‘Gladiators of Britain’, a small and skilfully packaged collaborative touring exhibition, combines a few finds of genuine interest and importance with a lot of contextual material, most of it tailored towards a family audience: a build-your-own wooden Colosseum, helmets to try on and short swords to try out, tasteful screen-printed watercolours of Thracian warriors, net-fighters and the rest. There are also several videos of ‘blokes explaining things’, as my companion rather testily put it.

The chief purpose of the exhibition is seemingly to demonstrate that yes, there was a culture of gladiatorial combat in Britain; and that it was as cosmopolitan as any other aspect of the Roman world. Dorchester is one of a handful of British towns where some sort of amphitheatre has been identified (at a retrofitted neolithic site near the station called Maumbury Rings); the show is travelling on to Chester and Carlisle, which both had arenas, and to Northampton, which sat on Watling Street and was near the site of several forts. The most beautiful object on display is the Colchester Vase, a blackened ceramic urn showing four named fighters: one of those fighters was a veteran of a legion based in Germania, while another has a name that suggests African heritage. Elsewhere, an information panel reveals that a skeleton unearthed in York shows signs of its previous owner having been bitten by a lion.

Ceramic cremation vessel known as the Colchester Vase, decorated with a gladiator fight between a secutor and a retiarius, 2nd century AD, Colchester. Photo: © Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service – Colchester Collection

The show sets out some of the paradoxes inherent in the Roman custom of treating ritualised armed combat as entertainment, but it doesn’t really try to get to grips with the question of what the arena meant to the Romans – nor the perhaps knottier question of what it might mean to us. Partly this is to do with uncertainty. We have countless references to gladiatorial combat, animal hunts, staged naval battles and the like in the sources, from Livy and Plutarch on Spartacus, via Commodus – the bad guy in the first Ridley Scott film – taking potshots at a rhinoceros from the safety of an elevated platform, to Augustine bemoaning the fatal hold the arena came to have on his friend Alypius. There is also a growing hoard of material evidence. What we don’t have, and probably never will, is a sense of balance: how many gladiators were slaves and how many chose the life willingly, as a path to fame and fortune? What proportion of bouts ended in death? If you’d gone to the trouble and expense of trapping a tiger and schlepping it back to Rome, would you really let some idiot spear it straight away? How many Christians were really killed in the arena?

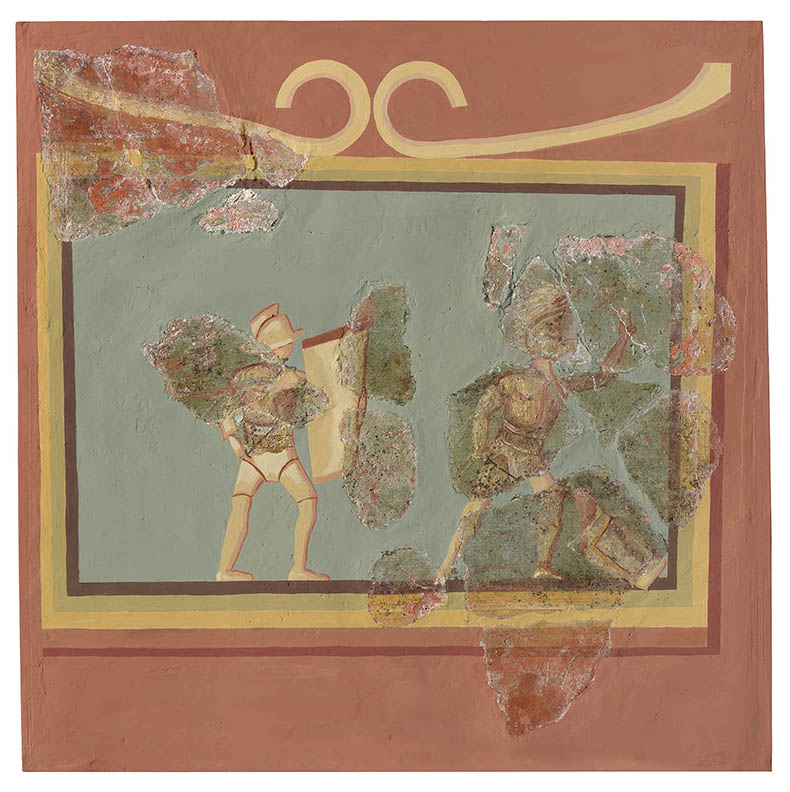

Reconstructed wall painting depicting combat between two gladiators, 1st century AD, Colchester. Photo: © Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service – Colchester Collection

What is clear is that gladiatorial combat lay at the heart of Roman culture for several centuries and that the games, wherever they took place, were documents of civilisation as well as of barbarism, to adapt Walter Benjamin’s phrase. A day at the arena might begin with the reading of proclamations and the punishment of criminals. The amphitheatre was a mirror of the Roman world that brought the periphery – captives from conquered nations, religious dissidents, tigers – symbolically into the centre. A losing fighter would be more likely to leave the arena on foot if he were seen to have assimilated what were thought of as ‘Roman’ qualities: bravery in combat; stoical resignation in defeat. Analogies with modern sporting heroes suggest themselves rather too readily, in the prevalence of gladiator-related graffiti at Pompeii, for example, or the many references to fighters’ masculine mystique. But something often gets lost in translation: something to do with fate, power and freedom (it’s worth remembering that slavery was a political sanction), not to mention a note of irony or even camp that’s evident in the often outlandish costumes gladiators wore.

We ended our day with a craft lager at the Duchess of Cornwall in Poundbury, a bleak neoclassical township on the edge of Dorchester willed into existence in the 1990s by the future king. Charles’s love of antiquity has not so far extended to the construction of an amphitheatre, though there is a garden centre and a Waitrose. But arguably we have become so skilled at creating simulations or simulacra of violence – in sport, in cinema, in gaming, even in the unrelenting verbal fisticuffs of reality TV – that a taste of the real thing would not seem excessive so much as otiose.

Bone figurine depicting a gladiator of the murmillo class, 1st–2nd century AD, Colchester. Photo: © 2024 The Trustees of the British Museum

‘Gladiators of Britain’ is at Dorset Museum & Art Gallery until 11 May.

Bringing Pompeii back to life

Bringing Pompeii back to life

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze