From the April 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The so-called ‘devil’s chord’ – a dissonant tone made by playing a chord with a flat top note, also known as the ‘flatted fifth’ – can sound ominous, haunting or deliciously wicked. This was how the musically gifted artist Gertrude Abercrombie described her paintings: ‘a little bit kind of offbeat […] or kind of way out there. Flatted fifth is what it is.’ Abercrombie’s twilit landscapes, spooky self-portraits and claustrophobic interiors from the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s are suffused with an eeriness that imprints itself on your memory. Yet her work is little known outside her home town of Chicago, and even there, for years she was best remembered as an odd lady who sold paintings at art fairs.

But Abercrombie was hardly an outsider artist à la Henry Darger. She was widely respected in the Chicago art world, hobnobbing with curators, artists, musicians and writers, and showing with prominent galleries in Chicago and New York. What happened, why was she forgotten? Enter this quietly stunning retrospective of her work at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, which, almost 50 years after her death, does more than give Abercrombie her due; it is also a much-needed reshuffling of the conventional hierarchy of mid-century American art.

Untitled (Lighthouse, Whale, and Black Sea) (1948), Gertrude Abercrombie (1909–77). Photo: Michael Tropea/Estate of Gertrude Abercrombie; courtesy Lincoln Glenn Gallery, New York

Abercrombie was an only child, born in 1909 to itinerant opera-singing parents. When she was young, her family lived in Berlin so her mother could study opera; the First World War drove the family back to the United States, and they eventually settled in the Hyde Park neighbourhood on the south side of Chicago, where Abercrombie remained for the rest of her life. In 1944, she, her husband and their two-year-old daughter, Dinah, moved to a large Victorian house. Though her personal life was full of upheaval, two things were constant: her love of jazz and her fierce attachment to Hyde Park. The area at the time was a bohemian enclave: it was interracial (the non-white population rose from 6.1 per cent to 36.7 per cent between 1950 and 1956) and tolerant of homosexuality at a time when people were being tried and convicted of ‘morality charges’. Abercrombie’s house was the site of renowned parties and jam sessions during which alcohol flowed freely and musicians played fervently, with Abercrombie sometimes joining on the piano. Trumpeter Clifford Brown wrote the song ‘Gertrude’s Bounce’ for her, and the Modern Jazz Quartet used her home as their Chicago base while touring for almost two years.

Abercrombie was staunchly anti-racist (she once listed an apartment in her house that required applicants with ‘no racial prejudice’) and her closest friends were gay. Jazz music was pervasive in her life, and deeply informed her painting: her close friend Dizzy Gillespie, who was in a position to know, called her ‘the bop artist’, saying that Abercrombie ‘has taken the essence of our music and transported it into another form of art’.

In some ways, Gillespie’s statement is mystifying. Jazz and bebop are strongly associated with both improvisation and complex rhythmic patterns, both of which suggest Abstract Expressionism as a visual manifestation (or else the syncopated abstraction of Mondrian’s 1943 Broadway Boogie-Woogie). Abercrombie’s figuration, however, couldn’t be further from AbEx styles. Yet her art was weird and unpredictable, with cryptic compositions and recurring themes, such as a tall female figure in a long dress, considered a stand-in for the artist herself, or cats, owls, dead trees. She called René Magritte her ‘spiritual daddy’ and made shadow boxes that were clearly inspired by Joseph Cornell. In that sense, Abercrombie’s work does have the feel of bop: it builds a world that you want to lose yourself in.

Where or When (Things Past) (1948), Gertrude Abercrombie (1909–77). Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Wisconsin. Photo: Paige Holzbauer; Estate of Gertrude Abercrombie

Though friends called her Queen Gertrude, Abercrombie also embraced the persona of a witch. The painting Where or When (Things Past) of 1948, which takes its name from a Rodgers and Hart song, features a tall woman in a floor-length red gown, holding a string in both hands, one end of which is attached to a small cat, and the other to a tall cone, which could be either a witch’s pointed hat or a spirit trumpet used by mediums to hear voices from other planes. The shape of the trumpet bell appears a year later in another painting, which she named for Dizzy Gillespie. His head and trumpet emerge from behind a barren white tree, while an owl rests on the sole patch of grass on the ground.

The Church (1938), Gertrude Abercrombie (1909–77). Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Photo: Edward C. Robison III; Estate of Gertrude Abercrombie

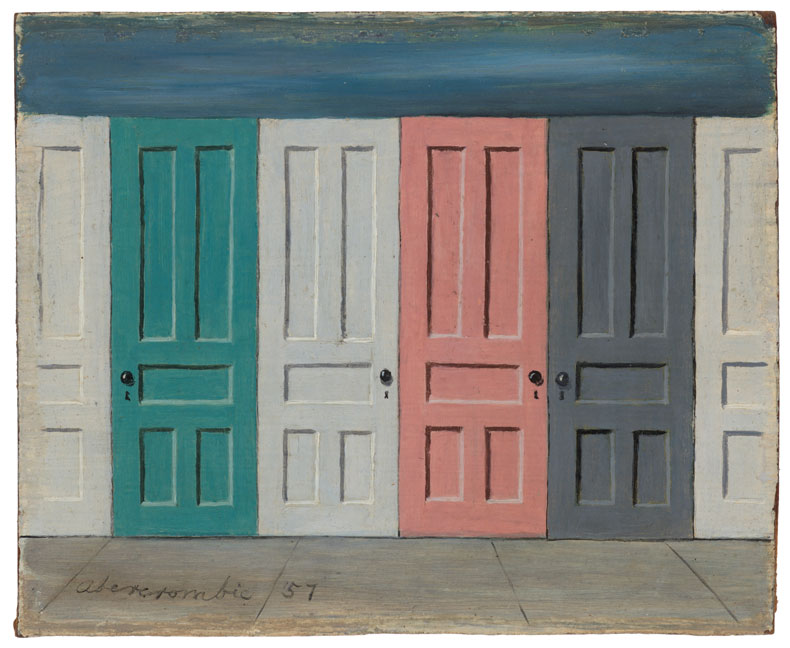

The tree, or one similar to it, appears in several other of Abercrombie’s landscapes. It is apparently based on one that she saw in western Illinois, in her father’s hometown of Aledo, where she spent much of her childhood. Such references are common in her work. Though Abercrombie’s paintings gesture at the supernatural, much of her subject matter was rooted in earthly reality. Her paintings reflect not only the Midwestern landscape but also its history: another recurring character is a bearded young man wearing a black top hat who resembles Abraham Lincoln, that famous one-time denizen of a log cabin in Springfield, Illinois. From the 1930s to the 1950s, Abercrombie primarily painted compositions referring to people and events in her own life. But the most profound use of reality in her work shows up in 1955, when she began a new series called Demolition Doors. In one respect, these paintings appear to be the closest Abercrombie came to approaching a modernist style: each painting features a row of nearly identical doors painted in primary colours. They are as stark and rigid as a Mondrian grid, yet they are a representation of a real event: the doors were used as fencing surrounding demolition and construction sites, as Hyde Park underwent redevelopment led by the University of Chicago that resulted in the overhaul of the neighborhood for the next decade. The not-so-secret reason for the renewal project was racially motivated: in private the university chancellor Lawrence A. Kimpton confessed that the new construction was a means of ‘cutting down [the] number of Negroes’ in Hyde Park. For Abercrombie, the impact was devastating. ‘It’s so sad I can’t even look,’ she wrote to friends. ‘But the doors are gorgeous.’

Doors (1957), Gertrude Abercrombie (1909–77), oil on masonite. Private collection. Photo: Julia Featheringill; Estate of Gertrude Abercrombie

Abercrombie’s life was by turns raucous, jubilant and painful. She lived through the shift from the liberated 1930s and ’40s to the reactionary, conservative post-war period. She saw her home town begin to thrive as an inclusive community, only to see that collapse under the force of capital and power. Her work reflects these eras, but has long been relegated to the margins of the narrative of mid-century American art. Now, perhaps, we are beginning to hear a new version of that story.

Letter from Karl (1940), Gertrude Abercrombie (1909–77). Union League Club of Chicago. Photo: Estate of Gertrude Abercrombie

‘Gertrude Abercrombie: The Whole World is a Mystery’ is at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, until 1 June.

From the April 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze