The painter and printmaker Tammy Nguyen takes an unabashedly intellectual approach to her work. Drawing on Dante’s Divine Comedy and incorporating references to 20th-century South East Asian politics, as well as throwing in the occasional Tyrannosaurus rex for good measure, she realises her premeditated designs on canvas with painstaking precision, though she leaves her work open to more instinctive flourishes too – splashes of red, say, that resemble marbles, moons or eyes. An assistant professor of art at Wesleyan University, specialising in printmaking and book art, Nguyen developed an expertise in illustrated manuscripts early in her career – an interest that has found expression in her mixed-media sculptures. She also publishes artist books through her imprint Passenger Pigeon Press. Her exhibition ‘A Comedy for Mortals: Purgatorio’ is at Lehmann Maupin, London, until 20 April. It is the second in a series of three Dante-inspired exhibitions by Nguyen; the final show in the series, ‘A Comedy for Mortals: Paradiso’, will open at Lehmann Maupin, New York, next year.

Installation view of ‘A Comedy for Mortals: Purgatorio’ by Tammy Nguyen at Lehmann Maupin, London. Photo: Eva Herzog; © the artist

Where is your studio?

In a little town called Easton, Connecticut. I have a three-acre property there – a little brown house where my family lives and, about 200 steps away, a really nice red barn that is my studio. My husband and I moved there three years ago – I was a new mom, I’d just been appointed as an assistant professor and there was the pandemic, so there were a lot of life changes going on.

What’s the atmosphere like in your studio?

It’s beautiful. There’s so much nature where I live. In Connecticut you have four real seasons. In the autumn, the leaves are oozing with red and orange; in summer, it’s extraordinary – lush and humid; in the spring, the blossoms are just bursting; and when we get a good winter, everything’s just covered in the most beautiful untouched snow. And I see all that through the windows of my barn.

It’s a space that’s always welcome to people. My three-year-old comes running in from the house all the time, and she’s just a delight. She tramples all over the place.

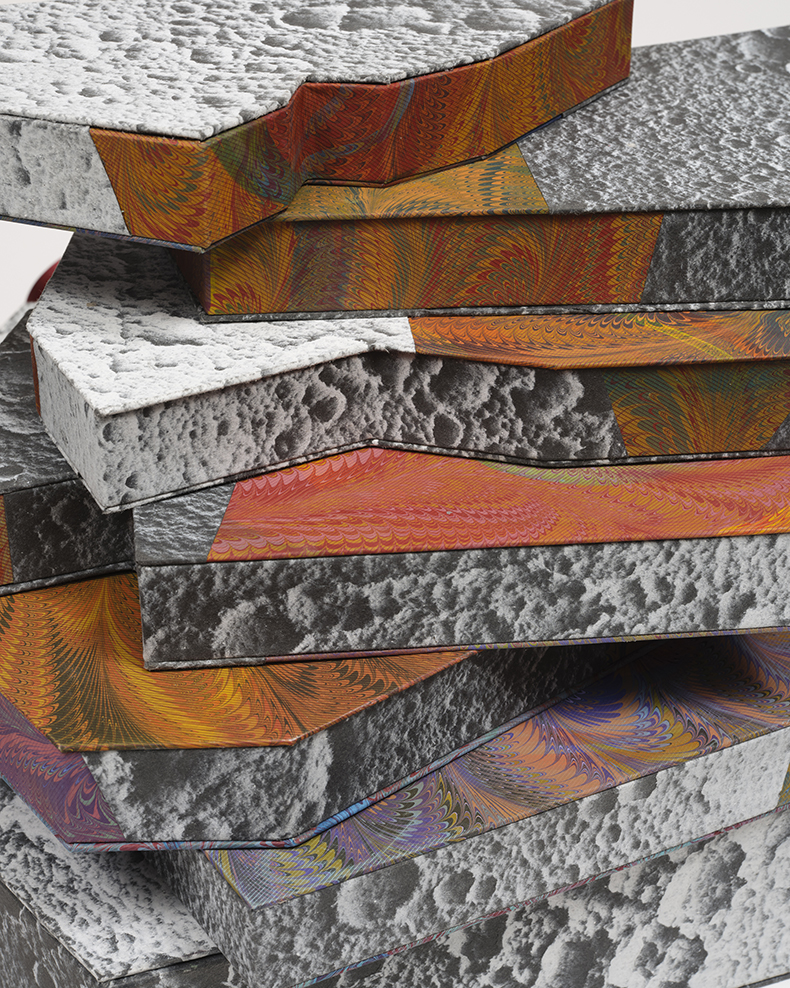

Spears Pointed (2023), Tammy Nguyen. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul and London; © the artist

What do you tend to listen to in the studio?

I get a lot of cool ideas from the New Books Network. It’s a series of podcasts comprising interviews with academics about their books, which cover all sorts of areas – military history, critical studies, the environment. My favourites are the new books on religion.

As for music, my assistant Holly just showed me this new app called Radiooooo. You pick a country and a decade, and it plays the radio of that time period. It’s amazing. The music that was playing in the last few days of preparing this Lehmann Maupin exhibition was from Antigua in 1970. I had really wanted to visit the country but that’s not going to happen anymore – at least, not for a while.

Classical music has also been a big thing. I’m preparing to get deep into my next exhibition after this show. It has a lot to do with music, so I’ve just been going through different composers: Rachmaninov, Bach’s ‘Inventions’, a couple of Beethoven concertos that I’ve been curious about. As I’m in London for this show, I went to see the opera The Flying Dutchman the other night – I like Wagner a lot, I think he’s a very clear, crisp composer.

And, of course, there is the indulgence of pop music.

How does music inform your work?

I have a desire to create a show about contradiction. I’m planning an exhibition with haikus at its heart: haikus follow a five-seven-five syllable structure, which gives you 17 syllables, and I want those to be transformed into 16 notes of music. So with two bars of music in 4/4, a question arises: how do you hide the extra note? How that will take shape visually may be the crux of my upcoming exhibition at the Sarasota Museum of Art in Florida.

Long Live and Prosper (2023), Tammy Nguyen. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul and London; © the artist

What do you like most – and least – about your studio?

There’s no bathroom. We have to get some plumbing out there. That’s the only thing I dislike about my studio, which means that it will become perfect.

How large is your studio team?

Holly is my main gal right now – she’s my one permanent team member, but I’m pretty sure we’ll be expanding soon. Then there’s a lot of other people who come and go, who are all former students from my printmaking classes.

For this Lehmann Maupin exhibition, there was an amazing group of people who did a lot of the hand-set type. They helped with all the ‘sous-cheffing’ – the cutting of the paper, the rolling up of the ink, the stretching of the paper. There’s a lot of that kind of work to be done for one of these shows.

Do you have a studio routine?

I wake up at 5.30am, make myself a coffee and start writing. There are a lot of ideas that I want to express in writing, and it’s also the time I’ll write the introductory essays for the artist books I publish through my imprint, Passenger Pigeon Press. Two hours later, I’ll do a lot of my emailing, which is pretty quick, and then I make a to-do list.

I also make a list of ‘moves’ I’m going to make in my paintings. Because they’re all made on paper using water-based materials, much like in the traditions of East Asian painting, there are no take-backs. So say it’s foliage day: I would have done a lot of observational drawings of the plants already. I’ll think, ‘today we’ll do mid-tones of small leaves’, and I’ll write that down as a move. Then I might write ‘blue stem’. I’m not loyal to this list, but I think it through almost like how I imagine an athlete might think about the plays they’re going to make.

Once that’s done, I pack my daughter’s lunch, go for a run, and when I come back I dress her and drive her to school. By the time I get back, it’s 9.30am; Holly comes at 10am. If we have a lot of catching up to do, we’ll just go over deadlines and things that need to get done.

Then I paint until 6pm, head back to the brown house and make dinner.

Mine, Purgatory (2023–24; detail), Tammy Nguyen. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul and London; © the artist

What are the most unusual objects in your studio?

For this show, there are a lot of dead moths in my studio. I’ve got three species: a Malaysian one, an Indian one and a Chinese one. I was able to get both the male and the female of the Chinese species; the male is blue and the female is pink, which is funny. I was drawing them for a long time. In previous projects, I was thinking of how to collapse the micro and the macro; grasshoppers informed the recurring theme of little helicopters in my work. I also have a box of random insects.

The other cool thing I have in my studio is fern fossils. I found a guy in Pennsylvania who sells these awesome fossilised ferns, and I was drawing those from observation too.

I try to surround myself with materials. I think that observational drawing is part of every studio’s healthy diet. I try to embed that into the practice as much as I can, but I should do more.

What is the most well-thumbed book in your studio?

Probably Dante’s Purgatorio. I use the Stanley Lombardo translation (from 2016). I find him to be very lyrical, and it helps when someone’s lyrical when translating old texts, because, my god, it’s so hard!

Three Crown of Thorns (2023), Tammy Nguyen. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul and London; © the artist

Who is the most interesting visitor you’ve ever had?

Shortly after my show at the Berlin Biennale in 2022, a priest named Buddy Gharring reached out to me. He’s from Twin Falls, Idaho, which conceptually is even further away from me than London. He wanted to use my work as a backdrop for his sermon. I couldn’t believe it – as an artist, you always have this dream about reaching people but, more often than not, your work is mostly being viewed by people in the art world. But there was this Christian magazine that wrote about my work, and Buddy saw an image of my art and messaged me on Instagram.

I was delighted. I understand the ways in which religion, and certainly Christianity, can be criticised – I went to Catholic school; there are a million things to complain about. My family’s not Catholic and neither am I, but there’s a contradiction for people of Vietnamese heritage in having a faith that was brought to you through a colonial campaign that caused a lot of pain and erasure, but at the same time has given you a community and offered you salvation. It’s a very important part of one’s life if one has that faith, and I love religion for that – it offers so much for people and is so important to folks who need that in their lives.

As told to Arjun Sajip.

‘A Comedy for Mortals: Purgatorio’ is at Lehmann Maupin, London, until 20 April.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)