It was something of a surprise when Condé Montrose Nast bought Vogue in 1909, as it was when Francois Pinault bought a third of the Condé Nast archive more than a century later. Both purchases turn out to have been judicious, as is made clear by ‘Chronorama: Photographic Treasures of the 20th Century’, on show at the Palazzo Grassi until 1 July.

This exhibition of some early Vogue illustrations and many photographs, not only from Vogue but also other storied titles of the Condé Nast stable such as Vanity Fair, does not show every picture that M. Pinault acquired from the archive. It is a selection organised decade by decade, starting in 1910 and running – perhaps arbitrarily – up to 1970. It is, as such, one story that this portion of an archive can tell. Doubtless, there will be many others.

Actress Anna May Wong (1930), Edward Steichen. Vanity Fair. Photo: © Condé Nast

For now, the curator Matthieu Humery has gone with the big hitters. Works by Andre Kertész, Edward Steichen, Cecil Beaton and George Hoyningen-Huene are scattered about the show. There is no new narrative about the story of fashion photography here. Instead, there is an exquisite affirmation, bold yet polite, of a story many people know: the use of a thoroughly modern medium to replace the older art of illustration. The show speaks of an infatuation with technical ability and composition – one which allows, say, a close-up of woman’s ear and wavy blond hair to be so perfectly shot that it almost becomes illegible. Through this complete freedom with the new medium, fashion photography could become the canvas for broader ideas. Kertész’s photograph of a mannequin wearing a diamond necklace in the shape of a comet and a brooch in the shape of a star is typical in this regard. It is a product shot for a magazine, but it could also be a meditation on the role of models in society in the 1930. It is sly and subtle and also rather witty.

Actress Marlene Dietrich (1932), Cecil Beaton. Vanity Fair. Photo: © Condé Nast

Wit seems to be a characteristic of many of the images that are on display on the first floor of the exhibition, which takes the viewer from 1910 to 1950, yet somehow it recedes as the decades pass. Hoyningen-Huene’s shot of Alexander Calder amid his Circus (1930); Steichen’s self-portrait with a mannequin; Beaton’s portrait of Marlene Dietrich where she exerts all her star-power to outshine a cattleya orchid – each reveals a sensibility that is at once in love with the image and distant from it, leaving space for a joke. Sometimes that space overwhelms the image – as in Cecil Beaton’s shot of debutantes from 1937, in which the shadows behind the debs are not the women in their marvellous frocks but the sinister outlines of men in top hats. Somehow it feels a step too obvious: a rare miscalculation from that master of social appeal.

This selection from the archive hints at one of the baser attractions of this exhibition. It is always a thrill to see famous people in action, whether that is Dietrich, Joan Crawford in Schiaparelli, Katharine Hepburn in a field, Matisse in an aviary, Mia Farrow as Joan of Arc, Duke Ellington in full smiles or Dolly Parton by Irving Penn. If you want a more high-minded flavour of celeb-spotting then how about Aldous Huxley, Susan Sontag or Derry Moore’s portrait of Gilbert and George? Of course, this is exactly why Condé Nast’s stable of magazines was so successful in the mid 20th century. It entranced readers with beautiful pictures of famous people that everyone wanted to get close to. The importance of cinema to this formula is wryly alluded to in another photograph by Steichen of a ‘beach-set’ for a Vogue short film of the 1930s, shot at Fox Studios.

Model in a Balenciaga wedding dress (1967), David Bailey. Vogue. Photo: © Condé Nast

But it wasn’t just the heat of celebrity that was on offer in the pages of Vogue and Vanity Fair. Among the hundreds of portraits and fashion shoots on display, there are a handful of interiors. Perhaps counter-intuitively, these personless pictures reveal much about the attitude of the Condé Nast magazines. Rooms that have been designed by Jean-Michel Frank or Walter Gropius express more crisply than any Balenciaga gown the hard modernism both desired by and promoted in these magazines. African masks that wouldn’t seem out of place in Picasso’s studio; the architects of the United Nations headquarters with trestle-tables for desks; an Isetta bubble car parked by a Moretti apartment – these are images of a trouble-free future, the design lingua franca of a proudly superior elite. As well as a lesson in looks, there is a lesson here in magazine making. Some of the prints are not pristine but wrinkled. A portrait of Jean de Brunhoff bears the thick red strikes of crop marks. These are not the works of photographers alone, but the materials that go to construct the fantasy of editorial.

There is a brief interlude in this painless world which falls, of course, in the 1940s. It might seem mystifying now, but Vogue employed both Cecil Beaton and Lee Miller as war photographers. Lee Miller’s picture of an interrogation of a Frenchwoman whose head has been shaved for consorting with a German in 1944 is shocking. The pictures of a collapsed London by Beaton trip you up with their composed devastation. In an act of curatorial flair, the viewer is moved from a bombed-out Bloomsbury Square to a wrecked Paternoster Row, and then on to a glamorous dinner hosted by Mrs Vanderbilt in a photograph taken by Edward Carswell. The ugliness of the world never held up Vogue.

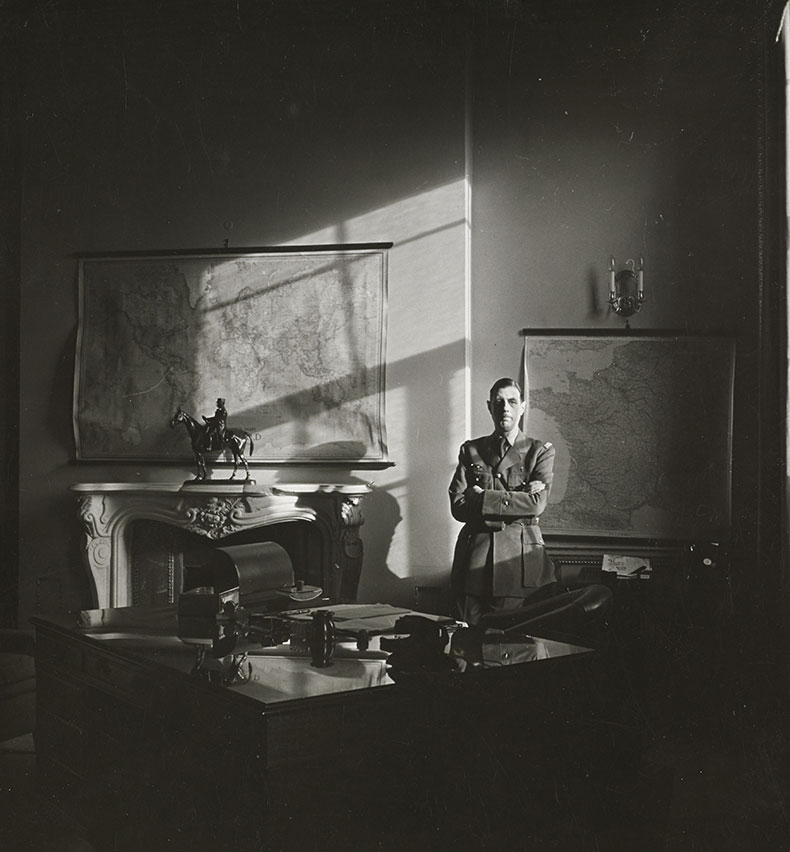

Standing portrait of General Charles de Gaulle (1944), Cecil Beaton. Vogue. Photo: © Condé Nast

Glamour might now seem to be an old-fashioned quality, but the work commissioned by Condé Nast allied it with a very concrete sense of ‘the latest thing’. What ‘Chronorama’ shows is a story old as time: to be truly glamorous, you have to have one foot in the future. For the first half of the 20th century, Condé Nast constructed an image of modernity and disseminated it to Everyman, while the magazines’ proximity to the leading artists of the day secured it the valuable commodity of exclusivity.

As the show continues through the decades, composition gives way to comportment and the shape of the person in the photograph, rather than the form of the picture, becomes the focus of attention. The ‘glamour shot’ takes on another meeting, which possibly reaches its apogee in a work by Helmut Newton, where the form of dress is rendered irrelevant by the hard gaze of the camera feasting on Charlotte Rampling in a swimming pool. The transition to ‘sex sells’ seems to have been mostly accomplished by the 1970s. There’s nothing less adept in the photography, the styling or the production; it’s just that the wit seems to have faded away. But then, thrilling as it is to see from a distance, glamour has always seemed to disappear when you get up close.

Three models, from the series Bathhouse, at the East 23rd Street Swimming Pool, New York (1975), Deborah Turbeville. Vogue. Photo: © Condé Nast

‘Chronorama: Photographic Treasures of the 20th Century’ is at Palazzo Grassi, Venice until 1 July.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)