of destroyed.’ For Piper, ‘this led to another exploration: beauty spots, rivers, mountains, waterfalls, gorges, ruins and cliffs, all the visual natural dramas that we had been taught to shun by Roger Fry and Clive Bell.’

For others, it was the human figure that was important, whether evoked in intense portraits, shown solitary in the landscape or in groups. While no one denies the common thread, traceable through the literature, theatre design, decorative arts, printmaking, photography and fine art of the period, ‘Neo-Romantics’ is somewhat problematic as a unifying term. While some of the artists were friends and lovers, there was no manifesto and little sense of joint purpose. John Craxton, for example, preferred to be defined as a ‘kind of Arcadian’.

The British Neo-Romantics ranged in age from Paul Nash, born in 1889, and John Piper and Graham Sutherland, both born in 1903, to Michael Ayrton and John Craxton, born in 1921 and 1922 respectively. The younger group – including Robert Colquhoun, Keith Vaughan, Robert MacBryde, John Minton and Craxton – shared a sensibility that was shaped by society’s rejection of their homosexuality. Through affinities and associations, the group at times includes Henry Moore (see, for example, his drawings of the London Underground), Prunella Clough, Ceri Richards, Michael Rothenstein and Lucian Freud (who travelled with Craxton to Greece and shared a studio – and, for a while, a lover – with Minton). Despite the slipperiness of the term, curators and collectors have long recognised the value of these distinctively British artworks produced during the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s, before the revolutionary impact of Abstract Expressionism and Pop art.

Harbour and Room (1931), Paul Nash. Piano Nobile, £425,000

In 1987, ‘A Paradise Lost – The Neo-Romantic Imagination in Britain 1935–80’, curated by David Mellor at the Barbican, helped to rekindle interest. According to Robin Cawdron-Stewart, director at Offer Waterman Fine Art, it sparked a steadily developing market led by a small group of well-informed collectors. In June 2011, a still-unassailed world auction record was established for Graham Sutherland with his stark and spiky The Crucifixion (1947), which sold at Sotheby’s London for £713,250 against an estimate of £150,000–£250,000. In May the following year, Sleeping Fisherman (1948) by John Craxton achieved £277,250 (estimate £100,000–£150,000), also at Sotheby’s London. Bonhams recently set a new record with the artist’s Summer Triptych (c. 1958), which fetched £343,300 in London in June this year, against an estimate of £80,000–£120,000. This reflects a new surge of interest in the field – partly triggered, Cawdron-Stewart suggests, by the entry of new collectors, as the prices of works by Francis Bacon and Freud (both hitherto sold at modern British sales) become ever-more unreachable, and by a spate of strong exhibitions and new publications. These include the current show ‘A World of Private Mystery: British Neo-Romantics’ at the Fry Art Gallery (until 29 October), Frances Spalding’s book The Real and the Romantic: English Art Between Two World Wars (2022) and the centenary exhibition ‘John Craxton: A Modern Odyssey’, curated by the artist’s biographer, Ian Collins, which opens at Pallant House this autumn (28 October–21 April 2024). ‘What really makes collectors’ hearts sing,’ Cawdron-Stewart adds, ‘is a great provenance, especially from the collection of Peter Watson, founder of Horizon magazine.’ Watson was a significant patron of Craxton, Minton, Vaughan, MacBryde and Colquhoun.

Bryn Sayles, head of modern British and Irish art at Sotheby’s, suggests that ‘Queer British Art 1861–1967’ at Tate Britain in 2017 boosted the market for Vaughan, Craxton and Minton, by ‘putting their work in new contexts’. She notes the cluster of record prices for Keith Vaughan at Christie’s London in a sale from the collection of Nicholas Goodison in May 2022, in which the large abstract painting Sixth Assembly of Figures (1962) achieved £705,600 (estimate £100,000–£150,000). Pippa Jacomb, head of modern British and Irish art at Christie’s, confirms this current popularity: ‘Currently the works of Keith Vaughan, John Minton and John Craxton are highly sought after. This has shifted in recent years, as the work of Graham Sutherland and John Piper had historically been more in demand.’ Indeed, a 1951 oil by Keith Vaughan will be a highlight of their Modern British and Irish Art Day Sale in October. She notes that a group of works by John Nash (the younger brother of Paul) also performed well above estimate at Christie’s London in January 2020. His Tuscan Landscape (1915) achieved £56,250 against an estimate of £25,000–£35,000. This was a world auction record for the artist, best-known for his visionary landscapes that were the subject of a solo exhibition at Towner Eastbourne in 2021.

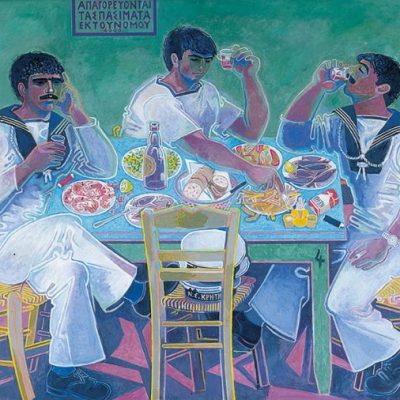

Sleeping Fisherman (1948), John Craxton. Sotheby’s London, £277,250

However, the elder Nash brother continues to dominate. Robert Travers, executive chairman of Piano Nobile, notes the variety and power of Paul Nash’s work across his career, as was seen in a solo exhibition at Tate Britain in 2016. While his First World War-era works are popular with collectors, the auction record for a Paul Nash painting rests with Sotheby’s London for The Two Serpents (Snakes in the Woodpile) of c. 1929–37, which in 2011 achieved £313,250 against an estimate of £250,000–£350,000. Piano Nobile currently has watercolours from the same period available, including a significant Surrealist work from 1931, Harbour and Room (priced at £425,000), which is related to an oil in the Tate’s collection.

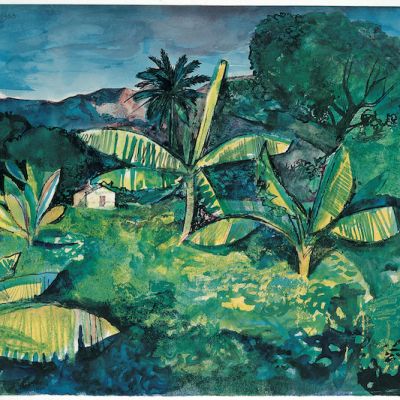

For Travers, one still-undervalued artist is Sutherland. This is a view shared by Matthew Bradbury, formerly director of modern British art at Bonhams and now a director at Osborne Samuel. Besides Sutherland, he points towards a much younger pair, MacBryde and Colquhoun. The key interest, he argues, lies in their works of the 1940s and ’50s that explore the terrible events of the Second World War: ‘These are still underrated, commercially and art historically.’ By contrast, the market for Vaughan and Craxton ‘is arguably stronger than it has ever been’. While 90 per cent of collectors are based in the United Kingdom, there are a number of serious collectors further afield, he reports. Bradbury notes that, with Craxton, collectors seek the male figure: ‘There is huge appetite for his Greek work – this year we have sold three major Greek paintings of single-figure males, all for six figures.’ During a solo exhibition of work by Keith Vaughan at Osborne Samuel in May and June this year, Bradbury was ‘taken aback by the footfall’, with interest shown across the range of Vaughan’s work – from early watercolours to late abstract paintings. ‘He has such broad appeal, it is hard to say what collectors are looking for,’ Bradbury says. At the British Art Fair, the gallery will be showing a quintessentially Neo-Romantic work by John Piper: a vivid, textured evocation of a rugged Welsh mountain, titled Tryfan (1950). The price? ‘£95,000. That is what you have to pay for a good Neo-Romantic John Piper today.’

From the September 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.