From the outset of his career until his death this August, Chuck Close played with intimacy. He invited viewers to investigate how close they could come to the surfaces of his paintings and still see the illusion of wondrously realistic portraiture – and then to relish the precise point at which that illusion falls apart, yielding dazzling abstraction. If we’re nose to nose, Close demonstrated, a face is a universe, as full of mystery as the cosmos. The cultural and perceptual registers of scale and proximity have engaged writers from Jonathan Swift to Gaston Bachelard and artists from Van Eyck to Monet to Barnett Newman. Late in his life, it was revealed that Close’s own concerns with social distance didn’t end with painting. Multiple young women reported that after praising their work, he invited them to his studio, where he asked them to strip so he could judge whether they would be suitable subjects for a portrait – accounts that rightfully produced outrage, and a sorry denouement to the career of a larger-than-life artist.

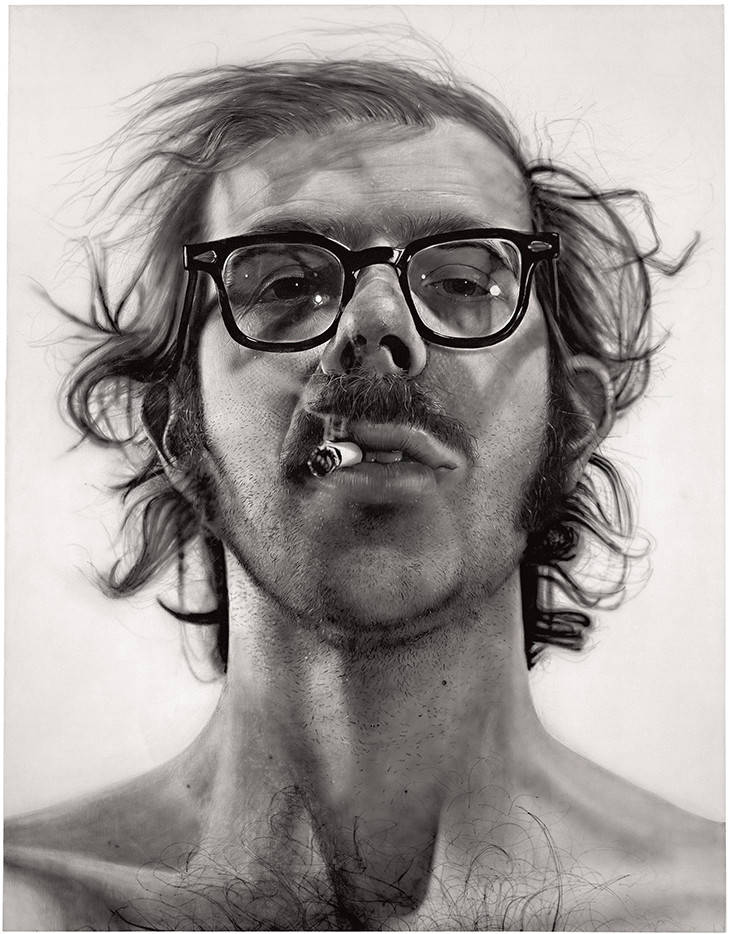

Close’s first self-portrait, of 1967–68, was a stunning achievement of verisimilitude, and also a major, minimalism-be-damned kiss-off. In a black-and-white rendering that makes him seem as big as Mount Rushmore and just as implacable, the artist looks down at us, his chin unshaved and hair dishevelled, a cigarette dangling from his mouth: funny, but sort of chilling. Equally commanding portraits followed, soon in colour, of friends and family. With these aggregated fields of data – that is, photographs replicated with the help of grids, the units first smoothed out with an airbrush, then articulated with swirls of paint – he translated facial features into abstracted information. As early as 1978, the critic Kim Levin likened his paintings to computer screens and called his realism ‘a matter of code’. Though this kind of translation has long since become a digital commonplace, the combination of grandeur and charm in Close’s work remains unique.

Big Self-Portrait (1967–68), Chuck Close. Courtesy Pace Gallery; © Chuck Close

Indeed, critics from Richard Shiff to Robert Storr (the list of his illustrious supporters is long) have praised Close for his deep dive into the relationship between photography and painting – for his successful grafting of the gestural and particular to the impersonal and mirror-hard. A photographer himself, he dabbled in Polaroids and daguerreotypes and explored printmaking and tapestry as well. Along the way, he revealed a considerable amount about the class dynamics of the art world, starting with the down-home familiarisation of his first name (choosing ‘Chuck’ rather than ‘Charles’), and the first-name-only titles of his portraits, mostly of art celebrities, from Phil (Glass) and Roy (Lichtenstein) to Cindy (Sherman) and Kara (Walker). To be a subject was to be anointed. Likewise, to recognise a subject is to be included, an insider. For a long time, Close’s own status was fairly exalted. He was already being called the mayor of SoHo before a medical crisis in 1988 left him paralysed from the neck down; he regained some mobility and the ability to paint, with the help of a brace on his arm, but was thereafter confined to a wheelchair. It became a kind of a throne from which he presided as ambassador-at-large for contemporary art, a position facilitated by the immense popular appeal of his work, and by the good will he generated among colleagues.

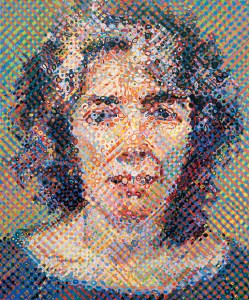

Elizabeth (1989), Chuck Close. Photo: Bill Jacobson/Artifex; © Chuck Close

From the beginning there were social and also physical deficits, most of which Close freely admitted. A raft of medical woes began with childhood neuromuscular problems and included, most tellingly, prosopagnosia, which he said prevented him from recognising faces unless they were reduced to two dimensions. In his mid seventies he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, corrected after a couple of years to frontotemporal dementia, which his neurologist said accounted for his ‘disinhibited’ behaviour – although the sexual harassment evidently predated the dementia. What seems clear is that Close abused both the power and the sympathy he accrued. Deeming rank voyeurism a gift to his victims – they’d been seen! – is a fairly cruel twist, though his conscience doesn’t seem to have bothered him. When I interviewed him in 2015, years after the first alleged harassment occurred but before it was publicly reported, Close judged himself the happiest artist alive. Part of his narrative, it’s worth noting, is that he was a child magician, delighting friends with tricks reliant on distraction and sleights of hand.

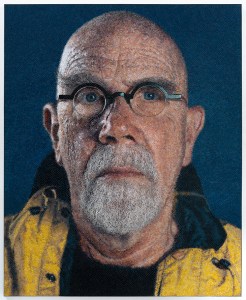

Self-Portrait (Yellow Raincoat)/Micro Mosaic (2019), Chuck Close. Courtesy Pace Gallery; © Chuck Close

Close’s accomplishment is enormous. But I would not argue that it exempts him, or his legacy, from accountability for the damage he caused. As recent recontextualisations of work shadowed by history have shown, we can reckon with serious harm without discarding glorious art. Close has shown us a radiant but treacherously porous world, where what seem reliable boundaries – such as the skin of human faces – prove all too penetrable. It’s a lesson hiding in plain sight.

Boundary issues – the uneasy art of Chuck Close

Big Self-Portrait (1967–68), Chuck Close. Courtesy Pace Gallery; © Chuck Close

Share

From the outset of his career until his death this August, Chuck Close played with intimacy. He invited viewers to investigate how close they could come to the surfaces of his paintings and still see the illusion of wondrously realistic portraiture – and then to relish the precise point at which that illusion falls apart, yielding dazzling abstraction. If we’re nose to nose, Close demonstrated, a face is a universe, as full of mystery as the cosmos. The cultural and perceptual registers of scale and proximity have engaged writers from Jonathan Swift to Gaston Bachelard and artists from Van Eyck to Monet to Barnett Newman. Late in his life, it was revealed that Close’s own concerns with social distance didn’t end with painting. Multiple young women reported that after praising their work, he invited them to his studio, where he asked them to strip so he could judge whether they would be suitable subjects for a portrait – accounts that rightfully produced outrage, and a sorry denouement to the career of a larger-than-life artist.

Close’s first self-portrait, of 1967–68, was a stunning achievement of verisimilitude, and also a major, minimalism-be-damned kiss-off. In a black-and-white rendering that makes him seem as big as Mount Rushmore and just as implacable, the artist looks down at us, his chin unshaved and hair dishevelled, a cigarette dangling from his mouth: funny, but sort of chilling. Equally commanding portraits followed, soon in colour, of friends and family. With these aggregated fields of data – that is, photographs replicated with the help of grids, the units first smoothed out with an airbrush, then articulated with swirls of paint – he translated facial features into abstracted information. As early as 1978, the critic Kim Levin likened his paintings to computer screens and called his realism ‘a matter of code’. Though this kind of translation has long since become a digital commonplace, the combination of grandeur and charm in Close’s work remains unique.

Big Self-Portrait (1967–68), Chuck Close. Courtesy Pace Gallery; © Chuck Close

Indeed, critics from Richard Shiff to Robert Storr (the list of his illustrious supporters is long) have praised Close for his deep dive into the relationship between photography and painting – for his successful grafting of the gestural and particular to the impersonal and mirror-hard. A photographer himself, he dabbled in Polaroids and daguerreotypes and explored printmaking and tapestry as well. Along the way, he revealed a considerable amount about the class dynamics of the art world, starting with the down-home familiarisation of his first name (choosing ‘Chuck’ rather than ‘Charles’), and the first-name-only titles of his portraits, mostly of art celebrities, from Phil (Glass) and Roy (Lichtenstein) to Cindy (Sherman) and Kara (Walker). To be a subject was to be anointed. Likewise, to recognise a subject is to be included, an insider. For a long time, Close’s own status was fairly exalted. He was already being called the mayor of SoHo before a medical crisis in 1988 left him paralysed from the neck down; he regained some mobility and the ability to paint, with the help of a brace on his arm, but was thereafter confined to a wheelchair. It became a kind of a throne from which he presided as ambassador-at-large for contemporary art, a position facilitated by the immense popular appeal of his work, and by the good will he generated among colleagues.

Elizabeth (1989), Chuck Close. Photo: Bill Jacobson/Artifex; © Chuck Close

From the beginning there were social and also physical deficits, most of which Close freely admitted. A raft of medical woes began with childhood neuromuscular problems and included, most tellingly, prosopagnosia, which he said prevented him from recognising faces unless they were reduced to two dimensions. In his mid seventies he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, corrected after a couple of years to frontotemporal dementia, which his neurologist said accounted for his ‘disinhibited’ behaviour – although the sexual harassment evidently predated the dementia. What seems clear is that Close abused both the power and the sympathy he accrued. Deeming rank voyeurism a gift to his victims – they’d been seen! – is a fairly cruel twist, though his conscience doesn’t seem to have bothered him. When I interviewed him in 2015, years after the first alleged harassment occurred but before it was publicly reported, Close judged himself the happiest artist alive. Part of his narrative, it’s worth noting, is that he was a child magician, delighting friends with tricks reliant on distraction and sleights of hand.

Self-Portrait (Yellow Raincoat)/Micro Mosaic (2019), Chuck Close. Courtesy Pace Gallery; © Chuck Close

Close’s accomplishment is enormous. But I would not argue that it exempts him, or his legacy, from accountability for the damage he caused. As recent recontextualisations of work shadowed by history have shown, we can reckon with serious harm without discarding glorious art. Close has shown us a radiant but treacherously porous world, where what seem reliable boundaries – such as the skin of human faces – prove all too penetrable. It’s a lesson hiding in plain sight.

Share

Recommended for you

‘I’m trying to erase myself’ – an interview with Cindy Sherman

The artist has been taking photographs of herself for more than 40 years – but we mustn’t think of the results as self-portraits

Artists’ models are real people – we mustn’t forget this when we look at art

Recent debates over the art of Chuck Close, Balthus, and others remind us of the intertwined nature of ethics and aesthetics

Is the art world too obsessed with celebrity?

Stephen Patience and Kate Bryan wonder if famous faces can make art more accessible – or do they just get in the way?