From the June 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Does the Venice Biennale affect the art market? The consensus on this non-commercial festival, which opened in April, is usually yes. In the va-va-voom 2000s it was common to see collectors snapping up works by Venice stars as soon as they could at Art Basel (for years the Venice preview ended two days before the opening of the fair). ‘See in Venice, buy in Basel’ became an often-repeated phrase.

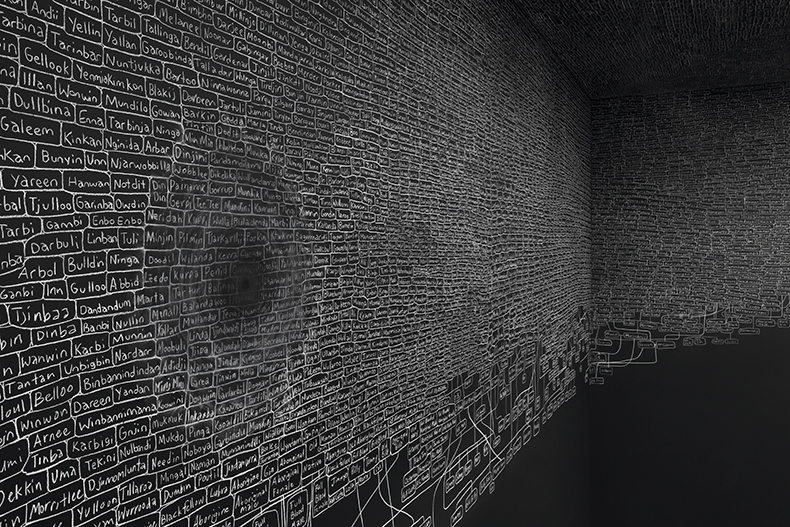

If the conventional wisdom holds true, this year should be a good one for Indigenous artists – those who trace their ancestries to the first inhabitants of countries such as Canada, Australia, Brazil and Norway. The winner of the Golden Lion for the best national pavilion, Archie Moore, is of Kamilaroi/Bigambul heritage. His stark, black and white installation in the Australian pavilion is a memorial to the 60,000-year history of his Aboriginal ancestors. Indigenous artists Jeffrey Gibson, Inuuteq Storch and Glicéria Tupinambá also represented the United States, Denmark and Brazil respectively.

The main International Art Exhibition, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, was similarly filled with work by Indigenous artists, including father and son Colombian/Nonuya painters Abel Rodríguez and Aycoobo, and the Native American artists Kay WalkingStick and Emmi Whitehorse. The Golden Lion for best work went to four Maori women artists, the Mataaho Collective, for a minimalist installation made from polyester hi-vis cargo straps.

This is not a new phenomenon. Some Indigenous artists achieved worldwide fame decades ago, particularly Australians such as Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri and Emily Kame Kngwarreye, who will have a retrospective at Tate Modern next year. Tjapaltjarri holds the auction record for a work by an Australian Aboriginal artist for Warlugulong (1977), which sold in 2007 at Sotheby’s to the National Gallery of Australia for A$2.4m. The record for a female Australian artist was achieved by Kngwarreye’s work Earth’s Creation (1994), which sold in 2017 for A$2.1m at Sydney auction house Cooee Art Leven. Her work was also included in Gagosian’s ‘Desert Painters of Australia’ exhibitions in New York and Los Angeles in 2019.

Installation view of ‘kith and kin’ (2024) by Archie Moore in Australia’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 2024. Photo: Andrea Rossetti; courtesy the artist/The Commercial; © the artist

Most Indigenous artists are much less well known. But they were a focus of curator Adam Szymczyk’s edition of Documenta 14 in 2017, which included work by Canadian/Kwakwaka’wakw artist Beau Dick and the Sami Artist Group. More recently, the huge international survey ‘Indigenous Histories’ opened last year at the Museum of Art of São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP), of which Pedrosa is artistic director. It is now at KODE in Bergen (until 25 August).

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes based in Montana, had the first solo retrospective of a Native American artist in the 93-year history of the Whitney Museum in New York last year (see May 2023 issue of Apollo). She mounted her own exhibition of contemporary Native American artists at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., ‘The Land Carries our Ancestors’, the first at the museum in 70 years. It is now at the New Britain Museum of American Art in Connecticut (until 15 September).

‘There’s definitely momentum at the moment,’ says Candice Hopkins, a Canadian-born curator and citizen of the Carcross/Tagish First Nation. She directs the Forge Project in upstate New York, which supports Native American arts and artists by buying work and lending them out. Hopkins credits exhibitions such as the Venice Biennale and Documenta 14 for driving change. ‘Documenta was the biggest, most sustained platform that a lot of Indigenous artists had ever had,’ she says. ‘Venice is also introducing a lot of artists and voices that aren’t broadly known.’

The Tate began collecting the work of Indigenous artists around a decade ago, but Hopkins says that New York has only begun to catch up in the past five years. ‘We usually understand the art world as an ecosystem of curators, critics, art historians, collectors and galleries,’ she says. ‘But most Native artists I have worked with have had marginal [commercial] representation or none at all.’

Even artists who have found success in the biggest and most competitive art market – the United States – say they have faced tough times. Jeffrey Gibson, a Mississippi Choctaw-Cherokee painter, sculptor and film-maker, is the first Native American to represent his country in Venice. He studied at two of the world’s best art schools, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Royal College of Art in London, but by 2011 was considering quitting. ‘It all had to do with homophobia, racism and classism, specifically in the art world, and how challenging it was for me to engage in it,’ he says. At the same time, he was meeting traditional makers in states such as Oklahoma, Oregon and South Dakota. This led to a breakthrough phase of work, including a series of patterned, beaded boxing punchbags. ‘I realised all these people making their own clothes, music and quilts was a way of removing themselves from the mass culture,’ he says.

Gibson is now represented by three commercial galleries, including Stephen Friedman. The gallery declined to comment, but there is little doubt that Gibson’s market has grown since the dark days of 2011. At Frieze London in 2022 the gallery reportedly sold his works for between $135,000 and $300,000.

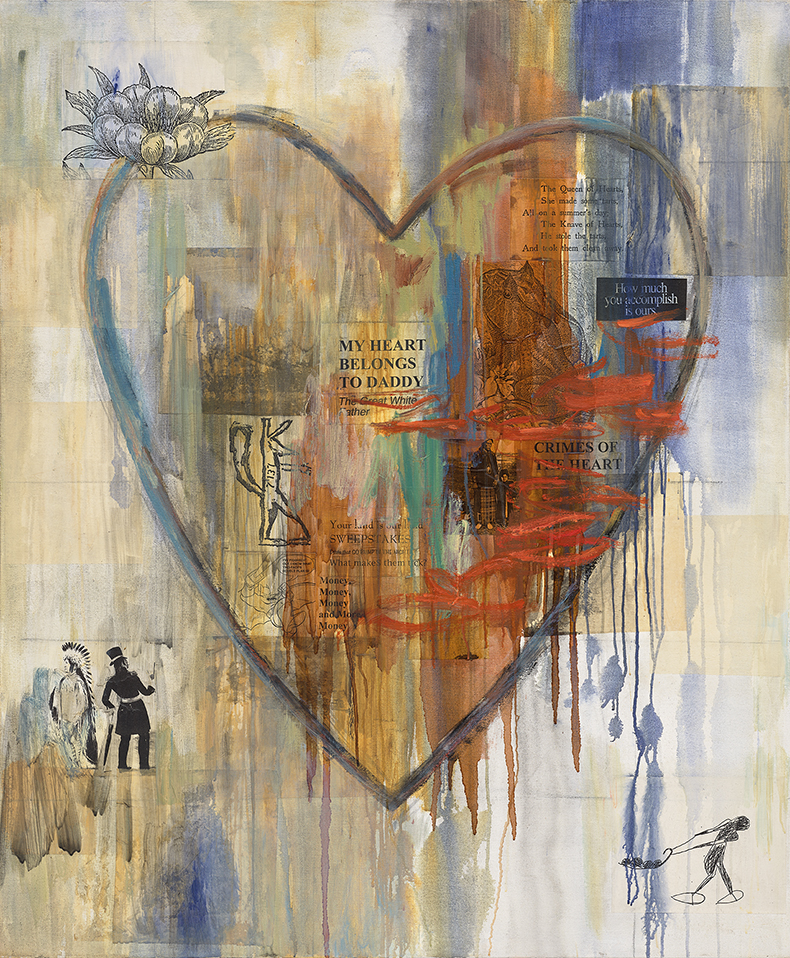

My Heart Belongs to Daddy (1998), Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. Courtesy Phillips; © the artist

‘The sky’s the limit for Gibson,’ says Los Angeles-based Native American art expert James Trotta-Bono. Earlier this year, Trotta-Bono was one of the advisors for ‘New Terrains’, a selling exhibition by auction house Phillips in New York. It included work by almost 70 artists from the 20th and 21st centuries, with prices ranging from $5,000 to close to $1m.

Trotta-Bono says the market for modern and contemporary work revolves around overlapping groups of artists. The earliest are those associated with the ‘studio school’ style of painting, founded in 1932 at the Sante Fe Indian School and with Bacone College in Muskogee, Oklahoma. Artists from this period painted in a flat, colourful style, drawing from Indigenous traditions and include Awa Tsireh and Narciso Abeyta (or Ha So De) from the south-west and Woody Crumbo and Solomon McCombs from Oklahoma.

Transitional post-war artists such as Oscar Howe and George Morrison fused their Native heritage with modernism, and paved the way for the founding of the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe. It fostered a new generation of contemporary Native artists such as Fritz Scholder and T.C. Cannon. Then there are more recent artists, such as Quick-to-See Smith, WalkingStick and Whitehorse, and younger artists such as Nicholas Galanin, Cannupa Hanska Luger, Melissa Cody and Rose B. Simpson.

Trotta-Bono says the markets for all three groups are rising, driven in part by large US institutions. ‘There is a rethinking of the American art story through a more inclusive lens, and many institutions are either doing their part or starting to catch up,’ he says.

Garth Greenan founded his New York contemporary art gallery in New York just over a decade ago, and has developed a reputation for championing under-recognised artists, including Native Americans. ‘It was only a matter of time – you can’t expand the canon of American art history without including all Americans,’ he says.

African American artists have seen a huge surge in curatorial interest in the past decade, but it is only recently that similar attention is being paid to Native artists. Why this should be the case is unclear. It may reflect the relative size of the populations: according to the US Census Bureau, around seven million people identify as having Native American heritage, one-sixth the size of the Black population.

Historically, many were forcibly relocated from eastern states: half the population lives in Oklahoma, Arizona, California, New Mexico and Texas. ‘There’s certainly been a degree of invisibility on the East Coast,’ Greenan says. ‘It was shocking how difficult it was to get people to pay attention when I started. But fortunately I had a core group of regular clients who believed in what I was doing.’

Quick-to-See-Smith, who Greenan represents, has seen her prices rise steadily, he says. A decade ago, large paintings were priced between $80,000 and $200,000. Now they range from $350,000 to more than $1m. The best works by Scholder and Morrison are also believed to sell privately for close to $1m and over $2m respectively, according to other experts. ‘Ironically, now I have people asking me if this is a bubble,’ Greenan says. ‘Well, you can have bubbles around anything, but the artists that are important will stay.’

Irene Snarby is an external curator on ‘Indigenous Histories’, specialising in the art of the Sami people. She says that their work was often dismissed as craft and while that has changed, artists still face many challenges. ‘In Norway, those that speak Norwegian can go to Oslo – but many don’t want to: they are deeply connected to their communities.’ Even fewer speak English, so reaching international curators is difficult. She adds: ‘Most live in remote areas and it is very expensive to send work unless it is film or photography.’

Horse and Rider (1977), Fritz Scholder. Courtesy Phillips

Some critics are tiring of the curatorial focus on identity politics. The Economist’s culture editor wrote of Venice that ‘you get the sense that the reason certain paintings are grouped together seems to be that the artists identify as indigenous or queer, rather than the work sharing any visual characteristics’. Having spoken to art advisers and a museum director, she added ‘the secret of this Biennale is that a lot of people found it unsatisfying’.

Others doubt the power of biennials to affect the broader market. As long ago as 2017, one of New York’s leading art advisers, Allan Schwartzman, wrote that ‘over time, with a few notable exceptions these sweeping Herculean shows have started to lose their prescience, their clarity and deep insight’.

Yet this Venice Biennale is filled with a rarely seen quantity of exciting and unfamiliar work, from the textiles of Argentinian/Wichi artist Claudia Alarcón to the jungle paintings of Peruvian/Aimeni artist Santiago Yahuarcani. It is a worthy successor to Cecilia Alemani’s 2022 edition, which foregrounded the work of women. That exhibition had an almost immediate effect on the market for female Surrealists, especially the work of the lesser known.

Of course, what is perhaps most appealing about Indigenous artists is the fact that the themes many embrace – the need to protect the environment, the sacred nature of land and animals, the importance of history, tradition and community – is antithetical to Western individualistic, industrial, consumer culture. A reckoning is sweeping parts of the art world. But it may not be a message that all of it wants to hear.

From the June 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Treister’s tarot offers humanity a new toolbox