When the photographer Robert Freeman died in November last year, at the age of 82, he left behind a substantial, albeit disorderly, archive. But within weeks, his life’s work had gone missing – stolen from the sheltered accommodation in south-west London where he spent his final years. ‘Bob kept everything,’ recalls Monica Godwin, executor of the Freeman estate. ‘He was such an artist that he didn’t want to let go of any of his babies.’ His fastidiousness did not, however, extend to keeping his records in manageable order. His archive was housed in a haphazard arrangement of boxes that filled an entire room of his home; the closest thing to a catalogue was stored on a CD-ROM, which has disappeared along with the rest of the collection.

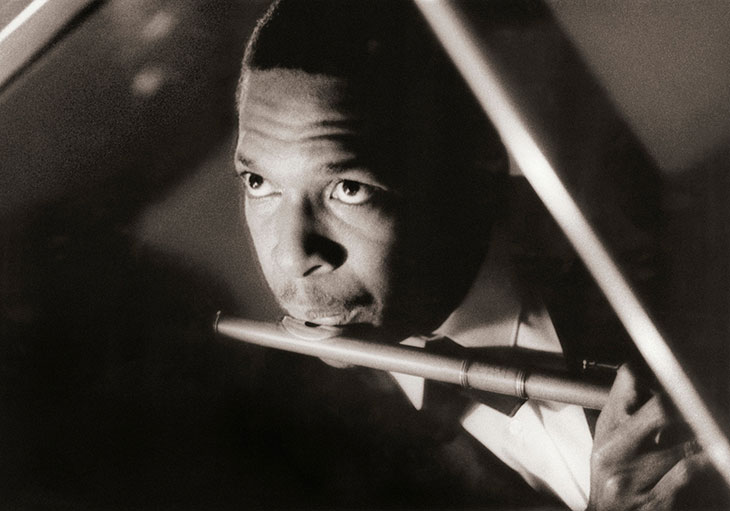

John Coltrane photographed by Robert Freeman. © The Estate of Robert Freeman

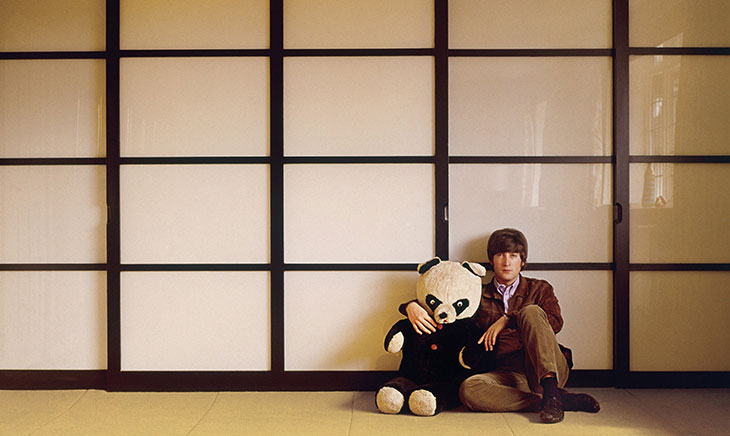

The archive stretched back to Freeman’s work in the early 1960s for the Sunday Times, where he made his name shooting portraits – from Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev to jazz greats such as Dizzy Gillespie and John Coltrane. His moody monochrome shots of the saxophonist – bebop was rather more to Freeman’s musical taste than pop music – subsequently brought him to the attention of Brian Epstein, manager of a Liverpudlian four-piece who were at that time storming the ‘hit parade’. In short order, Freeman became the Beatles’ most trusted photographer; he travelled with them on tour, discussing music and sharing a room with John Lennon, and was the go-to man for their album-cover portraits.

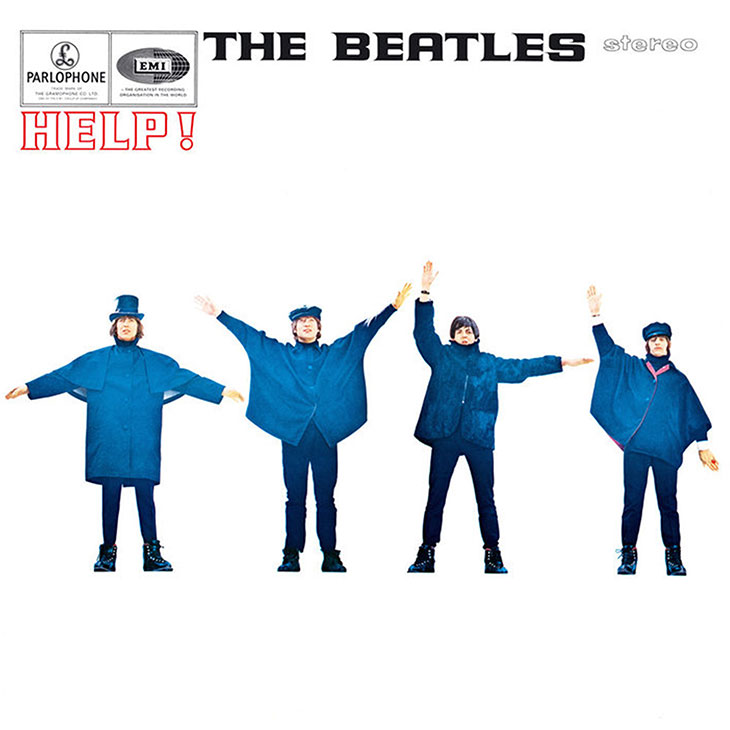

These were the faces that launched a million record sales, images seared into our collective memory: the chiaroscuro of half-lit faces of With the Beatles (1963), the product of an impromptu half-hour session in a hotel corridor; the playful rows of headshots of A Hard Day’s Night (1964); the graphic minimalism of the Help! soundtrack (1965), for which the quartet use semaphore signals to spell out not the album title, but the meaningless letters ‘NUJV’. Perhaps the most celebrated of all was the nascent psychedelia of Rubber Soul (1965), a woozy composition with the Beatles’ lengthening moptops tinged a mossy green, as if they were being overgrown by the foliage in the background. The warped, fish-eye effect was the product of serendipity. Freeman would habitually show his pictures to the band by projecting them on to an album-sized cardboard backdrop. ‘During his viewing session the card, which had been propped up on a small table, fell backwards, giving the photograph a “stretched” look,’ Paul McCartney later recalled. ‘Because the album was titled Rubber Soul we felt that the image fitted perfectly.’

The album cover for the Beatles’ With the Beatles (1963). © The Estate of Robert Freeman

The album cover for the Beatles’ Rubber Soul (1965). © The Estate of Robert Freeman

The album cover for the Beatles’ Help! (1965). © The Estate of Robert Freeman © The Estate of Robert Freeman

It says something about the pace at which the culture moved in the 1960s that over the course of just three years Freeman shot the covers for five of their LPs, in the process defining not only the Beatles’ image but also his own. In later life, Freeman came to feel that the idea of him as the Fab Four’s court photographer overshadowed the rest of his career – his other work included shooting the first Pirelli calendar in 1964, and a subsequent move into film direction – and that he had not been accorded the same respect as contemporaries such as David Bailey or Terry O’Neill. ‘He wanted the world to know about the rest of his works,’ says Godwin. ‘He deserves a lot more accolades.’

In his last years Freeman was incapacitated by a stroke and moved into Mary Court care home in Battersea, taking his archive with him. Nevertheless, he was determined to exhibit his works, believing that a full-scale retrospective would bring his photography the recognition it deserved. Plans were underway to donate an original print from the Hard Day’s Night sessions to the V&A, and in the very week of his death a meeting was scheduled with curators from Switzerland about a potential exhibition.

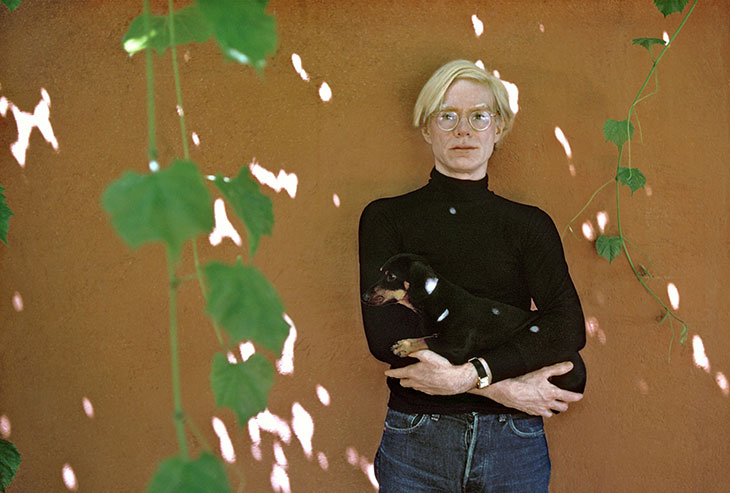

Andy Warhol photographed by Robert Freeman. © The Estate of Robert Freeman

The idea of such a retrospective is now, understandably, on hold. Over the weekend of 14–15 December 2019, little more than a month after Freeman’s death, his former home was broken into. The entire archive, from vintage prints of Muhammad Ali, Andy Warhol and Jimmy Cliff to the diaries Freeman kept on tour with the Beatles, was taken. ‘His legacy has been snuffed out,’ says Godwin. Police investigations are ongoing, but she fears that the collection may have been broken up and will resurface in shady circumstances on the art market. The Freeman estate is appealing for anybody with any information about the theft, or who may have been approached about selling Freeman’s work, to come forward. The archive, says Godwin, is effectively priceless. ‘How valuable is history?’

John Lennon photographed by Robert Freeman. © The Estate of Robert Freeman

The Freeman estate can be contacted with any information regarding the whereabouts of the archive at robertfreemanarchive@gmail.com.