The California-based artist talks to Gabrielle Schwarz about a new set of paintings on show at Pilar Corrias, which were made in response to the pandemic and which, like much of her work, address questions of race, gender and representation.

You have described your paintings as expressions of what it feels like to exist in a body that has multiple identities, or what you call ‘excesses of identity’. Are they self-portraits?

I really believe that I have to bring my own perspective and experience to the work. Much of what drives the work is the sense of my own identity as one that is often difficult to read. I find [this] especially with my race, as somebody who has a Black father and a white mother – who looks white, especially to white people – and then somewhat with my sexuality. I’m in a same-sex marriage, but I frequently have to go through a process of ‘coming out’. I think we all have this desire to be seen by other people the way that we see ourselves. So a lot of the work – you could say it’s self-portraiture – comes from wanting to find a visual representation for my own experience, which is not something that can just be summed up by the way that I look. It’s not about representing what it is look at a Black body or a multiracial body, but what it is to experience the world within that body.

It’s also in thinking about [such] ideas, and talking about them with other people, that I’ve found what seem to be shared experiences. You don’t have to be multiracial or queer to have times when an identity ascribed to you doesn’t quite match with how you experience yourself. I think we try to fit into certain categories, but inevitably we experience moments of contradiction. I think a lot about how different we are in different situations and encounters. By being really specific to my own personal experience, I’ve found that other people have come to me and said, ‘Oh, that is how I experience living in my body.’ I find there’s a weird paradox with making art, in which the more specific you are with your own experience the more it actually opens up the work.

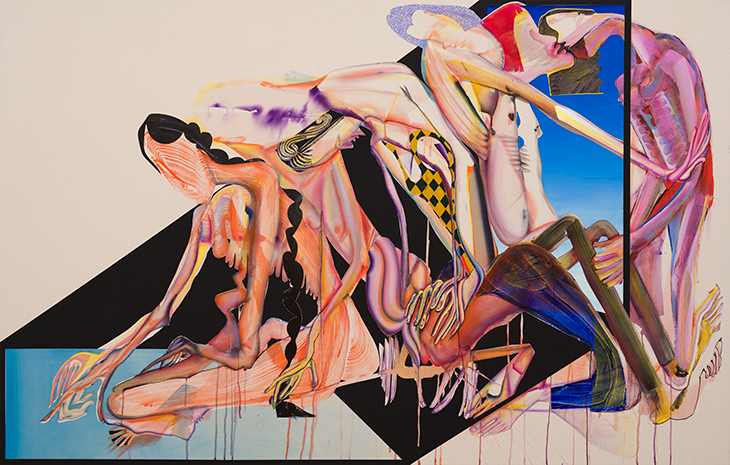

Lay Yer Burden Down (2020), Christina Quarles. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio; courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

Earlier this year your work was included in the Whitechapel Gallery’s survey of painting since 2000 [‘Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium’]. I’m interested in your choice of paint as a medium to explore identity and bodily experience.

I went to Yale for my MFA in 2014, and I graduated in 2016. I entered grad school seeing myself as somebody who made drawings – I started taking figure drawing [lessons] when I was 12 – and found that the medium was exciting for me in some ways but also limiting in others. You’re restricted to these small gestures, located in the wrist – rather than the broader gestures located more in the shoulder area [made possible by painting]. I switched big pieces of paper for large pieces of canvas, and essentially made a drawing on the canvas rather than on paper, with paint added to it. A lot of the compositional elements were the same in that there were large areas of exposed canvas – similar to how there would be large areas of exposed paper. I was interested to discover that people were fixated on the fact that I left areas of raw canvas exposed; I had made similar compositions with exposed paper and nobody commented. I understood that we view materials in certain ways and that they carry a history.

I realised that painting is an interesting allegory for living in a body. We don’t necessarily notice all the identities that are placed on us when we can move freely through a world that is designed to have those identities aligned with it. I don’t often think about being a US citizen, but I do think about my race and my gender and my sexuality, because those are things that deviate from positions of privilege. Just as in painting there are all these rules that if you follow them, they go unseen; but as soon as you start to move away from them, they’re the first things that you notice.

I’ll Take Tha Nite Shift (2020), Christina Quarles. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio; courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

You mentioned the physical experience of drawing versus painting. Can you say more about how you approach the canvas?

I start by making gestural abstract marks on the canvas, and they maybe incline towards certain body parts or compositions. I try to not complete the mark immediately but to leave it more fragmented, more open-ended. And then I spend a lot of time just looking at the work – trying to pull out unexpected images or connections. I’ll start to work out how the bodies are interacting and entwining and playing with the edge of the canvas, and I will flesh those out a bit more. And then I photograph the work and bring it into my computer, playing around with different possibilities. That’s when I start sketching, at this half-way point – that’s how I’m able to maintain the large areas of raw canvas that aren’t worked through – to figure out the composition. I start making more concrete decisions.

In fact, the computer allows for just as much experimentation and interaction between my intention and actuality. For example, sometimes I will decide that I want to do a pattern, like a filled-in area with grass. I’ll use the trackpad on the laptop, and fill the area in with a gesture, and I know that’s going to be filled in with solid paint in the ‘real’ world. But then I’ll get really attached to that scribbled gesture, and I’ll mimic the digital stroke back on the canvas.

They’ll Cut Us Down Again (2020), Christina Quarles. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio

Our experiences in the digital realm are something you deal with in your exhibition at Pilar Corrias. What drew you to this subject?

It would be impossible for me to make work right now that doesn’t reflect on how different our experiences and interactions are [due to the pandemic]. So much of my work is about moments of intimacy, and understanding people in all their contradictions. Now Zoom has ruined that, because we’re [all] these very flat faces. It’s resulted in this ongoing disembodied state – everything feels like we’re floating in space, rather than being anchored to more concrete experiences or moments of intimacy. Suddenly being very still and being at home, but then also having this strange, infinite digital reality, has created an interesting experience with multiplicity from what I’ve explored in my past work. But whether the work was made in the pandemic or not, the prevailing idea I’m exploring is what it means to inhabit your own body.

Tomorrow Comes Today (Come What May/Cum, Whatever, Maybe) (2020), Christina Quarles. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio; courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

How do you go about channelling all these experiences into your paintings?

In a few of the paintings, I’ve used a blue-sky gradient – for example, Tomorrow Comes Today (Come What May/Cum, Whatever, Maybe). The blue gradient is something that I’ve been using in my work for a few years now. It can represent a natural moment if it’s the sky, or it can be this very artificial moment with a desktop computer screen. I’m always looking for the planes and the patterns [in my paintings] to exist in this sort of visual punning space, to further add to the idea of figures existing in a state of multiplicity. And, here, I’m sure it is influenced by this ongoing interaction between digital space and the physical world.

The work is not meant to be narrative. It’s meant to have moments that can suggest a narrative instance – like the moment of interaction that’s the coming together of two faces, or the little face that’s looking away, or the gesture of coming through a window or being pushed away. I often see the work as multiple figures, but just as often I’ll see it as being a single figure, or maybe two figures moving through time and space. But it’s this sort of moment of isolation with projected memories behind it; this moving back and forth between the two.

Sweet Chariot (2020), Christina Quarles. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio; courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

Ambiguity plays a very important role in your work…

Yes. When I was an undergraduate I decided to take a break from making art and so turned to writing. I was interested in unpacking my racial identity, finding a way to describe my experience as something other than being ‘mixed’, because I felt like that word implied a unified identity. My experience was more that I had Black experiences and white experiences, and experiences that were undercut by having both of those experiences simultaneously. I was ultimately looking for a way to understand being multiply situated and existing with simultaneous contradiction. I found that it was really difficult for me to work through these ideas with language because it exists in such a linear way. Visual language is not exempt from linearity, but there’s a way of talking about simultaneity in visual terms that can be more organic than in written form.

There’s a moment in the 1984 movie Amadeus when the Mozart character is talking about the Marriage of Figaro, and he says something like, if you have an argument in a play and people are talking over each other, you can’t hear anything. But if you put it to music, it’s suddenly in harmony, and it’s beautiful to have many people talking at once in song. I think about that a lot with painting. You can actually have an image that’s legible, beautiful, interesting and engaging even when it’s all happening at once.

Museums and galleries in the UK are closed from 5 November due to Covid-19. For more information on ‘Christina Quarles: I Won’t Fear Tumbling or Falling/If We’ll be Joined in Another World’ (scheduled to run until 21 November) visit the Pilar Corrias website.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why it’s time to stop rediscovering Eileen Gray