In November 1959, two nuns from a Roman Catholic religious order in Los Angeles left for a three-month trip across the world. They started in New York, before crossing the ocean to Paris, Barcelona, Athens, Milan, Cairo and elsewhere. One of the nuns, Sister Mary Corita, took around 8,000 photographs during that trip, a selection of which are projected from slides in the exhibition ‘Corita Kent: La Révolution Joyeuse’ at the Collège des Bernardins in Paris.

These photographs make up half of this compact exhibition and do little to tell us about Kent’s artistic career up to that point, or about how that exposure to so many different cultures in a short space of time influenced her subsequent work. At the time of the trip, she was a member of the Immaculate Heart order; upon leaving and returning to secular life in 1968, she took the name Corita Kent. Many of the photographs she took are religious in nature, such as a detail from a church fresco or the facade of a cathedral. Others are holiday snaps – Kent and her companion Sister Magdalen Mary looking surprisingly relaxed astride camels, Kent taking a selfie in a mirror – but the majority capture seemingly mundane details. Food features a lot, as does her interest in lettering and graphic design: local arts and crafts in a shop in Sicily, traffic signs, cured meats with their prices displayed on sticks in a salumeria, ripped posters fluttering on a wall in a Paris street. But insisting on seeing patterns in that holiday album echoed in her silkscreen prints seems like trying to ascribe meaning where there is none.

The Immaculate Heart College Art Department photographed in c. 1955 by Fred Swartz. Courtesy Corita Art Center, Los Angeles, corita.org

Elsewhere in the show, Kent’s influences are obvious. She may have lived a somewhat segregated life as a nun, but she was alert to the power and mass appeal of popular culture, cloaking her Christianity in the bold colours and flashy advertising style of the time. Her screenprint fish (1964) exemplifies this, juxtaposing the titular word with a scrawled, casual retelling of the biblical story of the miraculous catch of fish: ‘Jesus was knee deep in fish/fish squished against his feet […] but I think jesus was too busy helping pull the nets on board to notice.’ Religion is deformalised, made bright and happy. That’s also why the setting of the exhibition, a former Cistercian college, works so well. The prints are a dense burst of neon and colour against the beige stone of the college’s former sacristy – as incongruous as a nun making Pop art.

passion for the possible (1969), Corita Kent. © 2024, Corita Art Center, corita.org

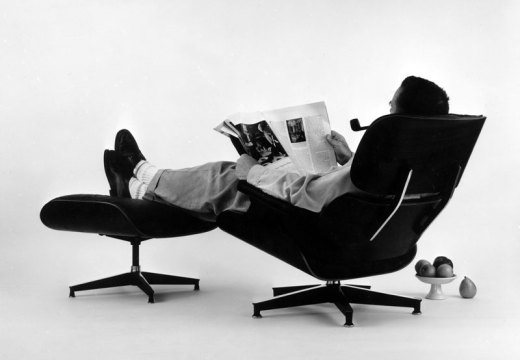

Kent had a voracious cultural appetite and was keenly aware of what her contemporaries were doing. She was friends with Ray and Charles Eames, John Cage, Alfred Hitchcock and Saul Bass. It was after seeing Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans when they were shown for the first time in Los Angeles in 1962 that she created her series inspired by Wonder Bread, riffing off the cheerful primary palette of the American brand. Her print wonderbread (1962) takes the dots from the brand’s packaging and recasts them as Communion wafers, and she scandalously brought together the Virgin Mary and the tinned vegetables brand Del Monte by declaring that ‘Mary Mother is the juiciest tomato of them all’ in a print of 1964, an echo of which is found here in the later piece tomato (1967). Her playful attitude towards Scripture drew the ire of the Archbishop of Los Angeles James McIntyre, and this conflict between the state’s diocese and the progressive attitude of the Immaculate Heart order eventually led Kent to renounce her vows in 1968. However, we see nothing of this row in the body of the exhibition itself, and the show’s lack of chronology masks the evolution of her artistic concerns, which became more political as time went on.

Her social activism is muted in the chosen pieces, which seems a misstep, especially for a show in a country with a strong tradition of revolutionary slogans and street protests filled with the posters and banners that find their echo in Kent’s work. We see a few pieces from her Heroes & Sheroes series (1968–69), including the cry that will be heard, a collage of a Life magazine cover from 1968 alongside song lyrics that exhort the listener to ‘give a damn about your fellow man’. To make her print stop the bombing (1967), Kent used a photograph of a crinkled newspaper headline to recreate the visual effect of the distorted letters, but exhibited here on its own, it is made to seem like an outlier in a body of work that increasingly leaned towards activism from the late 1960s onwards. ‘La Révolution Joyeuse’ is the first exhibition dedicated solely to Kent’s work in France but, disappointingly, it’s all joy and little revolution.

stop the bombing (1967), Corita Kent. © 2024, Corita Art Center, Los Angeles, corita.org

‘Corita Kent: La Révolution Joyeuse’ is at the Collège des Bernardins, Paris, until 21 December.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)