In the mid 1950s Edgar Blake, an ageing director of the Fine Art Society in Bond Street, asked a new recruit to the firm: ‘If you don’t wear a hat, what do you take off when you meet a client in the street?’ Mr Blake’s father had been the Leggatt family coachman and the Leggatts had set him up in business in the 1920s as a print dealer in the City, but like many others he had been bankrupted in the wake of the Wall Street Crash. I joined the staff of the Fine Art Society as the front-desk dogsbody in 1961 and had, among other duties, to type Mr Blake’s letters, which he loved to sign off, especially when writing to titled clients, with phrases such as ‘Thank you my lord for your many favours.’ Today the lord is more likely to be the dealer emailing a client in the Middle or Far East than the landed recipient of such epistles.

The young recruit of the 1950s was Andrew McIntosh Patrick, whose vision played a major part in shaping the Fine Art Society’s policies from the mid 1960s until his retirement in 2004. Up until this point the gallery, apart from its annual spring show of early English watercolours, seldom held catalogued exhibitions, and the hang was traditional, though not quite as dense as it had been a few decades earlier. For the rest, the walls were hung with a mixture of Victorian and Edwardian paintings, interspersed with flower pieces by Cecil Kennedy and watercolours by William Russell Flint, plus the occasional Boudin or Fantin-Latour. The revamp of the mid ’60s swept away most of the then rather tired contemporary stable and moved the concentration firmly on to British work. The first year this took effect was in 1968, with shows devoted to Philip Wilson Steer, the New English Art Club and British sculpture 1850–1914, plus an exhibition of work by Edward Bawden, the first of the new wave of contemporary artists the gallery was to show.

A pre-war hang of prints and drawings at the Fine Art Society. Courtesy the Fine Art Society

Bawden, more modest than any art student, had been hesitant in making contact. ‘I am very delighted by chance I came along to see you,’ he wrote, responding to a letter from Andrew McIntosh Patrick setting out terms for the exhibition: ‘The Fine Art Society would undertake at their expense to print a catalogue, to print and distribute invitation cards and to arrange comprehensive advertising. [… ] Commission on all sales would be 33 1/3% and the artist would pay for mounting and framing of all of the pictures.’ Although the commission was raised later to 40 per cent these terms remained unchanged until the end of Bawden’s life. Due to his move from Great Bardfield and the death of his wife he did not have another exhibition until 1975, by which time I had taken on the responsibility of handling and promoting his work with the tricky task of raising his prices. Like many artists whose early career had been affected by the Wall Street Crash he had little faith in the fact that just because there was a sale today there would be another buyer tomorrow. Once persuaded, he wrote: ‘The matter of deciding prices is entirely in your hands – I have no wish to interfere.’ And again: ‘On your advice I looked in at the John Nash exhibition in Cork Street. His prices deserve admiration… 2 big Bawdens equal in price 1 small Nash.’

What is now generally termed ‘modern British’ art was still in the doldrums, critically and commercially. Nevinson’s A Dawn, which Sotheby’s sold recently for close to two million pounds, was sold by the same firm in the early 1960s for a mere £150. In the mid ’60s I bought for myself Stanley Spencer’s Leg of Mutton Nude, one of the masterpieces of 20th-century British painting, which cost me £1,500; when in 1974, with growing family responsibilities I needed to sell it, I gave it to Sotheby’s who declined to illustrate it in the catalogue for fear of being sued for sending pornographic images through the post. It fetched £8,500 and was purchased by the Tate who did not put it on show until the next Director’s Report came out with it reproduced as the frontispiece.

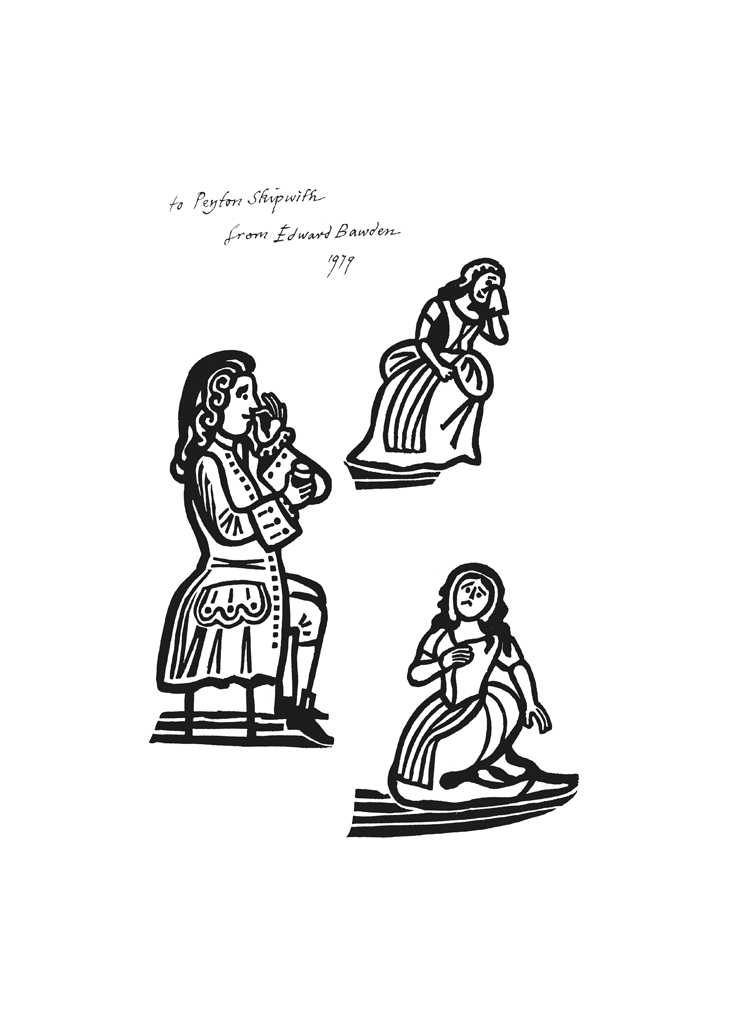

Frontispiece for Edward Bawden’s A Book of Cuts (1979), inscribed to Peyton Skipwith

Apart from cajoling Bawden to complete work for exhibitions, something he was always happy to put off, I had enormous pleasure over the years in encouraging other projects and commissions – the Bunyan tapestry for the Cecil Higgins Museum, Bedford; a map of the British Empire for Miami Dade Community College; the finishing and publication of Lady Filmy Fern, which won the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Francis Williams prize for illustration in 1982. And, of course, his final show in April 1987 with works purchased by both the Tate and the National Portrait Gallery. He used to send on to me letters to deal with, such as the one he referred to in December 1977 as ‘another hateful letter’, which was an offer from Duncan Robinson of an exhibition in the Rotunda Gallery at the Fitzwilliam. Our friendship and correspondence continued until his death and I was touched when he wrote ‘you must realize by keeping me busy & even selling some of my work you have extended my life by several years.’

It is now nearly 30 years since Bawden died and closer to 50 since I had to inch his prices over the hundred-pound threshold. His finest watercolours now fetch five-figure prices, publishers vie to reissue many of the books he illustrated, Dulwich Picture Gallery is devoting the summer months to a major exhibition of his work (23 May–9 September), as is the Fry Art Gallery, Saffron Walden (‘Edward Bawden at Home; A Working Life’, 1 April–28 October). And Neil Jennings is mounting an exhibition of Bawden and friends at Morley College, the site of Bawden’s first mural triumph, (18–23 June), while the popular ‘Ravilious & Co’ moves to its final venue, Compton Verney (17 March–10 June).

Dear Edward: Being the Correspondence between Peyton Skipwith & Edward Bawden, 1968–1989 is published by Hand & Eye Editions.

From the March issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)