Like jazz and rock before it, electronic music has reached the point of accumulating enough history to start looking back and thinking about its heritage. This is an especially ironic moment for a medium that has been so consistently associated with the future, not just in its sounds but in the visual language that surrounds it, the lifestyles it promotes, and the stories it seeks to tell. With electronic music now providing a pretext for retrospectives, reissues and museumification, there is a risk that its tomorrows could be turned into yesterdays, that its surprises and possibilities congeal into reference points and hagiographies.

Unlike jazz and rock, electronic music as a medium is, strictly speaking, defined by technologies rather than groups of people at particular times and places. Thus, to speak of ‘electronic music’ as a category is to unite groups and contexts as disparate as the state-funded studio avant-gardism of Europe in the 1950s and the predominantly black and Latinx gay clubs of Chicago and New York. Over time, the term has shifted to include the latter, though it has taken longer than it should have done. Thirty years ago, a book on ‘electronic music’ would have principally covered composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Schaeffer, and the appeal of an exhibition in a design museum on the topic wouldn’t have been obvious. But today, the term has been adopted and championed in areas of popular music where guitar music is now less fashionable than cyborg poetics, or where factions within what used to be called ‘dance music’ have coalesced around the history and prestige of house, techno and all things analogue.

Untitled (The Endless Summer) (2007), Bruno Peinado. Installation view of ‘Electronic: From Kraftwerk to The Chemical Brothers’ at the Design Museum, London. Photo: Felix Speller

At the Design Museum, techno can be heard over speakers right from the start, and the space’s black walls, blue spotlights, mesh panels and bare scaffolding are clearly intended to evoke the club. Nevertheless, the space remains recognisably that of a museum, inviting anthropological reflection, and with the notable exception of some fashion and photography and installations, much of its contents are objects that supported the club but circulated outside it: records, instruments, magazines, advertisements. The result is a somewhat inevitable indirectness, with exhibits offering historical associations more often than an aesthetic experience of the club itself, despite appearances. One of the clearest examples of this is the metal flight case that carried techno pioneer Jeff Mills’s records around the world in the 1990s, an otherwise unassuming object with an almost purely historical aura.

Even with dance music at its centre, the exhibition faces the same conundrums of inclusion and veneration that any attempt to define electronic music would. The subtitle, ‘from Kraftwerk to the Chemical Brothers’, implies both popular music and big-name acts – and both groups contribute video installations to the exhibition. Yet the span of time between Kraftwerk (formed in 1970) and the Chemical Brothers (formed in 1989), even if it does encompass the birth of both house and techno, is much shorter than the period covered by both the medium of electronic music and the exhibition itself, which begins with a nod to the earliest electronic instruments in 1901 and extends to newer acts such as FKA Twigs. The pre-club history of electronic music is covered hurriedly in a single room featuring album sleeves on the wall, early synthesisers, and a timeline that segments the history of electronic music rather too readily into specific periods. In one place it makes the loaded claim that ‘it was not until the 1960s that real electronic music appeared’. ‘Electronic Music’ is precisely what Stockhausen and other composers in Germany had been calling their work since the early 1950s. On the other hand, the exhibition as a whole extends ‘electronic music’ rarely, if at all, to hip hop (even those forms of it that have used drum machines, vocoders, and synthesisers), grime, or scenes in the Caribbean, Latin America, Asia, or Africa.

Union Rave (1995), Andreas Gursky. Installation view of ‘Electronic: From Kraftwerk to The Chemical Brothers’ at the Design Museum, London. Photo: Felix Speller

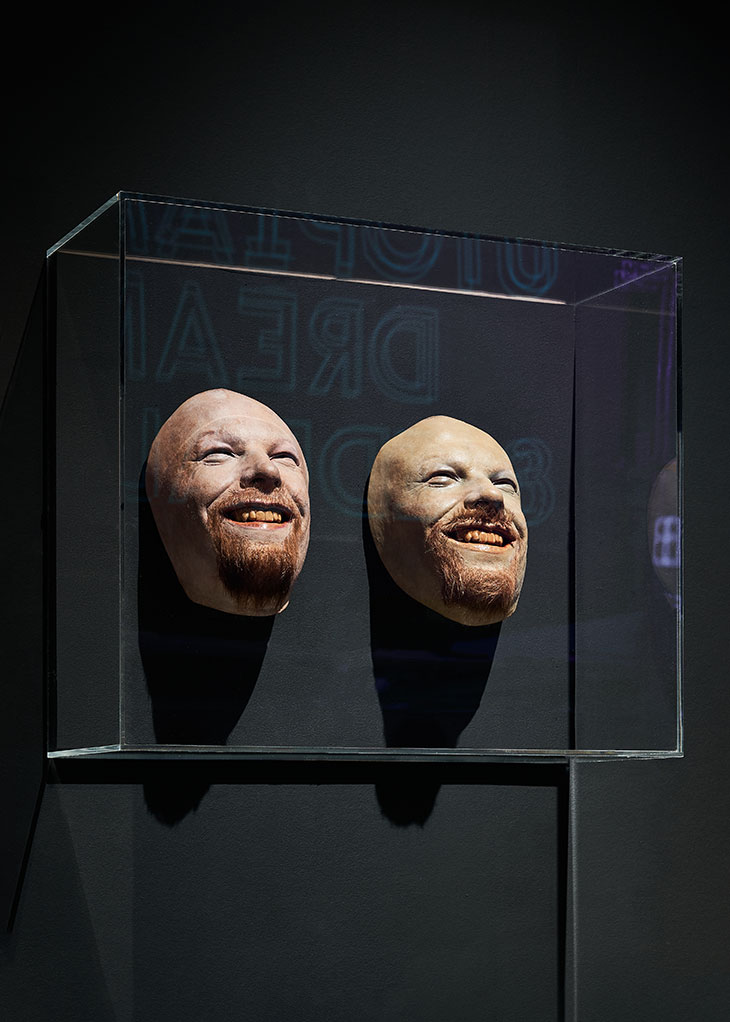

Whatever its claims to present ‘electronic music’ in the round, the exhibition’s strengths – as one might expect – lie in its attention to the vivid and variegated imagery surrounding club culture and the artefacts that have emerged from it. Most engrossing are the cases full of flyers and walls of posters dedicated to legendary parties and venues, and photographs of nightlife: Tina Paul’s vivacious yet tender portraits of queer clubbing, or Andreas Gursky’s panoramas of hundreds of ravers, which now seem both obscene and elegiac in a time of social distancing (the museum has reduced capacity and lets in visitors – all of whom are required to wear a mask – at pre-arranged intervals). Much of the exhibition is arranged according to scenes – Detroit, Chicago, New York, British rave – but its most interesting curatorial gestures are made according to theme, such as the section devoted to the medium’s predilection for masks, including those notoriously worn in Aphex Twin’s videos.

Installation view of masks from the Aphex Twin video Windowlicker (1999), in ‘Electronic: From Kraftwerk to The Chemical Brothers’ at the Design Museum, London. Photo: Felix Speller

Less convincing are the exhibition’s ambitions beyond design, and the forays of its wall texts into history and sociology are sometimes given to generalisation or the odd inaccuracy: Chicago duo Phuture, who famously made the epochal ‘Acid Trax’ in 1987, complicate the show’s claim that Manchester club The Haçienda was ‘where house became acid house’. Coverage of the past and present political struggles of dance culture and its communities is timely and commendable – Afrofuturism is explained and explored, and feminist groups such as female:pressure and Discwoman appear – though more explicit inclusion of cis and trans women elsewhere in the exhibition would have gone further in embodying this politics and doing the ongoing work of realigning the way electronic music’s story has been told.

The Design Museum’s exhibition does not fail to show electronic music (or dance culture) as a lively and heterogeneous system of interlinked worlds that have forged the future, but it may leave those who are already immersed in it ambivalent about its choices of focus, or the way in which so much of it venerates established icons of the past. To whatever extent ‘electronic music’ is indeed a coherent historical and cultural field, this exhibition offers another iteration of an ongoing process in which its past, present and future are always in flux, always appearing anew.

‘Electronic: From Kraftwerk to The Chemical Brothers’ is at the Design Museum, London, until 14 February 2021.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)