In 1906, when the philanthropist Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919) promised his art collection to the government-run Smithsonian Institution in Washington, the gift came with some tight strings. To this day, the staff at the gallery that he founded as the Smithsonian campus’s first art museum cannot borrow or lend anything, and they can buy works only in certain categories that he dictated. Freer wanted to preserve evidence of his own scholarly interests and visual appetites, which ranged from ancient Egyptian glass mosaic chips and iridescent Syrian ceramic bowls to Whistler’s abstract paintings of befogged riverbanks. Freer had travelled the world on acquisition binges, financed by his railroad-car manufacturing fortune, and he hoped that the multicultural objects on permanent display would help the masses experience what he called ‘freshness of vision’.

The Freer Gallery of Art, which is especially renowned for its Asian holdings, has been closed for nearly two years while undergoing its second major renovation (the first was in 1993). Experts have refreshed everything from the skirting boards to the gallery podcasts. When the building reopens on 14 October, new shows will focus on historical precedents for contemporary concerns, whether strivings for affordable mass-production, longings for solace in nature, or fears of apocalyptic government collapse. The staff has also brought out paintings, sculpture, and archival materials that shed light on the enigmatic Freer.

For all the reams of correspondence and inventories that Freer kept neatly filed away, he remains ‘a little bit mysterious,’ says Julian Raby, the director of the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art and adjacent Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (a 1987 annex that technically has a separate collection and is free to lend and borrow). The compound, with integrated staff, focuses on Asian art and is known in shorthand as the Freer|Sackler.

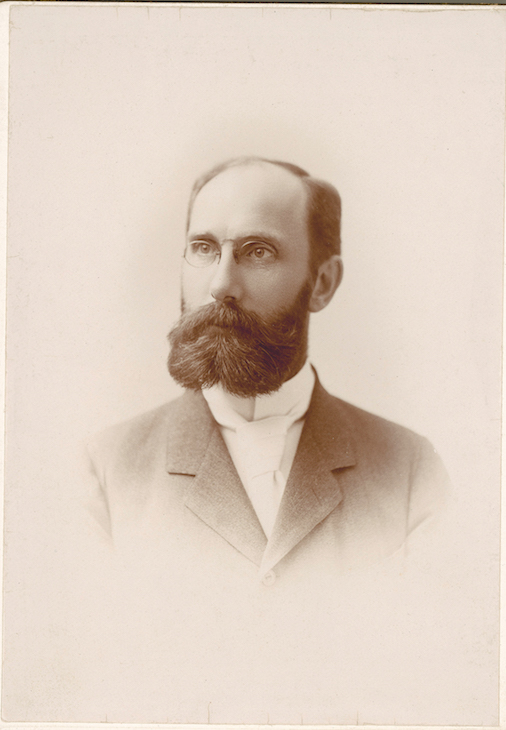

A number of other American museum founders of the Gilded Age imposed unusual rules on the future stewards of their collections. Isabella Stewart Gardner, for instance, dictated that objects in her Boston galleries could scarcely be moved. Freer, who died four years before his treasures went on view in 1923, is perhaps the least-known member of the elite benefactor group. Although he did enjoy newspaper attention and politicians’ gratitude for his generosity and erudition, he largely avoided the limelight and society parties. And he did not record his inner life, as Lee Glazer, the Freer’s curator of American art, writes in a new book published as part of the reopening celebrations, Charles Lang Freer: A Cosmopolitan Life. Whenever he came close to confessing something emotionally revealing in his letters, he would interrupt himself with an offhand phrase like ‘But enough of personality!’

Glazer explores Freer’s humble origins in Kingston, New York, on the Hudson River’s west bank about 85 miles north of Manhattan. Freer dropped out of his hometown school after eighth grade, around the time that his mother Phoebe died and his father Jacob’s health began to fail. Jacob, who suffered from syphilis, had futilely pursued careers as jockey, stable owner and innkeeper. Freer’s first jobs included stints as a cement factory worker, store clerk, and railroad accountant. Glazer describes him as ‘disciplined, meticulous, circumspect, and hard-working’. By his twenties, he had partnered with Frank J. Hecker, a railroad-car manufacturing executive, to create a factory in Detroit that dominated the industry.

On their 80-acre complex, 5,000 men laboured in freight-train production lines. The young capitalist Freer focused on the bottom line through 1880s economic booms and 1890s financial crises, and at times he ‘ignored the suffering of workers’, Glazer observes. When a Polish immigrant foundry employee was killed in a coal car accident, Freer wrote to Hecker that $25 would easily compensate the grieving survivors of the ‘Polander of the lowest type’. By 1899, Freer had helped engineer the merger of his company with a dozen other railroad-car makers and pocketed enough profit to devote the rest of his life to what he described as ‘active idleness’.

He started collecting ‘with the same methodical care he applied to his business endeavors,’ Glazer writes. His early shopping interests included self-help books, poetry compendiums and relatively staid artworks by contemporary Europeans including Henri Fantin-Latour. Among his first adventurous purchases was a group of two dozen Whistler etchings known as the Second Venice Set. It depicts Venice from unconventional angles – ‘back canals, obscure buildings, and shadowy doorways’, as Glazer puts it. Freer eventually amassed over 1,000 works by Whistler plus the glittery Peacock Room that Whistler had originally installed at the shipping magnate Frederick Leyland’s townhouse in London. Freer managed to remain friendly with the famously litigious and impractical artist, who shuttled between London and Paris, while also supporting a few now-obscure painters in America. Freer invited his favourites to line his Detroit mansion with portraits and landscape paintings. The circle included Dwight William Tryon, a Smith College professor known for views of unpopulated flat tree groves, and Abbott Handerson Thayer, a manic depressive whose subject matter ranged from New Hampshire mountains to flamingoes and angels. Freer further expanded his cultivated network by joining men’s clubs, and at times he helped foster his fellow members’ salacious behavior. ‘Be a little careful how you write,’ the painter Thomas Wilmer Dewing warned the architect and tastemaker Stanford White, when the two men were comparing notes about erotic performances in Paris that Freer had organised.

Despite constant bouts of ill health (officially attributed to neurasthenia, which Glazer calls ‘a privilege of wealth’, but also caused by incurable syphilis), Freer spent years on the road. He hiked mountains in the Catskills and Japan, clambered around Egyptian temple ruins and ventured deep into Buddhist caves in China. At Freer’s villa in Capri, known as the Abode of the Idlers, guests wore costumes in a procession modelled after ancient Persian religious rites. Wherever he went, he met, bargained with and learned from dealers. In Paris, Siegfried Bing supplied him with Japanese scrolls and Persian ceramics; he acquired Chinese jades from C.T. Loo, who became a controversial figure while stripping archaeological sites. Freer collected souvenir living animals, too; he sent Thayer a present of prairie dogs, and Freer’s gift of a songbird from Calcutta comforted Whistler’s wife Beatrice in her last days. When Freer found out that some forged antiquities had crept into his massive inventory, he was unfazed. They would be useful to future researchers, he predicted; he called them ‘educational thorns that helped others’.

By 1905, as he formulated plans for what he preliminarily called ‘the Washington building’, his celebrity friends included the inventor Alexander Graham Bell, a Smithsonian board member, and President Theodore Roosevelt. The Smithsonian board unanimously accepted his gift. Roosevelt telegrammed to report ‘how pleased I am at what has been done’; he was eager to set up the new galleries partly to foster better diplomatic ties with Asian countries that resisted American influence. Freer pondered the design while analysing older museums in Europe, criss-crossing the Continent; he wanted to avoid those institutions’ ‘pretentiousness, confusion and ugliness’, he told Hecker. He eventually collaborated with the New York architect Charles Platt to create an Italian Renaissance rectangle of marble and granite.

The enfilades are lit by skylights and overlook a hedge-trimmed courtyard with a fountain, where Freer hoped the public would find peaceful time to process their ‘emotional reactions’ to the art. He lived long enough to specify oak benches and glossy dark floors for the uncluttered galleries. The original layouts and palette, Raby says, ‘had almost a stark minimalism’, and they allowed ‘a sense of privilege for the artefacts’.

Freer’s will ensured that his 1,500 American works would remain an unchanged time capsule. ‘He closed the door on anything that came after,’ Glazer says. But he did allow curators to make ‘occasional purchases’ of Asian and Middle Eastern objects that ranked as ‘very fine examples’. Since his death, some 17,000 acquisitions of antiquities have been folded into his original trove of 9,500 pieces. The Sackler’s holdings – which include contemporary works, such as Gauri Gill’s haunting portraits of villagers in India and Tarek al-Ghoussein’s images of modern Kuwaiti buildings in ruins – bring the total count onsite to 41,000.

Over the years, the staff maintained much of Freer’s intended décor in the galleries, but blandness and obsolescence crept in that muddied the founder’s vision. Dark skirting boards ended up whitewashed; matte grey carpets were laid over the floors. Climate control equipment and other mechanicals relied on what Raby calls ‘a very ancient system’. Visitors longed for more guideposts, in the form of signage, high-tech audiovisuals and clear narratives.

Less than two years of closure for the renovations has apparently proved a bit of a frazzling fast-track deadline. ‘Freer not’ was a confidence-building slogan posted in a staff office corridor when Raby gave me a tour of the nearly completed building late this summer. We snaked our way through basement caverns full of new tanks, ducts and gauges that control temperature and humidity, led by in-house project manager Richard Skinner. In the galleries (there are 20 exhibition spaces in total), planes of terrazzo flooring had been newly exposed and trimmed with Belgian quartz skirting boards in charcoal shades. Floor-to-ceiling banners were being hung in the corridors to identify galleries, replacing tiny wayfinding panels. A polychromed wood temple guardian, carved in Japan around 800 years ago and depicted stomping on a demon, was reflected in the terrazzo. The subtle mirroring of objects underfoot, Raby says, ‘actually creates a sense of visual acuity’.

The Asian and Middle Eastern art displays (with redesigns overseen by staff member Karen Sasaki) now emphasise modern resonances. In the 13th century, as the curators explain via podcasts and wall texts, threats of bloody Mongol invasions convinced some Japanese that their nation and culture were doomed – just as some destructive contemporary politicians are causing widespread fears of systemic collapse. Captions for ancient Chinese bronze vessels and bells note that standardised components were used in mass production, foreshadowing China’s current status as home to the world’s greatest concentration of assembly lines.

The Freer has always attracted a large number of first-time visitors; new arrivals on any given day may even include moon-landing aficionados, who have wandered in out of curiosity after touring the Smithsonian’s nearby National Air and Space Museum. Massumeh Farhad, the Freer|Sackler’s chief curator, says one goal of the redisplays is to reassure the public that, like Freer, ‘you don’t need to be an expert’ to relate to varied masterworks. And the content can be easily updated, even without borrowing or lending anything. ‘We’ve banned the phrase “permanent galleries”,’ Raby says.

The Sackler wing’s autumn shows focus on, among other topics, ancient Egyptian cat deity sculptures (borrowed from the Brooklyn Museum) and an 8th-century Buddhist monk’s pilgrimage along the Silk Road that encompassed temples and caves that Freer visited, too. And for the first time, a gallery within the Freer building will be devoted to his open-minded approach. The objects will vary from Whistler’s art to Japanese lacquer boxes and Raqqa vessels made in Syria. Autochromes that Alvin Langdon Coburn took in 1909 show the railroad magnate posing with depictions of women in dream states by Whistler, alongside a Raqqa jar and Egyptian bronze figures of Anubis and Neith.

The compound keeps busily acquiring. Among the purchases made in 2016 was an 1859 portrait of the Persian syphilitic intellectual prince Jalal al-Din Mirza, dressed in a gold-embroidered suit and posed in front of a European-inspired fringed curtain pulled aside to reveal a distant landscape. In-house and outside scholars continually revise and expand databases about the Asian and Middle Eastern collection’s motifs, makers, materials, authenticity and provenances, partly based on Freer’s own careful recordkeeping of his purchases. ‘The sale catalogues are annotated in his neat tiny writing,’ Farhad says.

The American holdings, although they cannot technically grow, are likewise being expanded with new scholarship. Freer bought more than 50 watercolours by Whistler, the world’s largest collection, which will be the subject of an exhibition in 2019. A team at the Freer has studied the artworks down to the paper’s watermarks and looked for evidence of blotting and scraping. The carefully preserved correspondence shows what Freer was thinking when he made those purchases. ‘America is most fortunate to possess them,’ he told Whistler in 1894, years before he even dreamed about putting up the Washington building that the works would never be allowed to leave.

The Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., reopened on 14 October.

From the October 2017 issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)