Carole Gibbons’s show at Hales Gallery, ‘Of Silence and Slow Time’, takes its title from the opening of Keats’s ‘Ode to a Grecian Urn’: ‘Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness, / Thou foster-child of silence and slow time’. The phrase is apt in a number of ways. Silence and slow time are the atmospheric conditions in which these nine paintings – produced between 1974 and 1987 – emerged. Predominantly still lifes, heavily worked-at, their long gestation is visible in the layering of paint.

In subject and setting, the paintings evoke the slow time of domesticity and parenting, a state perhaps akin to what psychoanalyst Lisa Baraitser calls the ‘durational drag of staying alongside others’. (Many of them were produced while Gibbons raised her son, the painter Henry Gibbons Guy, in the Glasgow flat where she still lives and works.) And ‘slow time’ can also be seen as obliquely descriptive of Gibbons’s own belated emergence. Until very recently, her last major solo show had been in 1975. This past year, however, has seen Gibbons – who is 88 – exhibit at White Columns in New York, while last year saw the publication of a first monograph. Hers is an artistic career that has run to a different clock. Perhaps the closest parallel for her recent success would be the late recognition of Alice Neel.

Green Moroccan Vase (c. 1982), Carole Gibbons. Photo: Damian Griffiths; © Carole Gibbons

Slow time is also part of the response many of these paintings anticipate and mediate. While there are moments of sharpness and clarity – such as the flowers in Cornflowers, Shell, Stone Head (1974) – it often takes a while for her pictorial spaces to come into focus. Background objects are often so obscurely rendered that it seems as if they’re semi-dissolved in some digestive solution: in Green Moroccan Vase (c. 1982), it’s only the titular object that stands out intelligibly from the dark brown and purple masses that make up most of the painting. There are traces of Vuillard, Bonnard and Cézanne in this aspect of her work. What makes it fresh is when it is occasionally and unexpectedly electrified by the feyness of Chagall, the weirdness of Kitaj. The combination of domesticity and fantasy, precision and murkiness, the quotidian and the oneiric, makes Gibbons’s work feel carefully balanced, but unpredictable.

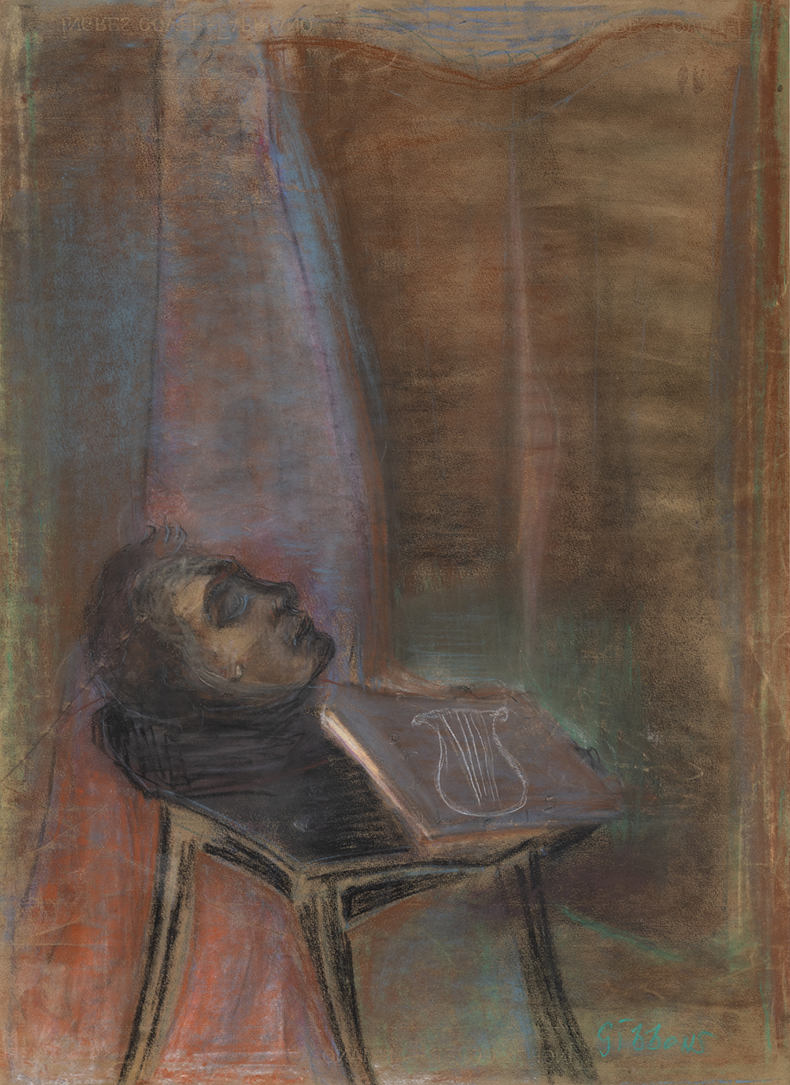

Orpheus (c. 1980), Carole Gibbons. Photo: Damian Griffiths; © Carole Gibbons

Gibbons is a literary painter; in her rich and inventive domestic modernism, I’m reminded of the New York School poets Bernadette Mayer and Alice Notley. Like these poets, Gibbons brings out the latent aesthetic potential of the home, but complicates it through strategic anachronism. She does this in part through classical citations, evident most explicitly here in the haunting pastel Orpheus (c. 1980). The head (or Keatsian death-mask) of a poet lies propped on the surface of a woozily swaying table, against a backdrop of billowing curtains. It’s a solemn, even melodramatic image, but its effect is powerful.

Chair, Flower and Bottle (c. 1985–87), Carole Gibbons. Photo: Damian Griffiths; © Carole Gibbons

The most recent piece here, Chair, Flower and Bottle (c. 1985–87), stands out as an anomaly. The palette – ecstatic day-glo pinks, blues and oranges – is distinct from everything else displayed. Andrew Cranston, in a recent essay, describes this part of her visual vocabulary as ‘sorbet-sweet’. Risking prettiness, even kitsch, it’s a daring break from the subtler tones of her earlier work, creating a conflict between the silent and slow occasion of the painting, and the garrulous vibrancy of its colours. The effect is amazing.

Chinese Horse (c. 1977), Carole Gibbons. Photo: Damian Griffiths; © Carole Gibbons

Yet seen alongside the earlier pieces collected here, the continuities as well as the disjunctions start to make themselves felt. In the luminous Chinese Horse (c. 1977), the eponymous toy-object emerges from a dark smudgy background as a ventilating streak of jade. This radiant, nearly-too-much palette is a key mode in which Gibbons has worked during the past 40 years, and it’s thrilling to see it represented here both in germinal form and fully elaborated. This group of paintings demonstrates Gibbons’s extraordinary range and facility as a colourist. It also shows how she discovered – independently, and on her own terms – that domestic space can be a setting for quietly radical aesthetic production.

‘Carole Gibbons: Of Silence and Slow Time’ is at Hales Gallery, London, until 13 July.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)