‘You ain’t heard nothin’ yet,’ says Al Jolson’s character in The Jazz Singer (1927), the first feature film to contain dialogue spoken aloud. If film-curious audiences know one thing about The Jazz Singer, it’s that the movie ushered in ‘the talkies’ and signalled the end of the silent era. But for every great leap forward in cinema technology, there are other, more incremental developments. Try to identify the first colour film, for example, and you will probably find that it depends on your definition.

There are parallels here with the burgeoning world of extended reality (XR), which has yet to find its Jazz Singer. In a cinematic context, XR – a catch-all term that comprises virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR) – is a way of experiencing works that usually require wearing a headset which modulates the world around you. The degree of modulation depends on the form of XR: the world you see in AR is the real world, overlaid with digital components – characters, say, who might interact with each other. At the other end of the spectrum is VR, in which your headset presents you with an entirely virtual 360-degree world that is fully rendered whichever way you turn. After a while, you shake the impulse to spin around to see if the world behind you is still there.

XR in its current form has more in common with theatre, art installations and video games than with cinema. But for those curious about this hybrid art form, the ‘Expanded’ strand of the London Film Festival has been introducing it to audiences since 2020. XR may be in its infancy, but it’s developing fast: this year’s Expanded line-up was more ambitious than last year’s, with several installations requiring an entire room or lasting longer than 20 minutes. As with the cinema of a century ago, the shortcomings of the medium are often apparent: the graphics can be ropey, the more interactive elements often hokey. But just as the limitations of early cinema gave rise to examples of sublime artistry, the constraints of XR in its current form force artists to get creative.

Colored (Noire) (2023), an augmented-reality experience by Pierre-Alain Giraud, Stéphane Foenkinos, and Tania de Montaigne. Courtesy the artists

Take the AR work Colored (Noire), one of the more ambitious pieces at Expanded. A French-Taiwanese co-production, Colored aims to immerse the viewer in Alabama in 1955, alongside Claudette Colvin, the 15-year-old who refused to cede her bus seat to a white woman months before Rosa Parks did. The viewer is invited to sit on or walk around a set of benches, which take on different resonances when spectral set-dressings begin manifesting: as the outline of a bus shimmers into view around the seating area, the benches become bus seats for passengers both phantom (conjured by the headset) and real (the viewers). Later, the benches act as seats in a district courtroom, as we attend Colvin’s hearing in the weeks after her act of civil disobedience. Form matches content perfectly: the viewer’s inability to interact with the ghostly goings-on creates a horribly appropriate sense of passive spectatorship.

If cinema is, in the words of the critic Roger Ebert, an ‘empathy machine’, XR supercharges the empathy element, creating another dimension – literally – in which to identify with film characters. But the format can raise questions about the ethics of inserting audience members into recreated horrors. If Colored works because its XR adds an existential dimension to what is essentially an educational piece, in what other ways can XR deal with difficult subjects? Letters from Drancy, also showing at Expanded, provides one answer. It gestures at the impossibility of depicting the Holocaust by employing all manner of techniques – VR animation (both 2D and 3D), documentary and thriller elements. Unusually, there is a sort of real-life set dressing outside of the headset: handwritten postcards, purportedly from the 1940s, hang from the ceiling, as if conceding the inability of VR to handle the subject.

Letters from Drancy (2023), a VR Documentary by Darren Emerson. Courtesy the artist

Letters from Drancy captures the reckoning of Marion Deichmann, a real-life Holocaust survivor, with the death of her mother at Auschwitz. Remarkably detailed animated segments place you squarely in Deichmann’s shoes: at one point, you’re hiding in the back of the truck that conveyed mother and daughter to temporary safety in Paris, the breath visibly rising from your mouth. Such scenes – which, were it not for their quietude and restraint, would risk seeming exploitative – are intercut with documentary segments in which Deichmann, in her late 80s, walks the streets of modern-day Paris, with photography pointedly superimposed on present-day locations.

XR is remarkably well suited to this kind of time-slippage, so perhaps it’s no surprise that the two most historically-minded installations were the most memorable. Many of the other offerings seemed to touch on themes without using XR to give them new wrinkles. Things Fall Apart, for example, draws on Yeats’s poem ‘The Second Coming’ and largely consists of a rolling grid of unsettling AI-generated pictures – many in the manner of Goya and de Chirico – that you can pick out and magnify with your XR pointer. But nothing in the installation perturbs as much as the poem, and at a running time of 25 minutes, the piece is simply too long.

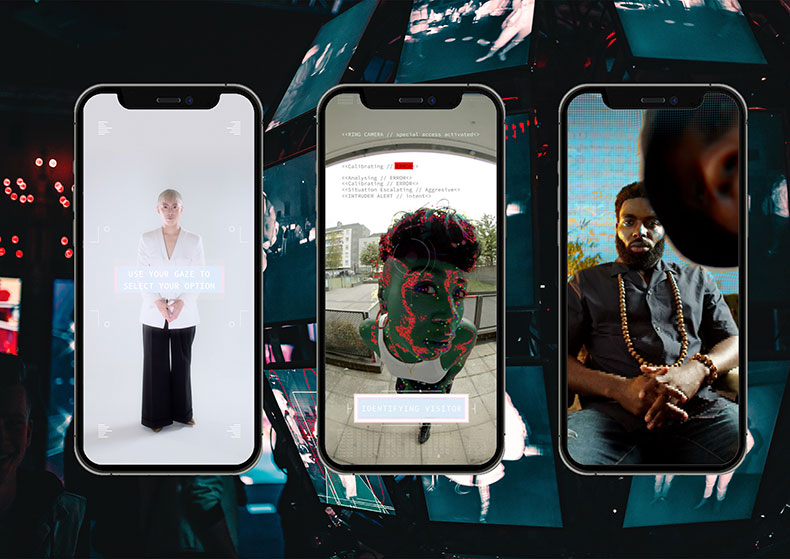

Consensus Gentium (2023), an XR experience by Karen Palmer. Courtesy the artist

It is telling that one of the more exciting works, Consensus Gentium, requires no headset. The interactive film takes place entirely on an iPhone and co-opts you as the user into an app named Global Citizen, which purports to measure your compliance by tracking your facial and eye movements. Though it doesn’t always seem certain of how much control it wants you to have over the film’s narrative, it’s a sharp exploration of contemporary concerns: the ease of surrendering personal data; the dangers of automated facial identification; the ability of AI, if given enough power, to restrict the social or even spatial mobility of citizens.

Consensus Gentium provides a playful glimpse of the power of XR exhibits to probe and provoke. It’s also a neat reminder of two things: that extended reality works best when what the artist has to say meshes precisely with the tools used to say it; and that these tools can take many forms. If the uneven but varied displays at the London Film Festival suggest one thing, it’s that we ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

*

The lead artists on ‘Colored (Noire)’ were Pierre-Alain Giraud, Stéphane Foenkinos and Tania de Montaigne; it was produced by Novaya and Flash Forward Ent. The lead artist on ‘Letters from Drancy’ was Darren Emerson; it was produced by Micaela Blitz. The lead artist on ‘Consensus Gentium’ was Karen Palmer; it was produced by Tom Millen, Thalia Mavros, Meg O’Connell and Tuyet Vân Huynh.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)