From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The great chefs learn to cook in Paris. The rest of us, alas, are reduced to Cooking With Paris – a show from Netflix in which that pampered polymath, Paris Hilton, knocks up lasagne and tacos in a well-appointed kitchen somewhere in LA. The show is a learning curve for us all: ‘What do chives look like?’ asks Hilton. ‘I don’t know what “zest of one lemon” means.’

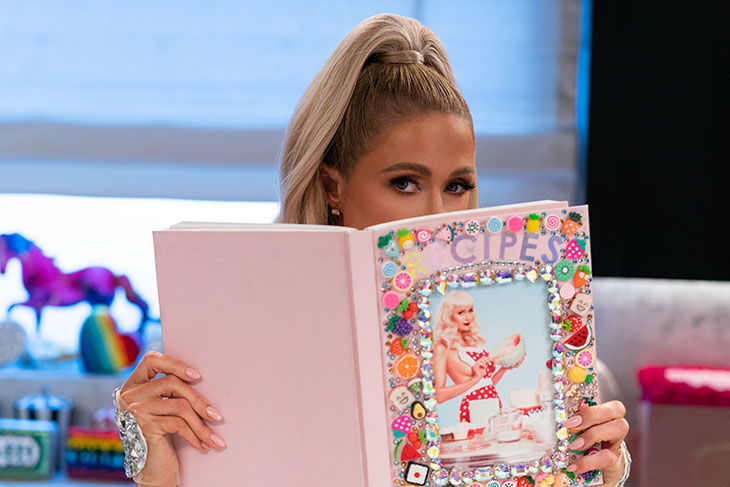

Perhaps surprisingly, given her disregard for their ingredients, Hilton has transcribed all her recipes by hand into a book before embarking on them. She loves writing them out, she says, and has seemingly taken the time to set down, in My Little Pony-coloured felt tips, the successive stages for crafting ‘sliving blue marshmallows’ (don’t ask) and ‘unicorn-oli’ (ditto). The cover of her notebook has been splendidly decorated with various adhesive gems and gewgaws: it looks as though it’s been dipped in Dolly Mixture.

Photo: © Kit Karzen; courtesy Netflix © 2021

The whole show is a knowing joke, of course, a de-luxe lampoon playing up the kitsch in kitchen. But I like the detail of Hilton’s household book, however fantastical or frightening it may be. In its way, if offers a morsel of nostalgic nourishment. Until relatively recently, it was common for cooks to copy out recipes, to collect them in notebooks that were in some sense the paper cousins to the larder. But in 2021, few of us still write out by hand instructions for dishes that we might want to test out or make again. The household book has been superseded by the iPhone note, the BBC Food website and coffee-table cookbooks.

It is fascinating, in this context, to examine household books from Georgian or Victorian kitchens. Although many are lost, plenty survive. Endurance was one of their predilections – hence their many versions of pickling and curing – as well as one of their purposes. These catalogues were not compiled simply to store information, but also to transmit knowledge – whether from household to household, generation to generation, or in the type of kenning that might come from copying a recipe or remedy carefully from a printed source. In some cases, the durability of these books is thanks to their never having suffered the heat of the kitchen; in wealthy households the lady of the house would have copied instructions from her own repository of recipes to hand to the cook. But the manuscript known as Martha Lloyd’s Household Book, which has recently been printed in a colour facsimile with full transcription (Bodleian Library), was kept close to the cooking: the stains on its pages say so.

Lloyd’s recipe collection has a particular historical interest: to Jane Austen, some 10 years her junior, Lloyd (1765–1843) was ‘the friend & Sister under every circumstance’. She lived for many years in the Austen household in Southampton and at Chawton Cottage, Hampshire, now the museum known as Jane Austen’s House and where Lloyd’s household book is part of the collection. Austen would have eaten many of the dishes described here, then, and perhaps referred to the book itself when her sisters and Lloyd were away from home and she took a turn as housekeeper (‘Composition seems to me impossible,’ she wrote on one such occasion in 1816, ‘with a head full of Joints of Mutton & doses of rhubarb.’)

The kitchen at Jane Austen’s House, Hampshire. Photo: Peter Smith

If the Austen connection helps to justify the facsimile volume, it is to the credit of its editor, Julienne Gehrer, that she does not season its prefatory material and annotations too heavily with Janeolatry, focusing instead on Lloyd herself and what the manuscript tells us about food history. All the same, it is interesting to read backwards from these recipes and consider which vegetables and herbs might have grown in the kitchen garden at Chawton, and even to speculate on the relationship between the alimentary and the literary in Austen’s work. (In Austen’s novels, fussing about food is a sign of pretension: in Emma, for example, Mr Woodhouse has too much to say about the best way to cook pork.)

What comes across most vividly from the facsimile, however, is the labour and order that was required in any kitchen of the ‘middling classes’ (as Walter Scott had it) during the Regency period. That orderliness is restated throughout the manuscript in the snugness with which most of Lloyd’s recipes fit to the page (they rarely run over page breaks); the hard work in instructions that never cavil at their own demands (to make a ‘Wallnut Catchup’, ‘[keep] it stirring for eight days’).

With historical recipes, the strangeness of the past is often offset by flashes of familiarity. Here, guidance on how ‘To Hash a Calves Head’ follows fast on that ‘To stew Piggeons brown’ – a dish that, with its anchovy tucked into the gravy, would not look out of place in the latest volume from Nigel Slater. There is a directness, too, in Lloyd’s feeling for making do or improvising (with ‘Snow Cheese’, ‘serve it up with sweetmeats or what you like’) and, conversely, in the exactitude with which she committed recipes to paper (take the correction to the method for ‘Cowslip Wine’: ‘let it stand to be cold a little cool’). Even so, readers who yearn to eat like Jane Austen should be as wary of Martha Lloyd’s household book as they would of one compiled by Paris Hilton: as the editor warns, at least twice, ‘many original recipes […] contain ingredients now known to be toxic’.

Martha Lloyd’s Household Book: The Original Manuscript from Jane Austen’s Kitchen is published by the Bodleian Library.

From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.