It is typical of the essential shallowness of our present parliament that the current crop of MPs seems more concerned about the temporary cessation (four years, with occasional revivals) of the familiar Westminster bongs than with the clock mechanism that strikes Big Ben to make the bongs, and, more importantly, with the structure that holds both bell and clock aloft.

The great bell was cast in 1858 and hoisted up into the clock tower, which was envisaged by Sir Charles Barry but actually designed by Augustus Pugin at the end of his life. The Elizabeth Tower, as it has been renamed, now needs repair: both the clock and the tower itself. To do this properly, it is helpful, if not absolutely necessary, to stop the clock.

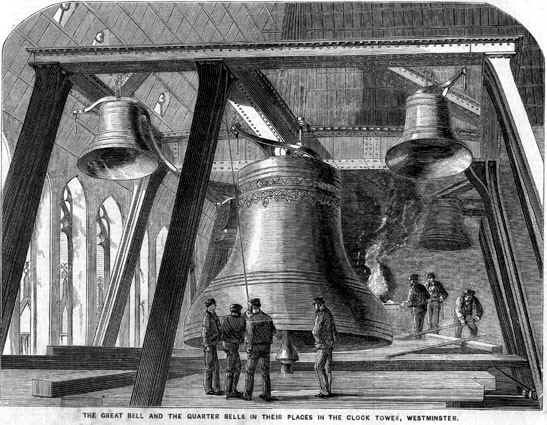

Big Ben from The Illustrated News of the World, 4 December 1858. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

But what is most important is that this restoration ought to be an immediate prelude to the repair and restoration of the whole of the New Palace of Westminster. For it needs it, desperately. After well over a century and a half, the urban, secular masterpiece of the difficult but creative partnership of Barry and Pugin needs considerable attention. The new House of Commons – designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott to replace Barry’s chamber destroyed in the German air raids of May 1941 – is awash with asbestos while its complex services need replacing.

But the House of Commons still will not commit itself to leaving the building to allow the restoration to begin. This is both selfish and financially irresponsible, for the longer the restoration is left, the further the deterioration becomes and the greater the expense of repair. Some wish for the restoration to be conducted in two phases: first the Lords’ end of the huge building, and then the Commons’ (or vice versa), but that, again, will greatly increase the cost as well as extending the duration of the restoration.

This is hardly the first time the Houses of Parliament have had to vacate their chambers: after the 1834 fire, which necessitated the Early Victorian rebuilding, the Lords were homeless for 13 years, the Commons for a further five. A century later, during the Second World War, both chambers occasionally had to use the assembly rooms in Herbert Baker’s nearby Church House while the V-1s were falling around.

This time, the period the Palace of Westminster needs to be vacated completely for restoration is six years. After expert surveys and analysis of the structure and its problems, a joint parliamentary committee has concluded that this great but now fragile public building ‘faces an impending crisis which we cannot responsibly ignore.’

Surely the Lords and Commons ought to be prepared to make this sacrifice to ensure the future of the greatest Gothic Revival building in the world, a structure – identified above all with the Elizabeth Tower – which has long been a visual symbol for London, for Great Britain and for our parliamentary democracy? As Caroline Shenton, former director of the parliamentary archives and recent historian of the building, has written, unless what is clearly necessary is done soon, ‘The Palace will either suffer a major catastrophe such as a fire similar to the one which burned down the old Houses of Parliament in 1834, or a series of cumulative smaller failures – water, gas, electricity, asbestos, stonework, sewerage – which will bring the infrastructure of the Palace to a standstill, or cause irreparable damage to Charles Barry and AWN Pugin’s masterpiece.’

The trouble is that six years is longer than a maximum parliamentary term, so a whole intake of MPs might be denied the pleasure and privilege of using and working in this great building. And it is the building – the glorious Gothic interiors created by Barry, Pugin and, later, Scott – that gives them any sort of stature and glamour. Without the setting of the Palace of Westminster, many of them clearly fear that they will appear as the drab mediocrities that most of them are. And they are right. But the New Palace of Westminster doesn’t just belong to them: it belongs to all of us.

It is for the whole nation, therefore, that the restoration should go ahead as soon as possible. ‘… Send not to know / For whom the bell tolls…’ It needs to stop tolling awhile for its own sake and for the sake of the great building which houses our ailing, selfish parliament.

Lead image: used under Creative Commons licence [CC BY 2.0])

Big Ben is the least of the Palace of Westminster’s problems

Palace of Westminster, London. Photo: Tony Moorey/Flickr (Creative Commons)

Share

It is typical of the essential shallowness of our present parliament that the current crop of MPs seems more concerned about the temporary cessation (four years, with occasional revivals) of the familiar Westminster bongs than with the clock mechanism that strikes Big Ben to make the bongs, and, more importantly, with the structure that holds both bell and clock aloft.

The great bell was cast in 1858 and hoisted up into the clock tower, which was envisaged by Sir Charles Barry but actually designed by Augustus Pugin at the end of his life. The Elizabeth Tower, as it has been renamed, now needs repair: both the clock and the tower itself. To do this properly, it is helpful, if not absolutely necessary, to stop the clock.

Big Ben from The Illustrated News of the World, 4 December 1858. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

But what is most important is that this restoration ought to be an immediate prelude to the repair and restoration of the whole of the New Palace of Westminster. For it needs it, desperately. After well over a century and a half, the urban, secular masterpiece of the difficult but creative partnership of Barry and Pugin needs considerable attention. The new House of Commons – designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott to replace Barry’s chamber destroyed in the German air raids of May 1941 – is awash with asbestos while its complex services need replacing.

But the House of Commons still will not commit itself to leaving the building to allow the restoration to begin. This is both selfish and financially irresponsible, for the longer the restoration is left, the further the deterioration becomes and the greater the expense of repair. Some wish for the restoration to be conducted in two phases: first the Lords’ end of the huge building, and then the Commons’ (or vice versa), but that, again, will greatly increase the cost as well as extending the duration of the restoration.

This is hardly the first time the Houses of Parliament have had to vacate their chambers: after the 1834 fire, which necessitated the Early Victorian rebuilding, the Lords were homeless for 13 years, the Commons for a further five. A century later, during the Second World War, both chambers occasionally had to use the assembly rooms in Herbert Baker’s nearby Church House while the V-1s were falling around.

This time, the period the Palace of Westminster needs to be vacated completely for restoration is six years. After expert surveys and analysis of the structure and its problems, a joint parliamentary committee has concluded that this great but now fragile public building ‘faces an impending crisis which we cannot responsibly ignore.’

Surely the Lords and Commons ought to be prepared to make this sacrifice to ensure the future of the greatest Gothic Revival building in the world, a structure – identified above all with the Elizabeth Tower – which has long been a visual symbol for London, for Great Britain and for our parliamentary democracy? As Caroline Shenton, former director of the parliamentary archives and recent historian of the building, has written, unless what is clearly necessary is done soon, ‘The Palace will either suffer a major catastrophe such as a fire similar to the one which burned down the old Houses of Parliament in 1834, or a series of cumulative smaller failures – water, gas, electricity, asbestos, stonework, sewerage – which will bring the infrastructure of the Palace to a standstill, or cause irreparable damage to Charles Barry and AWN Pugin’s masterpiece.’

The trouble is that six years is longer than a maximum parliamentary term, so a whole intake of MPs might be denied the pleasure and privilege of using and working in this great building. And it is the building – the glorious Gothic interiors created by Barry, Pugin and, later, Scott – that gives them any sort of stature and glamour. Without the setting of the Palace of Westminster, many of them clearly fear that they will appear as the drab mediocrities that most of them are. And they are right. But the New Palace of Westminster doesn’t just belong to them: it belongs to all of us.

It is for the whole nation, therefore, that the restoration should go ahead as soon as possible. ‘… Send not to know / For whom the bell tolls…’ It needs to stop tolling awhile for its own sake and for the sake of the great building which houses our ailing, selfish parliament.

Lead image: used under Creative Commons licence [CC BY 2.0])

Share

Recommended for you

Cultural engineering in Norman Sicily

The island’s Norman rulers encouraged the use of Islamic, Byzantine, and Romanesque elements in art and architecture as a deliberate display of their power

Studying art history can make you famous – honest!

Studying art history can turn you into an art historian. Or it can make you famous, it turns out.

Staring at the zeitgeist

August Sander’s photographs and Otto Dix’s paintings take an unflinching look at Weimar Germany