From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The era of Charles VII (r. 1422–61) might look to us like an age of faith and chivalry, but for the people who lived through it, the situation did not start out so promising. Charles’s father, sixth of that name, went mad one too-hot day, and drifted in and out of psychosis for much of his life. As the Hundred Years’ War raged on, his reign became a tumble of intermittent battles and epidemics. Bands of under-employed soldiers marauded through the countryside. Then, in 1407, civil war broke out. The dukes of Burgundy aligned themselves with their English in-laws, against their royal French cousins, and the teenaged prince found himself caught up in these family feuds.

The young Charles VII was fumbling and weak-willed. In 1420 he was declared disinherited by the Treaty of Troyes and his exile from Paris continued after his reign officially began in 1422. In 1429, Joan of Arc vowed to do what Charles had not yet been able to, and kick the English out of France. They did not leave, and there was little to suggest that Charles VII would turn out to be a stabilising force in his kingdom. Yet he would eventually preside over a series of durable fiscal and military reforms, and his diplomatic achievements traced the first outlines of France’s modern Hexagon.

The Cluny’s exhibition invites visitors to reconsider a period of challenge and renewal, on the cusp of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Things began to shift in 1435, when Charles VII and Burgundian duke Philip the Good signed the Treaty of Arras; France could not have survived without the truce it brought. It hangs near the exhibition’s entrance, four feet of calligraphied parchment adorned with a dozen solemn red wax seals. Charles VII may have ascended to the throne in chaos, but the kingdom he left behind was at peace.

The Tarascon Pietà (15th century), unknown artist. Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais (musée de Cluny – musée national du Moyen Âge)/Michel Urtado

At the Cluny, the exhibits include diplomatic artefacts, devotional objects, tapestries, stained glass, paintings on wood and canvas, funerary sculptures, military items such as chain mail, and many manuscripts. One notable vitrine displays lead brooches shaped like royal fleurs-de-lis, Saint Andrew (the patron saint of the duke of Burgundy), or scaly dolphins (for the dauphin); these were worn to show political allegiance. Works by the painter Jean Fouquet provide a reference point for the question literally written on the wall: ‘What if the Renaissance dates to Charles VII’s reign?’

Artistic patronage has proven time and again a reliable arm for the aspirations of the newly rich, and Charles’s rule was marked by an important innovation: many of his officers came from bourgeois families rather than the aristocracy. The only book of hours attributed entirely to Fouquet belonged to court officer Étienne Chevalier. (The volume, now scattered, is represented by a single folio from the Bibliothèque nationale de France.) During Charles VII’s reign, France became a crossroads where artists exposed to the technical and stylistic innovations of the Northern and Italian Renaissances laboured within more conservative medieval milieux. Books of hours sit alongside translations of Boccaccio and Cicero, attesting to how changes to class structures create the conditions under which aesthetic avant-gardes emerge – in this case, the stirrings of the French Renaissance.

Book of Tournaments (c. 1462–65), Barthélémy d’Eyck. © Bibliothèque nationale de France

Meanwhile, the court of Charles’s childhood companion René d’Anjou was a second Camelot, dedicated to pageantry and love, yet wonderfully sophisticated in its embrace of Italian habits. The pages of René’s Book of Tournaments, painted by Barthélemy d’Eyck in around 1460, reveal a melee in bright watercolours. The scene spills outwards, overflowing the page’s edge. Only a picket fence protects the viewer from the throng of mounted combatants. A cluster of spectators gathers in the lower right-hand corner, over whose shoulders the viewer looks, as if seated directly behind on a horse of his own. D’Eyck is reworking a medieval trope that casts viewers as pious witnesses.

Many pieces display a dazzling realism. When I leaned over a royal history whose frontispiece depicts the baptism of Clovis, the first Frankish king, I realised the poor man was shivering in his bath (Grandes Chroniques, c. 1429). One pietà made in tempera on wood in Tarascon before 1457 startles, not in its golden haloes or the exorbitantly sculptural lapis folds of the Virgin’s dress, but by Saint John’s expression of concentration as he pinches free the thorns tangled in Christ’s hair.

We return to the exhibition’s first vitrines, and arrive face to face with Joan of Arc, whose relationship with Charles VII remains mysterious and compelling. Legend has it that words Joan spoke to Charles VII restored his confidence during a moment when defeat seemed inevitable (what they were is unknown). He gave her an army, then let her burn at the stake barely two years later. Did Joan herself sign the paper letter on display here from March 1430, promising aid to the people of Reims? Another mystery. The transcript of Joan’s trial lies open to the right. In its margins, a clerk has doodled her likeness, complete with sword and pennant. It is a simple line drawing, but the liveliness of its subject, a teenage girl both seductive and exasperating, comes through in the determined set of her brow.

Charles VII (c. 1450–55), Jean Fouquet. Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Tony Querrec

On the wall adjacent hangs Fouquet’s imposing portrait of the king, the first of its kind, from c. 1450. Charles VII is not a sexy king. He looks beady-eyed in stiff textiles. The contrast between these two renderings, one spontaneous and irreverent, the other severe and scrupulously calibrated, embodies the contradictions of his reign.

Fouquet’s self-portrait – circular, enamelled and only 7cm across – has been placed at the very end of the exhibition. The medallion is displayed in such a way that the visitor can see it only by peering through a roundel cut out of black board. Did Fouquet use a mirror to render this image of himself? His expression is nothing like the averted or distant gazes we have known until now. He stares straight at the viewer. It is like gazing through a porthole and coming face to the face with the future.

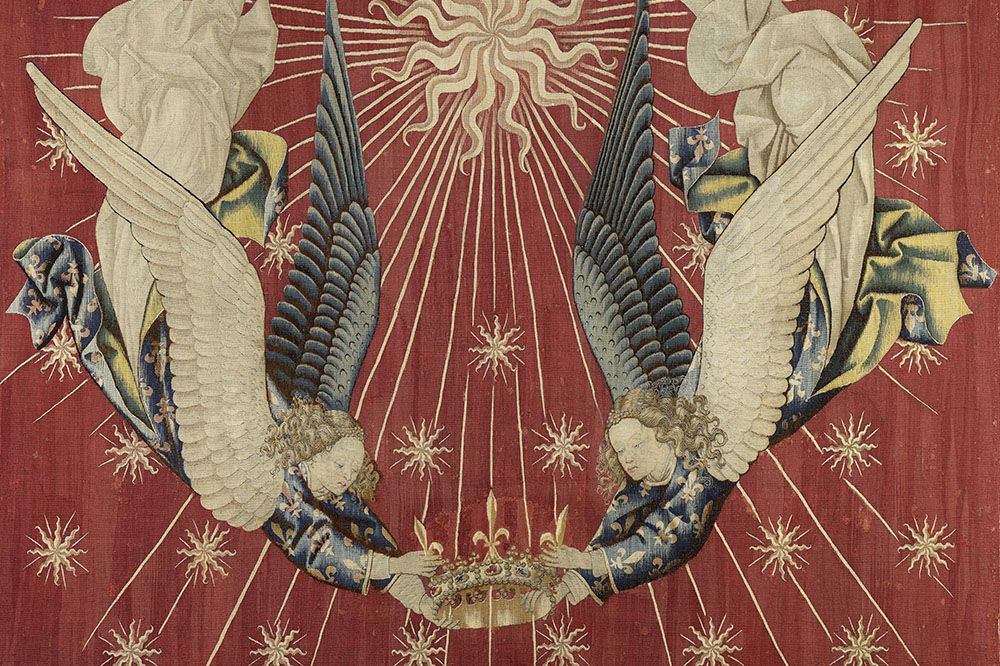

Canopy thought to be for Charles VII’s throne, with two angels holding a crown, (c. 1430–40), after Jacob de Littemont (?). Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Stéphane Maréchalle

‘The Arts in France under Charles VII, 1422–1461’ is at the Musée de Cluny – musée national du Moyen Âge’, Paris, until 16 June.

From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.