One lesson to be learned from studying artists’ depictions of Britain’s changing landscape is that our cherished opinions about the proper content of the scenic view are always conditioned by historical prejudice. Eyesores, like beauty, are properly attributed to the beholder. In our own time, the wind turbine excites passions across the political spectrum, from the Campaign for the Protection of Rural Wales (which has opposed the installation of turbines on Anglesey) to Donald Trump – who complained that the installation of an offshore wind farm in view of his Aberdeenshire golf course would be a ‘disaster’ comparable to the Lockerbie bombing. Such protests are never quite as straightforward as they seem. Anglesey, for instance, is proud host to some 49 windmills of the old sort, located there for precisely the same climatic reasons that the island is now a prime site for the generation of renewable energy. The sudden interest shown by the Trump Organization in the preservation of the ‘bucolic Aberdeen bay’ might be thought to sit uncomfortably alongside Mr Trump’s own enthusiasm for that notably artificial achievement of landscape engineering: the golf course. In June last year it emerged that the dunes at the Foveran Links, on which the Trump International course sits, were in such poor condition that Scottish National Heritage was considering removing them from its list of Sites of Special Scientific Interest.

The windmill has no a priori claim to greater naturalness or beauty than the turbine; the scooped bunkers and buzz-cut greens of a golf course present, in themselves, no less artificial or more pleasant a prospect than the spinning blades of a coastal wind farm. There may be other factors to consider with respect to the impact of such constructions on local ecosystems, but from the point of view of aesthetics these contemporary controversies remind us that the depiction of landscape in works of art has always served not only to represent but to create our ideas of natural beauty.

At the end of the 18th century, when William Gilpin was first instructing British artists and travellers in the enjoyment of the ‘picturesque’, the windmill was an object of sufficient antiquity to seem, if not a natural feature, at least an integral part of the rural scene. So too, the roads and tracks upon which he travelled appeared to him products less of labour and maintenance than of time and chance, the wilder sort serving as ‘no bad substitute’ for ‘the mazy course of a river’. But there was one new interloper which proved incompatible with Gilpin’s preconceptions about the proper contents of the rural landscape: a technological artefact made possible and necessary by the implacable forces of economic development, suddenly imposed without proper consultation on the unsuspecting inhabitants of the countryside. This precursor of the wind farm, the pylon, the mobile-phone mast, so inimical to Gilpin’s sense of the picturesque, was the canal.

The canal as artistic subject had precedents in popular views of Venice by artists such as Bernardo Canal, and his more famous son Giovanni Antonio, better known by his nickname, the ‘little Canal’ – or Canaletto. But it took time for artists and connoisseurs to accept as appropriate subjects for painting the new canals which had begun to traverse the British landscape. Travelling in the area around Cannock Chase in 1772, Gilpin reported, in his Observations on Several Parts of England, that the area was ‘rich and woody’ but ‘disfigured by a new canal, which cuts it in pieces’. A river taking its natural course, he went on, was ‘one of the most beautiful objects in nature’, but a canal – ‘one of these cuts, as they are called’ – was something quite new, and abominable:

Its lineal, and angular course – its relinquishing the declivities of the country; and passing over hill, and dale; sometimes banked up on one side, and sometimes on both – its sharp, parallel edges, naked, and unadorned – all contribute to place it in the strongest contrast with the river. An object, disgusting in itself, is still more so, when it reminds you, by some distant resemblance, of something beautiful.

The Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal, opened in the year of Gilpin’s travels, was the brainchild of the great English canal engineer James Brindley. Brindley had made his reputation as consultant to the Duke of Bridgewater during the construction of the Bridgewater Canal, an undertaking which had drastically increased the flow of coal from mines under the Duke’s estate at Worsley to market in Manchester, kick-started the canal-building boom of the late 18th century, and helped to fuel – literally – the early decades of the Industrial Revolution.

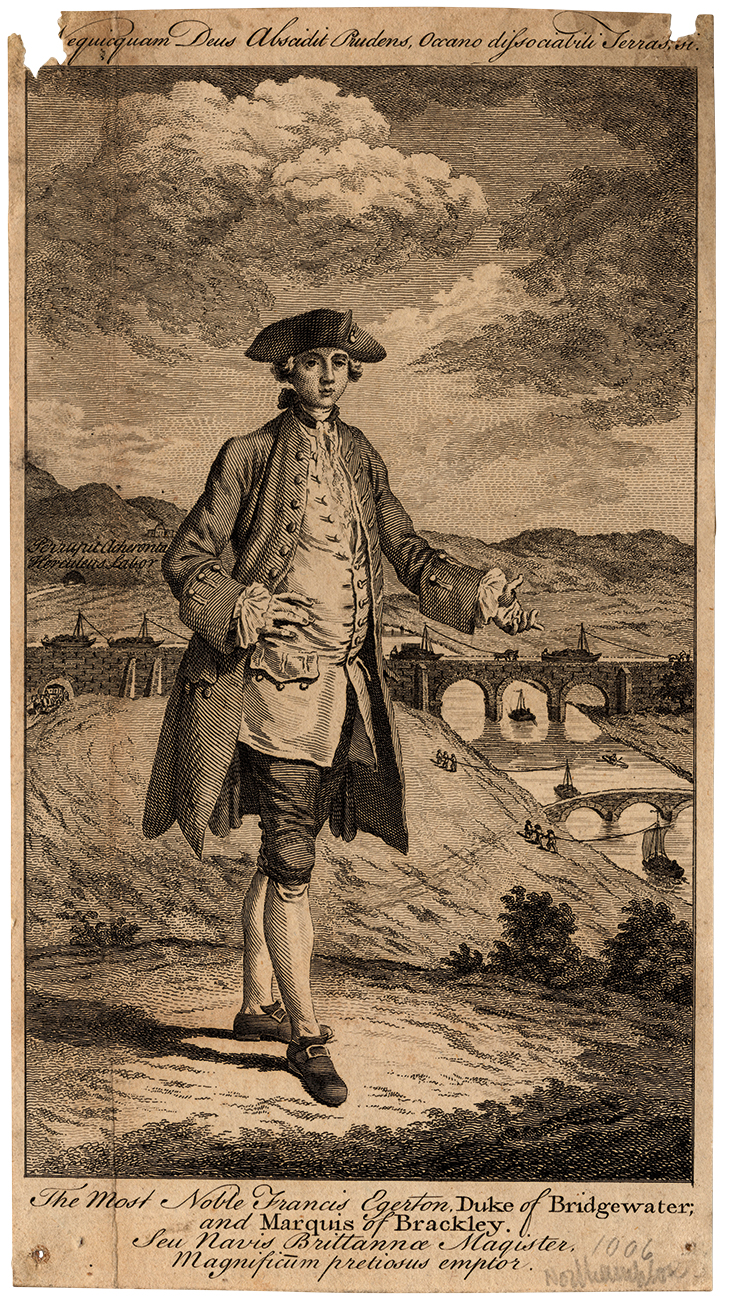

Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater (1766), after unknown artist. National Portrait Gallery, London

An engraving from 1766 shows a full-length portrait of the Duke, but the focus of the image, to which his gesture directs the viewer, is the canal itself, and more particularly its most notable feat of engineering, the triple-arch crossing at the village of Barton which carried the canal across the river Irwell on Britain’s first navigable aqueduct. In this image, made at a time when artists such as Thomas Gainsborough were refining the style of early British landscape painting, the mediation of the Duke is necessary to justify the depiction of the modern engineering marvel. By the early 1790s, however, the scene could stand on its own merits as the subject of a watercolour drawing by G.F. Yates, now in the collection of the Science Museum. Unlike pylons or wind farms, canals were readily naturalised as appropriate components of the picturesque landscape precisely because the years of the first canal boom (between the 1760s and the 1830s) coincided with the rising popularity in Britain of landscape painting itself.

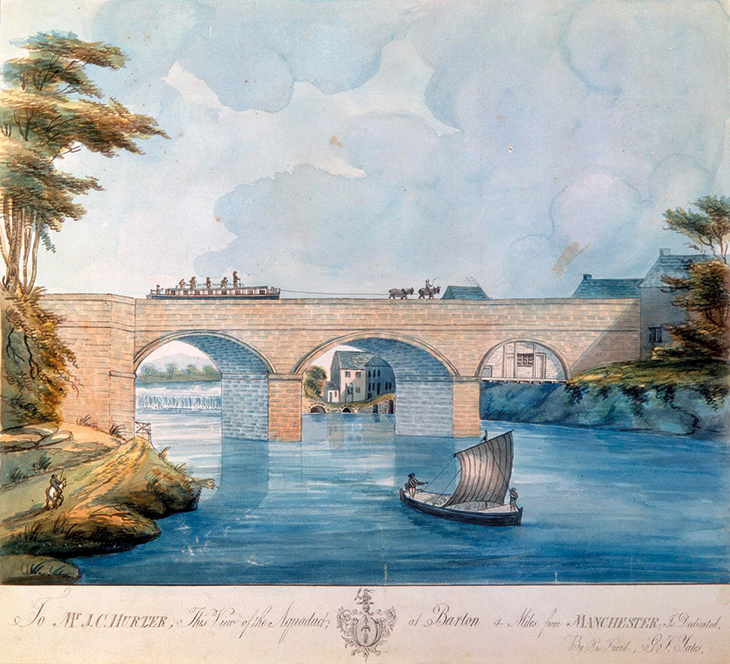

The Aqueduct at Barton (c. 1793), G.F. Yates. Photo: © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, London

Yates’s scenic view focuses attention on two points which explain how canal scenes helped to influence the direction of British landscape painting in its formative years, as well as in its later history. Such pictures clearly direct us, firstly, to the canal as a place where the rhythms of life are being reorganised by means of the engineer’s technical know-how and the capital of the new canal companies, and, secondly, to the landscape as a place of economic activity – particularly the labour of ordinary workers. One reason that canals and canalised rivers drove the expansion of commerce in late 18th- and early 19th-century Britain was that they were far less vulnerable than natural waterways to the vagaries of the weather and the seasons. Hauliers no longer had to contend with adverse currents or depend upon the wind to drive their barges. From the early 19th century, fast ‘fly-boats’ worked nonstop on Britain’s busy canal network, hauled by relays of horses and men. And while the necessity of moving through locks meant that canal traffic moved slightly slower than traffic by road, the canal boats could haul far larger tonnages, and were less likely to be held up by mud, ice, or snow.

The cultural historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch has described how, in the 1840s, Britain’s railway companies began to ‘standardise’ time around the country in accordance with their schedules, but that standardising process had already begun in the early years of the century, albeit on a local scale, when some canal companies began to introduce timetables for passengers and goods. Already in Yates’s watercolour one can see the interaction of different temporalities: the river barge under full sail downstream, driven on by wind and current; the horseman making his way along a rutted and precarious bankside track; and the stately canal-boat moving steadily across the picture, held aloft by the geometrical perfection of the Barton aqueduct. In canal paintings of this period, the landscape is not simply an idealised natural scene to be lingered over and taken in: rather, it has become a fully inhabited and developed place, a zone of transit for bargees en route from field or mine to market, a space wrested from nature by engineer and dredging team, maintained and controlled by a vigilant lock-keeper.

The Lock (1824), John Constable. Image courtesy Christie’s

In Constable’s scenes of the canalised River Stour, for instance, all is in motion. Heaving the windlass to open the sluices which will let down the barge into the lower river, the sinewy lock-keeper in The Lock (1824) is the painter’s collaborator in the art of composing landscapes. His stationary labour makes the painting’s motion possible, so much so that Constable would return to the same subject two years later in A Boat Passing a Lock (1826). The latter painting widens the view so that we see further up river to the far lock-gates: this is now landscape painting in format as well as subject. The keeper, hatless, is just beginning to wind the mechanism; the dog peeking from the far bank in the earlier painting has crossed over to the near side. So too, in The Leaping Horse (1825) – another of the Stour paintings – everyone is on the way to somewhere else: the bargees pushing off and raising a sail; the horse caught mid-leap. ‘It is a canal,’ Constable wrote to his friend John Fisher, ‘and full of the bustle incident to such a scene’. The bustle was the important point: these are neither stately aristocrats calling our attention to their control of land and capital, nor idle pleasure seekers admiring the landscape on our behalf, but ordinary people (and animals) going about their daily lives.

By connecting distant places, facilitating commerce, and introducing new forms of labour and leisure, the canal boom intervened in the temporality of everyday life both in the British countryside and in cities. In A Panorama of Nottingham from the Canal, a work from the school of Paul Sandby, the canal is a space of leisure as well as labour. A well-dressed fishing party gathers on the near bank, while in the middle distance a group of industrious eelers spread their long cylindrical nets out on the grass. Castle and church preside over the scene, but the canal and its bustling marina serve as gateway to the city, a place where urban and rural forms of life meet. The canal paintings of Constable and his peers helped to shape the British picturesque by depicting the arteries of commerce which bound together the citizens of an industrious nation.

The architectural drawings of Thomas Hosmer Shepherd survey the Regent’s Canal, which opened in 1820, as a well-established part of London’s industrial landscape. Lock-keepers wind the mechanism controlling the flow of water through the gate paddles, and loaded barges float their cargo past the looming chimney-stacks of a gasworks where barge-hauled coal is transformed into the gas now flowing into the street-lamps and domestic lights of the capital. The association in visual art between canals and the working people who undertook their construction and facilitated their burgeoning trade remained strong, and in some way explains the distaste felt by the well-to-do councillors of Manchester towards Ford Madox Brown’s historical mural The Opening of the Bridgewater Canal, AD 1761 on its installation in their Town Hall in 1892.

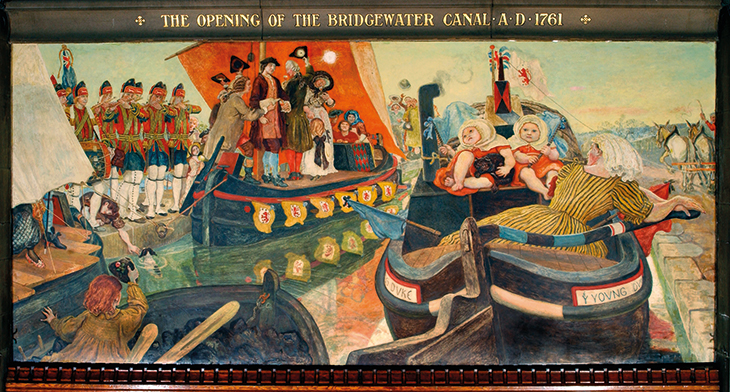

The Opening of the Bridgewater Canal, AD 1761 (1892), Ford Madox Brown. Manchester Town Hall/Bridgeman Images

Unaccustomed to the carnival atmosphere, Brown’s Duke of Bridgewater looks as if he has had to be lashed to the mast, like some Georgian Odysseus, lest he pitch into the water accompanied by the siren strains of the pipe band. Brindley, the engineer, is the obliging figure who confirms his status as master of all liquid media by leaning forward to supply the Duke and his guests with brandy for an inaugural toast. Besides him, the whole landlubbing estate party, awkwardly perched on their old-fashioned barge-cum-longboat, have been upstaged by the ruddy-complexioned bargewoman in the foreground, who like her chubby children seems comfortable on the water, swaying naturally with the movement of this suspiciously modern-looking vessel. The people who matter in Brown’s painting are not the Duke contemplating his higher revenues, nor the burghers of Manchester seeking the adornment of painting for their civic offices, but the mass of people who haul the coal and tend the children, and who here invade both the historical scene and the walls of the Town Hall to remind their masters where their wealth comes from.

By the second half of the 19th century, however, the canals of Britain had come to be seen in a different light. A large part of the traffic and investment which had sustained the canal network had been diverted to the booming railways; many formerly busy canals had themselves been converted to rail routes. The decline continued long into the 20th century. On the one hand, the canal was once again associated with pastoral simplicity, as in the paintings of David Bomberg, who during the First World War had served as an army messenger riding the towpaths of Flanders. Bomberg’s post-war studies of barge families – including Bargee (Mother and Child) (1921) and the striking Barges (1919) – depict figures cast adrift from the rest of society, eking out a poor but dignified living on the waterways. On the other hand, the canal increasingly came to represent poverty, spiritual alienation, and social decay.

Barges (1919), David Bomberg. © Tate

In the third section of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922), for instance, the riparian love poetry of Spenser’s Elizabethan England (‘Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song’) degrades into the modern malaise of a figure ‘…fishing in the dull canal / On a winter evening round behind the gashouse’. The reek of gashouses and other industrial pollutants also drift through Cecil Day-Lewis’s 1935 reworking of Marlowe’s ‘The Passionate Shepherd to His Love’, evoking the grimy waterways of modern Dublin: ‘At evening by the sour canals / We’ll hope to hear some madrigals’. And in post-war Salford, the playwright and folk singer Ewan MacColl smelt the same stink: ‘I met my love by the gasworks croft, / Dreamed a dream by the old canal, / Kissed my girl by the factory wall, / Dirty old town…’

The Towpath (1912), C.R.W. Nevinson. Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford

Such are the desolate spaces evoked in the interwar paintings of Algernon Newton, whose deserted towpaths and overgrown wharves earned him the tautologous nickname ‘the Canaletto of the canals’. Newton’s paintings register the canal as an important site within the iconography of what we might call the post-industrial picturesque: that mode or genre in which the peaceful landscapes of the early picturesque return, transfigured into the empty lots and barren zones of the modern city. Dirty and deserted, the canal becomes a place for drifters and outcasts such as the barge-hand Joe in Alexander Trocchi’s novel Young Adam (1954), and the courting couples Joe watches congregating on shore: ‘Perhaps it is the water that attracts them as much as the seclusion, and of course the danger.’ The dangerous, decadent canalside becomes an ironic substitute for the riverbank as the courting place of choice for young working-class lovers like the couple caught mid-clinch in C.R.W. Nevinson’s atmospheric The Towpath (1912). As in Trocchi’s novel, their twilight embrace seems to hold in it the hint of something more sinister, a picture less of passion than of submission. Or consider the louche cigarette-smoking man perched on a bridge railing in Stephen Bone’s Little Venice (1952), no doubt waiting for a rendezvous as he casually observes the laundry drying on a barge, the swooping gull, the pair of children with a net; all of them, one imagines, optimistic about their chances of making a catch even in these unpromising waters.

By the Canal (1976), Prunella Clough.

From mid century onwards, however, the long deterioration of the canal system was slowly and systematically reversed, thanks largely to the efforts of the Inland Waterways Association, founded after the Second World War by the writers Robert Aickman and L.T.C. Rolt, and the publisher Charles Hadfield – later to become the preeminent historian of the British canal network. In the absence of heavy industry, the canals became once again a place of pleasure and respite. For some artists, the canal remained a place of grime and decay, a no-go zone captured in the rusty tones and wiry barbs of Prunella Clough’s post-industrial abstract By the Canal (1976). But by then some canals, at least, were beginning to benefit from extensive restoration projects, and a growing nostalgic interest in the pleasures of slow travel. In Julian Trevelyan’s prints of the 1970s, relaxed figures steer narrowboats through pastoral landscapes, or recline languidly on the roofs of barges passing through urban locks, while Derrick Greaves’s Canal (1997) presents a more playful alternative to Clough’s abstraction, juxtaposing the straight edges of the canal cut with the softer organic forms of bankside foliage.

The story of canal painting in Britain is an important part of the story of landscape painting itself. By tracing its history, we can see how social and technological developments have shaped the nation along with the art which depicts its landscapes. From the late 18th century, when the excavation of artificial cuts began to transform the appearance of the British countryside to meet the needs of commerce and industry, to the productive tension between everyday realism and abstract forms characteristic of British modernism, the human-made landscape of the canal clarifies the close relationship between nature and artifice, and demonstrates how the unfamiliar forms of a new technological era can become, over time, part of the scenery.

From the January 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze