In 1962, Latif Al Ani, two years into his stint as lead photographer for Iraq’s Ministry of Information and Guidance, turned his camera to a familiar subject: Jewad Selim’s majestic Monument of Freedom, which spans Baghdad’s central Tahrir Square. Just a short walk from the Tigris river, Selim’s 50-metre-wide bas-relief had been completed in 1959, and became Iraq’s first piece of public art, commissioned by the new military regime to celebrate the recent revolution.

For Iraqis driving around the Tahrir Square roundabout, the energetic figures dancing across the white stone must have seemed at once familiar and defiantly celebratory. Selim’s signature style, a synthesis of ancient Babylonian and Sumerian forms and modern figural abstraction, charged the region’s classical iconography with ideas of adversity, resistance, and solidarity. In Al Ani’s meticulously framed black-and-white photograph, the tremendous frieze diagonally spans the centre of the image, its hefty trapezoidal supports grounding it on both left and right. Beneath the monument, a stylish woman in a patterned dress strolls away from the camera, one high heel blurred in mid-step. In highlighting Selim’s sculpture, Al Ani takes the sculptor’s ideas one step further and grounds them in reality – the emblematic figures above and the woman below share a common heritage, but with this photograph, the woman, frozen in the early 1960s, is transformed into as much of a symbol as the sculpted dancers.

Tahrir Square, Baghdad (1962), Latif Al Ani. Image © the artist and the Arab Image Foundation;

courtesy the Ruya Foundation

Tahrir Square, Baghdad is one of the most layered and quietly compelling images in the current exhibition of Al Ani’s photographs at Coningsby Gallery, London. Over 50 black-and-white works, punctuated with a few sumptuous colour prints, have been brought together by the Ruya Foundation for Al Ani’s first UK exhibition. The images, taken from the photographer’s personal archive, span from the 1950s to the ’70s, and provide a detailed, modern picture of mid-century Iraq that may surprise and enlighten a London audience more familiar with present-day news imagery from the region.

In recent years, Al Ani’s national reputation as the founding father of Iraqi photography has grown globally, with the help of the Ruya Foundation. The only non-profit in Iraq working with contemporary artists, the foundation included Al Ani in its Pavilion of Iraq at the 56th Venice Bienniale in 2015, reigniting interest in his long-buried archive. An elegant, award-winning monograph published earlier this year by Hatje Cantz brought further recognition, and includes a frank and illustrative conversation between Al Ani and Ruya chair and co-founder Tamara Chalabi. ‘I wanted to show our heritage against our present, the contrast between the past and present, where we had arrived in comparison with the past,’ he says early in the interview, ruminating on his career photographing a swiftly changing society. ‘The fear that I had is what we are living today.’

Building the Darbandikhan Dam (1962), Latif Al Ani. Image © the artist and the Arab Image Foundation; courtesy the Ruya Foundation

Al Ani, who still lives in Baghdad, trained as a professional photographer while on the job for the Iraq Petroleum Company in the 1950s. There, he was charged with documenting the company’s projects on the ground and from the air, taking these straightforward advertising assignments as an opportunity to experiment with form. In 1960, he founded the photography department at the Ministry of Information and Guidance, creating a vast archive of social, architectural, and heritage imagery for, among other governmental projects, New Iraq magazine – the entirety of which was destroyed during the US invasion of Iraq in 2003.

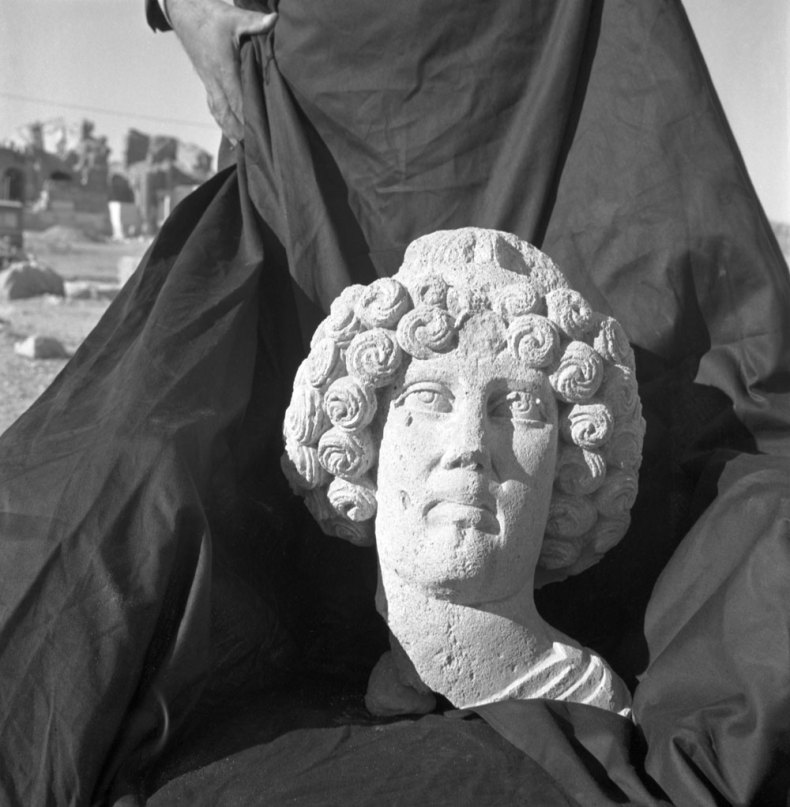

The breadth of subject matter within Al Ani’s work is astonishing: photographs of native antiquity, such as Stolen head that was not retrieved, Hatra (c. 1960s) drive home his commitment to displaying heritage in a contemporary context, while Al Aqida High School, Baghdad, taken in 1961, is a joyful depiction of schoolgirls enjoying some leisure time. Playing again with the diagonal lines which so often zig and zag through the centre of his images, Al Ani frames the young women and their hoops to create a graphic funnel, as a suited schoolmistress observes them seriously in the background, hands firmly on both hips.

Al Aqida, High School, Baghdad (1961), Latif Al Ani. Image © the artist and the Arab Image Foundation; courtesy the Ruya Foundation

The images on display also oscillate between grand architectural studies and intimate portraits of people, often going about their daily business, or touring heritage sites. An aerial photograph of the Mirjan Mosque from 1962 transforms the religious structure into a mass of brilliantly white volumes, solidly maintaining their presence among a mess of arbitrarily parked cars. Keen to include images from Al Ani’s many trips abroad, the exhibition’s curators took deliberate care to hang photographs of window shoppers in Berlin next to picnickers in Baghdad, highlighting cultural similarities between societies so often depicted as at odds with one another.

Stolen head that was not retrieved, Hatra (c. 1960s), Latif Al Ani. Image © the artist and the Arab Image Foundation; courtesy the Ruya Foundation

Over time, Al Ani’s assignments became increasingly fraught with nationalistic agendas. Towards the end of his career, the Ba’athists and Saddam Hussein’s regime began exercising more and more control over artistic and cultural narratives of the country; when the Iran-Iraq War broke out in 1980, restrictions forced Al Ani to stop photographing altogether.

Selim’s Monument of Freedom still stands in Tahrir Square, just where Al Ani photographed it nearly 60 years ago, a witness to the changes authoritarian Arab nationalism has wrought on the Middle East, and the successive conflicts and occupations that wiped away the modern Iraq of Al Ani’s universal images. Today, his photographs hold a weight that far exceeds their formal beauty. ‘The past is mine, not the future,’ he says. ‘That is for others. The images will be more important in the future, as they show a vanished world. […] It’s not sentimentality, it’s a fact, and it’s depressing. It is counter-intuitive; things are meant to progress forwards, not backwards.’

‘Latif Al Ani’, presented by the Ruya Foundation, is at the Coningsby Gallery, London, until 16 December 2017.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)