From 1961 to 1963, the Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square South in Manhattan hosted the Hall of Issues, a weekly forum that enabled artists, writers, and passers-by to voice their concerns – be they social, political or philosophical – in the form of drawings and statements pinned to a display board. Founded by Phyllis Yampolsky, the Hall of Issues was part activist gathering and part art exhibition. It represents one of many collaborations between the church and local artists since 1959, when minister Bud Scott befriended art students and cemented Judson’s reputation as a hub for avant-garde experimentation.

Just around the corner from its original location, the Hall of Issues is featured in the exhibition ‘Inventing Downtown’ at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery, which charts the emergence of 14 artist-run galleries in downtown Manhattan. Photographs and ephemera relating to the project are displayed alongside documentation of other Judson initiatives, including experimental works by Claes Oldenburg and Jim Dine, and those by lesser-known artists such as Martha Edelheit, whose 1960 psychedelic watercolour, Dream of the Tattooed Lady, anticipates later developments in feminist art. Focusing on historical context and featuring more than 200 works (including paintings, photographs and ephemera), the exhibition represents an immense archival feat by curator Melissa Rachleff. It also offers a welcome opportunity to reconsider the role of art – and artists – during a period of cultural transformation and upheaval.

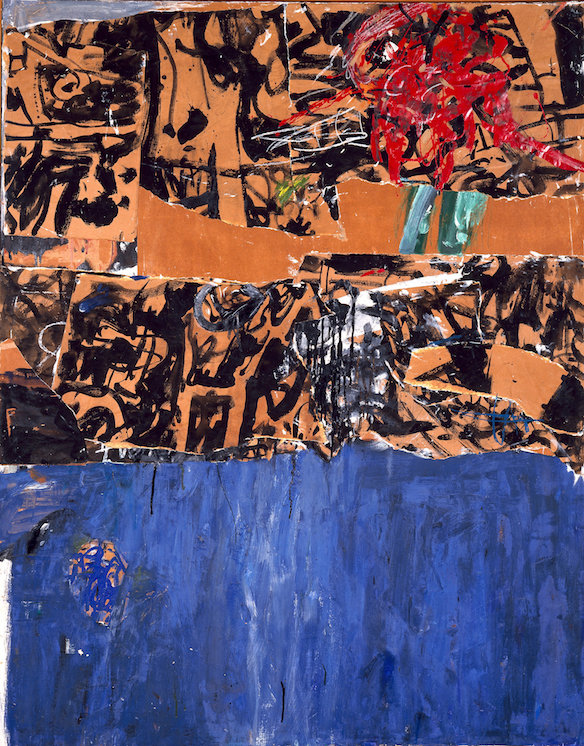

Blue, Blue, Blue (1956), Allan Kaprow. Allan Kaprow Estate; courtesy Hauser and Wirth, New York

The exhibition neatly spans 1952–65, the years between the decline of Abstract Expressionism and the rise of Pop. Abstract Expressionism, shown in galleries uptown, turned the art world’s gaze from Paris to the US in the post-war era. The period examined in ‘Inventing Downtown’, however, has been neglected by art history because of the difficulty in identifying a dominant style. In a 1958 essay on the legacy of Pollock, Allan Kaprow (well represented here) makes clear the need to move beyond rigid artistic categories: ‘Young artists of today need no longer say, “I am a painter” or “a poet” or “a dancer.” They are simply artists.’ Artists during this time instead explored the various possibilities of assemblage, performance, installation, and figurative painting. Rather than aesthetic cohesion, Rachleff focuses on social networks to map a constellation of galleries, venues, and projects that nurtured experimentation and collaboration. While it can feel disjointed, this approach is more inclusive in its attempts to move beyond prescribed art-historical labels, revealing the extent to which women or black artists, for example, contributed to a cutting-edge downtown scene.

A cluster of 13 works on paper by artists associated with City Gallery, founded in 1958 by Charles ‘Red’ Grooms, suggest the coexistence of competing styles and influences. With the exception of one 1963 drawing by Peter Passuntino, all were created in the late 1950s: George Nelson Preston’s charcoal sketch of a jazz performance on Cooper Square, Red Grooms’ frenetic ink drawing of a uniformed figure surrounded by scrawled text, and Mimi Gross’s vibrant street scene, are each inspired by life in New York. The Spiral Group, composed of African-American artists who debated the relationship of art to racial identity and politics in the early 1960s, embraced a range of styles, from the painterly abstraction of Norman Lewis and Hale Woodruff, to Romare Bearden’s collages. Emma Amos’s 1965 Pop self-portrait, Without Feather Boa, is one of the exhibition’s gems.

79 Park Place, from the series The Destruction of Lower Manhattan (1967), Danny Lyon. Courtesy the artist and Magnum Photos; © DannyLyon/Magnum Photos

With the exception of the Green Gallery, all of the spaces featured here were run by artists, who paid fees towards operating costs and assumed administrative roles. This co-operative model granted a level of creative freedom now all but lost; these galleries were able to take advantage of cheap rents, proximity to art schools and community centres, and available space in tenement buildings. In addition to the eventual commercialisation of the art world, urban renewal projects in the post-war period vastly affected downtown neighbourhoods. Such was the fate of 79 Park Place, a five-story building that was almost entirely occupied by artists in the early 1960s before it was razed to make way for the World Trade Center. Danny Lyon memorialises this space in a 1969 photograph from his series The Destruction of Lower Manhattan. If the only constant is change, ‘Inventing Downtown’ represents an ambitious act of recovery and a reminder of the ways in which artists struggle, and survive, amid political and civic unrest.

On 20 January this year, Yampolsky revived the Hall of Issues as part of the #J20 Art Strike against the inauguration of Donald Trump. As in the 1960s, today’s atmosphere is ripe for a political and even irreverent art. The past 12

months have seen the rise of artist-initiated platforms that extend their influence beyond the white cube, such as For Freedoms, an artist-run super PAC founded by Hank Willis Thomas and Eric Gottesman, and the collective Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter, facilitated by Simone Leigh. This is not to mention more ad-hoc ventures like the colourful, post-election transformation of NYC subway stations lined with Post-it notes, each one an affirmation of the city’s commitment to inclusiveness. The projects featured in ‘Inventing Downtown’ suddenly seem important and unexpectedly topical in their engagement with themes of war and capitalism, gentrification and urban life.

From the March issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)