In South Africa, the design of wine farms and estates can be every bit as varied as the wines they produce. Even historic estates from the 18th century have been reworked and remade for contemporary visitors and consumers.

The Stellenbosch region, around 50km east of Cape Town, features some of the oldest vineyards in the country. One of the first wineries here was the Hazendal estate, which began as a cattle-and-grain farm in 1699 before becoming the first wine producer in the Bottelary Hills in 1870. In an attempt to honour its history while remaining contemporary, the estate has begun commissioning artists to design its labels; it has chosen the South African artist Athi-Patra Ruga (b. 1984) to create the inaugural label for its Artists’ Series of sparkling wines.

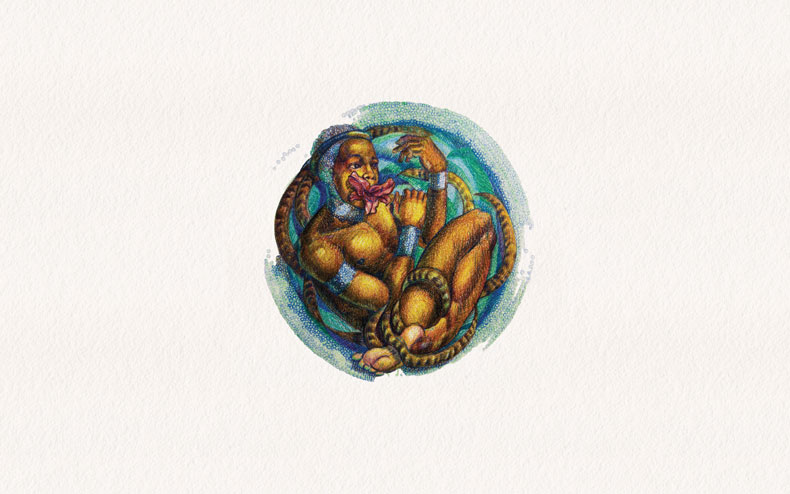

A bottle from the Artists’ Series of Hazendal MCC wines, with a label designed by Athi-Patra Ruga in 2025. Courtesy Hazendal Wine Estate

The label will appear on a limited edition of the Hazendal MCC (Méthode Cap Classique) – South Africa’s term for sparkling wine made in the traditional Champagne method, involving a second fermentation in the bottle to create natural bubbles. Ruga, best known for exploring the imagery of dreams and myths through a wide range of media, including costume and video works, represented South Africa in the Venice Biennale in 2013; his label design foregrounds the motifs of dance and performance that recur in his work.

The MCC artist label is part of a wider cultural programme that the Hazendal estate inaugurated with the Hazendal Festival in 2024, which aimed to bring together visual and performing arts. These initiatives were overseen by Khanyisile Mbongwa, the founding curator of the Stellenbosch Triennale and the curator of the Liverpool Biennial in 2023. ‘Working outside of the gallery frame on a wine farm,’ she tells me, ‘creates another dimension of imagination and creation for artists: you are now having to work with this openness, this never-ending horizon, and we can create possibilities from this expansive thing.’

The ‘Soil Edition’ of the Hazendal Festival, October 2024. Photo: Kaylin Petersen; courtesy Hazendal

In keeping with Ruga’s practice of using avatars to satirise and interrogate social hierarchies, the central figure is a nude muscular male caught in a state of metamorphosis, ‘unfurling’ as a flower emerges from his mouth. Drawing inspiration from the theatrical ‘death drop’ of voguing culture, which originated in the ballrooms of New York in the 1980s, the composition articulates a pluralistic and aspirational vision of freedom, refracted through the lens of a champagne glass. The image of this ‘gestational’ figure came to the artist as he was sipping the wine: ‘after a few sips the image of this figure unfurling, about to do a dance, a dance of light, [appeared] … in the past we have been dancing in spite of many things.’

This part of the Cape Winelands is celebrated for its rolling vineyards, granite-rich soils and maritime-influenced climate – ideal for producing balanced, characterful wines. Stellenbosch itself is at the heart of South Africa’s wine heritage, but as Mbongwa puts it, ‘it is quite a burdened and layered space historically.’ She selected Ruga for the festival and the label project because he is an artist ‘who can think on multiple levels and layers, who can think from an Indigenous, social and spiritual perspective while creating something that will sit within the arts and wine.’

Athi-Patra Ruga in 2018. Photo: Hayden Phipps; courtesy Hazendal

For Ruga, dance and spirits are culturally connected to drinking and ritual. ‘I’m Xhosa, from the Eastern Cape,’ he says. ‘Aunties, when they come to these traditional ceremonies, will bring MCCs as libations.’ He points out that rituals, ‘like a good MCC, seem very simple but are complicated and layered’. This applies to the bottle design, which ‘speaks of where I am from. The beautiful thing about Hazendal, of course, is its renewal, and now, like 30 years later, walking or jogging or just experiencing it doesn’t give me the same heaviness of the old world: I am a product of the new South Africa more than I am of the old one.’ He feels comfortable with the arts and cultural programme ‘because the art connection is coming with new voices’.

Mbongwa puts it most fittingly: she calls it ‘a choreography of histories’.

Athi-Patra Ruga’s design for a bottle from the Artists’ Series of Hazendal MCC wines (2025). Courtesy Hazendal Wine Estate; © the artist

French winemaking with a South African twist

French winemaking with a South African twist

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)