Francis Bacon perches uncomfortably on the edge of the bed: eyebrows furrowed, sleeves of his pullover rolled up, and staring through cigarette smoke at the great bear of a man beside him who looks considerably more at home in Bacon’s bedroom. This interlocutor has the styled ease, the bulk, the bald patch and the dark suit of Ambroise Vollard in Renoir’s famous portrait – the resemblance, in fact, is uncanny – and he scrutinises his subject with the same intensity as Vollard does the classical statue in his hands.

‘Do you not think,’ he posits, ‘that the marks you are making are both a caress and a blow? An assault?’

‘I think this thing is’ – Bacon stutters, slurring his words – ‘I think it goes to a deeper thing than this. I think it’s how do I feel – and this can only be feeling – how can I make this image more immediately real to myself. That’s all.’

Three times Bacon tries to bat away this line of questioning, claiming that all he’s interested in is ‘immediacy’ in his portraits, and certainly nothing like ‘cruelty’. But sensing that Bacon is rattled, the interviewer presses home the advantage. ‘What you’re saying,’ Bacon is eventually goaded into saying, ‘is what Wilde said. You kill the thing you love.’

Perhaps the single defining feature of the life and thought of David Sylvester, who was born 100 years ago this week, is that for him the stakes of art criticism were raised to a level scarcely imaginable today. His interview with Bacon, broadcast on the BBC in 1966, is one between friends who had become close over the previous 15 years – but it is nothing short of gladiatorial. John Berger is often described as Sylvester’s great rival of the 1950s, but the word is too polite – for Sylvester, he was an enemy. Aghast at Berger’s failure to grasp the significance of Bacon and Giacometti, Sylvester chastised him with the words: ‘Someone with the stance of a prophet has to be on the right side when the battle is at its height.’

Up for grabs were both the future of modern art in post-war Britain, and the shape and function of criticism itself. It does not seem too great an oversimplification to suggest that these spoils were cleanly divided. Berger is far more influential today as a writer. By 1951 he had begun smuggling terms and concepts from Marxist cultural theorists such as Walter Benjamin into the pages of the New Statesman (then the New Statesman and Nation). ‘Because he employs words like “formalist” and “content”,’ recounted his friend, the painter Peter de Francia, in 1957, ‘he quickly came to be regarded as a kind of homicidal iconoclast’. But by the time he came to write Ways of Seeing (1972), and to film the four-part TV adaptation of this book for the BBC with Mike Dibb, Berger had managed not only to achieve a fusion of social theory with art criticism that would prove highly influential in academic spheres, but somehow also to make his approach popular.

And yet, as de Francia also observed, ‘the campaign he waged produced practically nothing in terms of painting or sculpture’. The social realist painters on whom Berger hung his theories in the ’50s – John Bratby, Derrick Greaves – are today known principally by the derisive epithet of ‘Kitchen Sink’ painters, coined by Sylvester in a broadside of 1954. (‘Everything but the kitchen sink? No, that too,’ as he dismissed their focus on the humdrum trappings of everyday life.) They reclaimed the term as a badge of honour, and their critical reputation as precursors to Pop has recovered somewhat in recent years, but they remain very far from being household names.

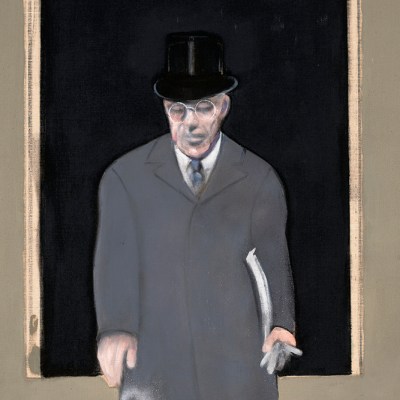

For Sylvester, the point of criticism was so simple that you had to be stupid not to get it: ‘to defend one’s position and the artists one admires, and to have a go at what one sees as corrupting forces.’ There is much in Sylvester’s thought that smacks, like this, of so much ‘good old British common sense’ – but there is also the inescapable fact that the artists he admired have with few exceptions won starring roles in the story of 20th-century art. He championed Bacon, Lucian Freud, Henry Moore and Richard Hamilton in the 1950s, while also opening British eyes to Miró, Giacometti and Dubuffet. He went out to bat for Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg and Robert Morris in the 1960s and ’70s, and by the 1980s was praising Richard Long’s walks and teasing out the debt of Gilbert & George to Magritte.

Sylvester’s father was a Russian-Jewish antiques dealer in London. He was thrown out of the family home at 16 (like Bacon) for causing trouble at school, trying his hand unsuccessfully as a dealer and then a painter. An encounter with the ‘sustained tension’ of Matisse’s La Danse encouraged him to submit an article on drawing to Tribune in 1942, thereafter writing book reviews for George Orwell (Tribune’s literary editor from 1943) until the end of the Second World War. His barbs at Berger in the early 1950s were largely aimed via the pages of Encounter; Sylvester also wrote for The Listener, The Times and others until, in 1960, he took over Berger’s role of art critic for the New Statesman.

His tools were few, but they were sharpened with practice and, wielded in combination, could be punishing. Like Clement Greenberg’s at its best, his prose does not transport us into his mind but rather out of his eyes, concentrating intently on the work in front of him, of us. ‘The eye must not rest, it must allow itself to be forced away from the centre to find a point at which it can enter the composition […] and so journey through the picture, “taking a walk with a line”,’ he tells us in an early piece from 1948 on late Paul Klee. Or here, on Bridget Riley in 1963: ‘The forms are more compact, more centripetal, and also appear to be within reach – claustrophobically so; it would often be more apt to say we were in reach of them.’ Or this, from 1961: ‘Faced with Rothko’s later paintings in the exhibition at Whitechapel one feels oneself unbearably hemmed in by forces buffeting one’s every nerve, imagines the gravity of one’s body to be multiplied as if some weight borne on one’s shoulders were grinding one into the ground.’ No archival reconstruction, no catalogue, no film can so immediately or intensely reconstruct the feeling of actually being in these galleries, seeing these exhibitions. Sylvester’s writing is an education in looking, but Sylvester is not the teacher. The artwork is. He is sitting at the desk beside us, taking notes.

This is not to say Sylvester was shy about asserting his authority, far from it. He was fond of the word ‘finest’ – Riley’s work is ‘among the finest of its kind being done anywhere’, Dubuffet is ‘the finest European painter of his generation’. These conferrals of value were always to individuals – Sylvester was wary of ‘schools’, and disdainful of debates over, say, the validity of figuration versus abstraction. All that mattered was the intensity of the encounter – the ability of the work, as he wrote of Kossoff’s in 1995, to succeed ‘in trapping appearance in a way that is convincing and moving and new’. When he found work that did this, he often set out to befriend the artist – a further effort to get under the skin of the work, but surely also harbouring the expectation that, through a carefully placed bon mot or two, he could have a vicarious influence on its direction.

From the 1960s, Sylvester increasingly sought means other than writing to leave his stamp on modern art. He had a seat on the Arts Council, was a trustee at the Tate, curated a Renoir show at the Hayward with a young Nicholas Serota in 1969, and in 1967 accepted a commission from Jean and Dominique de Menil to write a catalogue raisonné of Magritte, which took him 25 years. (‘I still love the work,’ he wrote after finally finishing it, ‘but the fact remains that I spent years of my life, like Swann, on someone who was not my type.’) In 1993, he became the first critic (rather than artist) to be awarded the Golden Lion at Venice, for the survey he curated of Francis Bacon, who had died the previous year.

Sylvester attributed his adulation by the establishment to being an outsider – and yet, for much of his life, there was really nobody else so comprehensively inside modern art in Britain. Taken as a whole, his collected efforts can look today like a career-long exercise in canon-building. It is a canon overwhelmingly white and male, and one that maps uncannily on to the league table of record-breakers at auction. But then, what Sylvester’s writing alerts us to above all is the danger of being too broad brush.