It’s easy to imagine a world in which the launch of Digital Benin – the first comprehensive catalogue of more than 5,240 known Benin Bronzes across the world, which launched online this week – might have been taken by certain commentators as evidence that restitution was unnecessary. When it was first envisioned around five years ago by Barbara Plankensteiner at the MARKK museum in Hamburg, responding to requests from Nigerian scholars – and even when, with funding to the almost unprecedented tune of €1.2m from the Ernst von Siemens Foundation, the project got underway in 2020 – it would have seemed fanciful that the German government would soon commit to returning all of the Benin Bronzes in its museums to Nigeria. It did so in April 2021, and an agreement with Nigeria for the legal transfer of ownership was signed in July this year. Digital Benin might well have ended up by far the most ambitious, but nonetheless the latest in a long line of projects that have sought, with the prospect of physical returns apparently politically impossible, the compromise of making online resources more readily available to those lamenting lost treasures. Now, with the restitution landscape irrevocably changed, the project feels like nothing so much as a loving farewell.

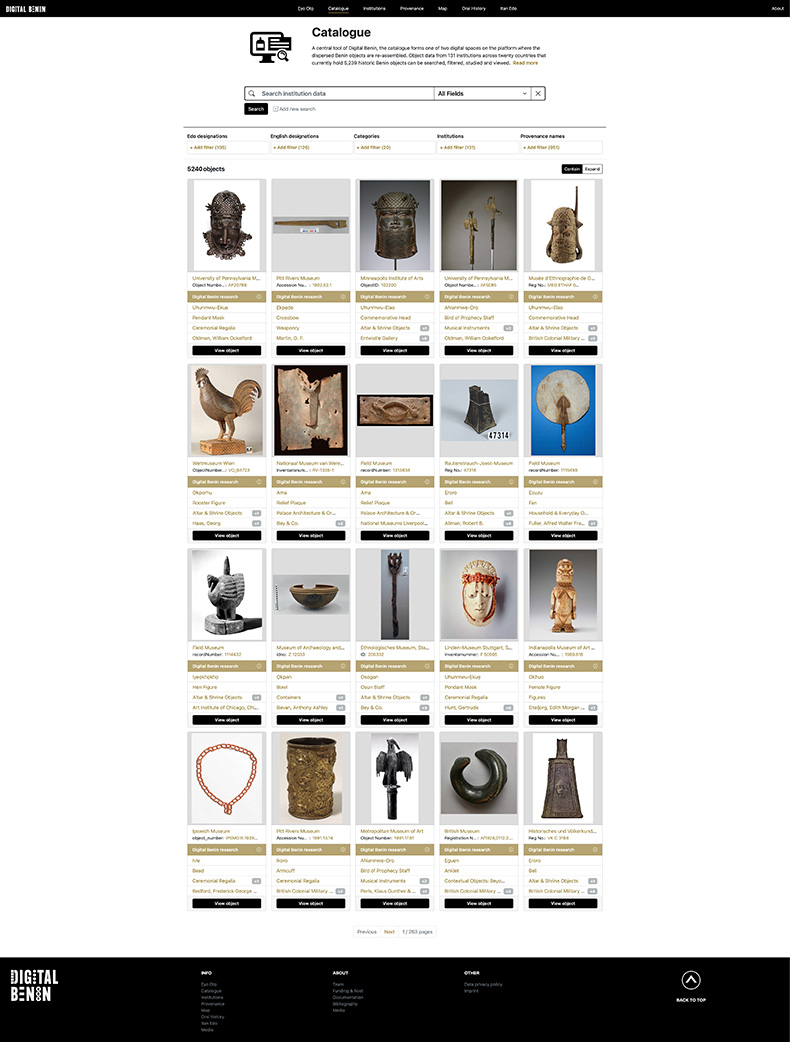

A screenshot from the Digital Benin online catalogue

In a funny twist of fate, Digital Benin should come as no small consolation to those in the West who still decry the prospect of ceding ownership of the Bronzes. It is a remarkable achievement; the resources here offer deeper, richer and more rewarding engagement with the history and meaning of these artefacts than anything yet provided by any Western museum. The catalogue can be filtered by category in both English and Edo (the kingdom of Benin lies within what is now Edo State in Nigeria), as well as by provenance and by institution. There is a separate section dedicated to provenance – where the fact most immediately apparent is that far and away the most common mode of acquisition is the British punitive expedition of 1897, when Benin City was sacked and the Oba (king) deposed. This provenance is shared by 1,427, about a third, of all Benin objects compiled here. Among the other the names on this list are dealers, diplomats, colonial officers, ethnographers and dignitaries of the Benin court, each with biographical information that enables users of the site to trace the complex routes by which objects ended up scattered across the Global North. There are two interactive maps – one giving an insight into important sites within the former kingdom of Benin, and the other showing the location of all known Benin Bronzes in museums worldwide. (Five institutions holding Benin works are in the southern hemisphere – three in Australia, and two in Nigeria. The other 126 are in the north.)

Previous efforts, notably by Kathryn Wysocki Gunsch in The Benin Plaques: A 16th Century Imperial Monument (2017) and Dan Hicks in The Brutish Museums (2020), have been made to reconstruct a catalogue of the Bronzes. Neither is as comprehensive, nor boasts such a wealth of supplementary materials as this one. But what really sets Digital Benin apart is the balance it has managed to strike between English and Edo materials. There is a page dedicated to oral testimonies from Edo sources, and another titled ‘Eyo Oto’ – a phrase used by the Edo when the foundations of a new building are laid. As such, the researchers are expressing a certain degree of modesty, calling this ‘foundational research into the naming of historical objects in their Edo context’.

Oral history interview with Roseline Ogbodu in Benin City, 2022. Photo: © Osaisonor Godfrey Ekhator-Obogie

One of the most often-cited causes for regret among Edo historians is that, with the sacking of Benin, so much of the kingdom’s cultural memory, which inhered in the relative position of plaques and other sculptures within the Oba’s palace dating back to the 15th century, had been lost – volumes of a previously coherent history scattered as though through Jorge Luis Borges’ Library of Babel. At a launch event on Wednesday evening, project research lead Osaisonor Godfrey Ekhator-Obogie said: ‘Every bronze plaque that you see here was a page in the history of Benin.’ Digital Benin’s greatest legacy will rest on whether it can help the Edo to begin in earnest the painstaking process of piecing them back together, in preparation for the long-awaited arrival of the physical objects themselves. The further these efforts advance – the nearer the prospect of a museum in Benin City that can restore the cohesion of one of the world’s great artistic ensembles – the more the stance of British Museum chair George Osborne, who doubled down this week in saying that the museum will refuse to be caught ‘in the maelstrom of the [restitution] moment’, will come to seem like petulance in the face of progress.

There have been suggestions that the project might provide a model for negotiating the fate of other contested objects – for instance, the Parthenon marbles. With €5m, five years and the right personnel, Anne Luther, the digital humanities expert at the helm of Digital Benin, told the Financial Times that she could track ‘all objects in all institutions’. One can see how this kind of project might pour fuel on the fire of the argument for the return of certain objects, such as the Maqdala treasures of Ethiopia, or the gold looted by the British from the Asante of modern-day Ghana – but context is key, especially in an environment where refusing the return of the Benin Bronzes is often justified by the ‘slippery slope’ fallacy. The case of the Parthenon is far more likely to be settled by the advent of 3D replicas than by this kind of knowledge-sharing platform.

Relief plaque depicting a king with two dignitaries (16th/17th century), Kingdom of Benin. Photo: Paul Schimweg/Museum am Rothenbaum MARKK

For her part, Barbara Plankensteiner has pointed out that Digital Benin is a ‘parallel process’ to restitution. ‘We call it a knowledge platform because it will create new knowledge,’ she has stated. Above all, the platform is a triumph for collaboration over confrontation – and as such, it points to a paradigm shift. Where the ‘universal museum’ of the 20th century attempted to house world history in a single building, perhaps Digital Benin lays the foundations for a new kind of universal museum – one which brings perspectives and expertise from across the globe to bear in elucidating the world’s heritage as never before.

View the catalogue: digitalbenin.org

Digital Benin opens a new chapter in the restitution saga

Armcuff Digital Benin

Share

It’s easy to imagine a world in which the launch of Digital Benin – the first comprehensive catalogue of more than 5,240 known Benin Bronzes across the world, which launched online this week – might have been taken by certain commentators as evidence that restitution was unnecessary. When it was first envisioned around five years ago by Barbara Plankensteiner at the MARKK museum in Hamburg, responding to requests from Nigerian scholars – and even when, with funding to the almost unprecedented tune of €1.2m from the Ernst von Siemens Foundation, the project got underway in 2020 – it would have seemed fanciful that the German government would soon commit to returning all of the Benin Bronzes in its museums to Nigeria. It did so in April 2021, and an agreement with Nigeria for the legal transfer of ownership was signed in July this year. Digital Benin might well have ended up by far the most ambitious, but nonetheless the latest in a long line of projects that have sought, with the prospect of physical returns apparently politically impossible, the compromise of making online resources more readily available to those lamenting lost treasures. Now, with the restitution landscape irrevocably changed, the project feels like nothing so much as a loving farewell.

A screenshot from the Digital Benin online catalogue

In a funny twist of fate, Digital Benin should come as no small consolation to those in the West who still decry the prospect of ceding ownership of the Bronzes. It is a remarkable achievement; the resources here offer deeper, richer and more rewarding engagement with the history and meaning of these artefacts than anything yet provided by any Western museum. The catalogue can be filtered by category in both English and Edo (the kingdom of Benin lies within what is now Edo State in Nigeria), as well as by provenance and by institution. There is a separate section dedicated to provenance – where the fact most immediately apparent is that far and away the most common mode of acquisition is the British punitive expedition of 1897, when Benin City was sacked and the Oba (king) deposed. This provenance is shared by 1,427, about a third, of all Benin objects compiled here. Among the other the names on this list are dealers, diplomats, colonial officers, ethnographers and dignitaries of the Benin court, each with biographical information that enables users of the site to trace the complex routes by which objects ended up scattered across the Global North. There are two interactive maps – one giving an insight into important sites within the former kingdom of Benin, and the other showing the location of all known Benin Bronzes in museums worldwide. (Five institutions holding Benin works are in the southern hemisphere – three in Australia, and two in Nigeria. The other 126 are in the north.)

Previous efforts, notably by Kathryn Wysocki Gunsch in The Benin Plaques: A 16th Century Imperial Monument (2017) and Dan Hicks in The Brutish Museums (2020), have been made to reconstruct a catalogue of the Bronzes. Neither is as comprehensive, nor boasts such a wealth of supplementary materials as this one. But what really sets Digital Benin apart is the balance it has managed to strike between English and Edo materials. There is a page dedicated to oral testimonies from Edo sources, and another titled ‘Eyo Oto’ – a phrase used by the Edo when the foundations of a new building are laid. As such, the researchers are expressing a certain degree of modesty, calling this ‘foundational research into the naming of historical objects in their Edo context’.

Oral history interview with Roseline Ogbodu in Benin City, 2022. Photo: © Osaisonor Godfrey Ekhator-Obogie

One of the most often-cited causes for regret among Edo historians is that, with the sacking of Benin, so much of the kingdom’s cultural memory, which inhered in the relative position of plaques and other sculptures within the Oba’s palace dating back to the 15th century, had been lost – volumes of a previously coherent history scattered as though through Jorge Luis Borges’ Library of Babel. At a launch event on Wednesday evening, project research lead Osaisonor Godfrey Ekhator-Obogie said: ‘Every bronze plaque that you see here was a page in the history of Benin.’ Digital Benin’s greatest legacy will rest on whether it can help the Edo to begin in earnest the painstaking process of piecing them back together, in preparation for the long-awaited arrival of the physical objects themselves. The further these efforts advance – the nearer the prospect of a museum in Benin City that can restore the cohesion of one of the world’s great artistic ensembles – the more the stance of British Museum chair George Osborne, who doubled down this week in saying that the museum will refuse to be caught ‘in the maelstrom of the [restitution] moment’, will come to seem like petulance in the face of progress.

There have been suggestions that the project might provide a model for negotiating the fate of other contested objects – for instance, the Parthenon marbles. With €5m, five years and the right personnel, Anne Luther, the digital humanities expert at the helm of Digital Benin, told the Financial Times that she could track ‘all objects in all institutions’. One can see how this kind of project might pour fuel on the fire of the argument for the return of certain objects, such as the Maqdala treasures of Ethiopia, or the gold looted by the British from the Asante of modern-day Ghana – but context is key, especially in an environment where refusing the return of the Benin Bronzes is often justified by the ‘slippery slope’ fallacy. The case of the Parthenon is far more likely to be settled by the advent of 3D replicas than by this kind of knowledge-sharing platform.

Relief plaque depicting a king with two dignitaries (16th/17th century), Kingdom of Benin. Photo: Paul Schimweg/Museum am Rothenbaum MARKK

For her part, Barbara Plankensteiner has pointed out that Digital Benin is a ‘parallel process’ to restitution. ‘We call it a knowledge platform because it will create new knowledge,’ she has stated. Above all, the platform is a triumph for collaboration over confrontation – and as such, it points to a paradigm shift. Where the ‘universal museum’ of the 20th century attempted to house world history in a single building, perhaps Digital Benin lays the foundations for a new kind of universal museum – one which brings perspectives and expertise from across the globe to bear in elucidating the world’s heritage as never before.

View the catalogue: digitalbenin.org

Share

Recommended for you

Are frictions in Nigeria jeopardising the return of the Benin Bronzes?

With cracks appearing in the relationships of institutions in Nigeria, Barnaby Phillips wonders where the returned Benin Bronzes are going to end up

Private enterprise – the individuals who are taking restitution into their own hands

While museums deliberate about returning objects that were taken from their places of origin without consent, it is easier for individuals to act

The Benin Bronzes are not just virtuoso works of art – they record the kingdom’s history

Benin City will soon have a permanent display of its court bronzes for the first time in over a century. What makes these artworks so extraordinary?