From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Elisabeth Frink said that her sculptures are ‘about what a human being or animal feels like, not what they necessarily look like’. This quotation appears on the wall of a new exhibition of her work in the Weston Gallery of Yorkshire Sculpture Park. In the centre of the room are four monumental heads that dominate the space, but when I visited my eye was drawn to a small cluster of her earlier works from the 1950s and ’60s. These are tortured, desiccated forms, seemingly in a state of decay. They have an anthropomorphic quality – Vulture (c. 1952), for instance, is hunched and human-like, while Cat (1953) is an unsettling work; the body of the cat is contorted as if in pain, its face is arrestingly half-human, with enlarged, open eyes and an unfeline mouth like a letterbox. If Frink’s work is about what it feels like to be one of these creatures, we can only wonder what torment they have suffered.

It’s tempting to think that these sculptures, created in the decade after the end of the Second World War, are the work of an artist for whom the collective trauma of conflict was still fresh. This was, of course, the period in which a group of young British sculptors, including Lynn Chadwick and Eduardo Paolozzi, came to be labelled the ‘Geometry of Fear’ school. Frink was younger than these artists, but there is a noticeable difference between the work she made in the years after the war and the gentler, more pedestrian forms of the middle part of her career, such as Dog II (1980), a life-like, somewhat anodyne sculpture of a Vizsla.

Cat (1953), Elisabeth Frink. Photo: Jonty Wilde; courtesy Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Frink made her pieces by building up plaster on a wire armature and then working it with a chisel – or in some cases an axe – once it was dry. The finished piece was then cast in bronze. In the earlier forms, the bronze holds the shapes of sticky clumps of plaster and in places is hacked and scored. Later on, the work is often smoother, with a softer silhouette. As a way of working, this practice is both constructive and destructive – about the drama of presence and absence; layering material, but also hewing away at it, risking the loss of previously worked shapes and forms.

Frink is perhaps most famous as a sculptor interested in raw masculine strength, in brutality and in power, but a less well-known aspect of her oeuvre is the narrative work, much of it on paper. In etchings and screenprints, Frink took on the tangled webs of mythology, folklore and English literature, as in The Canterbury Tales (1972) – her first etchings – and the Children of the Gods series (1988). The female body is rare in her work (I’ve yet to see a three-dimensional female form in her corpus), but when pushed by the demands of a narrative, Frink did occasionally depict women. It’s wonderful, then, to see her etching and aquatint of Hades and Persephone (1988) in the exhibition. The image is dominated by the horse drawing Hades’ chariot. In the upper part of the composition is Hades, his eyes blacked out, recalling Frink’s famous series of sculptures of men with goggles. He holds the naked, fragile form of Persephone like a rag doll. Frink is at her most unsettling when depicting the power imbalances between men and women. Persephone is helpless, as the god of the underworld thunders back to his realm holding her in his clutches.

Ganymede (1988), Elisabeth Frink. Photo: © Frink Estate; courtesy Yorkshire Sculpture Park

One of the joys of this exhibition is the way it presents work from different points in Frink’s career, across different media. We can see the breadth of her interests, from images of animals and insects, such as Carapace II (1963) to works on Christian religious themes, alongside figures from legend and history. Indeed, it is a striking feature of her work that she was so open to stories from such differing traditions. The show was put together from a large bequest to Yorkshire Sculpture Park from the artist’s late son, Lin Jammet. The exhibition in the Weston Gallery is accompanied by a display of Frink’s characteristic bronzes outside in the park itself. These are the life-size male figures for which Frink is most famous. Protomartyr (1976) has slender limbs, the figure’s arms half raised as he reaches his face skyward, his eyes closed in beatific calm. It is Saint Stephen who is often called the protomartyr or first martyr of Christianity (he died in c. AD 34). He is frequently depicted with a clutch of stones, alluding to his death by stoning. Nothing about this figure by Frink, however, suggests Stephen’s martyrdom. What did it feel like to be the first martyr? Transcendental, Frink seems to say. There is a marked difference between this work and Judas (1963), made more than 13 years earlier. While Protomartyr is smooth and sleek, Judas is clumpy and half-formed, with bulky shoulders and spindly legs. His head is helmet-like; his eyes are covered. Here – as in other works – figures with obscured eyes seem to symbolise some kind of ethical blindness.

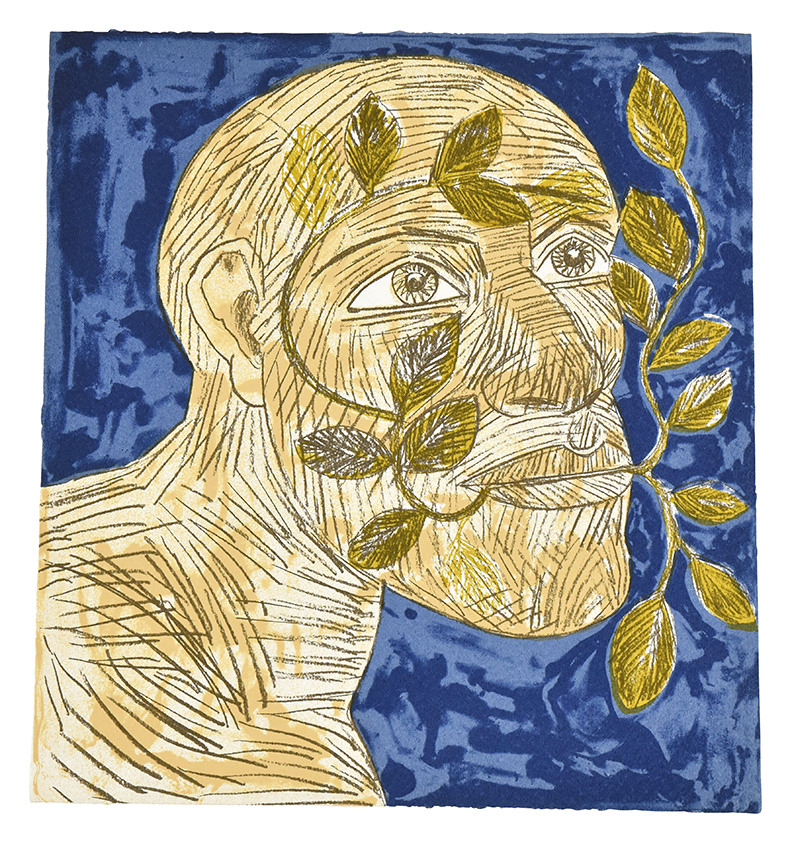

On my way home, I kept thinking about a plaster work called Green Man (1991) in the Weston Gallery. It’s a haunting piece, created after Frink had been diagnosed with a terminal illness. The Green Man, or the Woodwose, is an ancient English folkloric symbol of nature, fertility and renewal. Appearing carved into misericords and as a heraldic motif, and often composed of leaves, he is a creature of the woods, a bringer of chaos but also hope. Outwardly the form at Yorkshire Sculpture Park looks like a familiar Frink figure – big eyes, heavy chin, bald head. But up close, in the white plaster, you can see tendrils of greenery growing from his mouth and up over his head. This Green Man also appears in two screen prints from 1992. In both images the men cast their eyes towards the sky. The series was to be Frink’s last; she died in April 1993. In her final works, Frink reached back into the distant past to create images filled with quiet promise.

Green Man (blue) (1992), Elisabeth Frink. Photo: © Frink Estate; courtesy Yorkshire Sculpture Park

‘Elisabeth Frink: Natural Connection’ is at Yorkshire Sculpture Park until 23 February 2025.

From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze