For the latest Met Roof Garden Commission, Huma Bhabha has installed two large-scale bronze sculptures in the ‘open theatre’ overlooking Central Park. If they appear alien, they come in peace, she tells Apollo.

How have you approached the Roof Garden Commission at the Met?

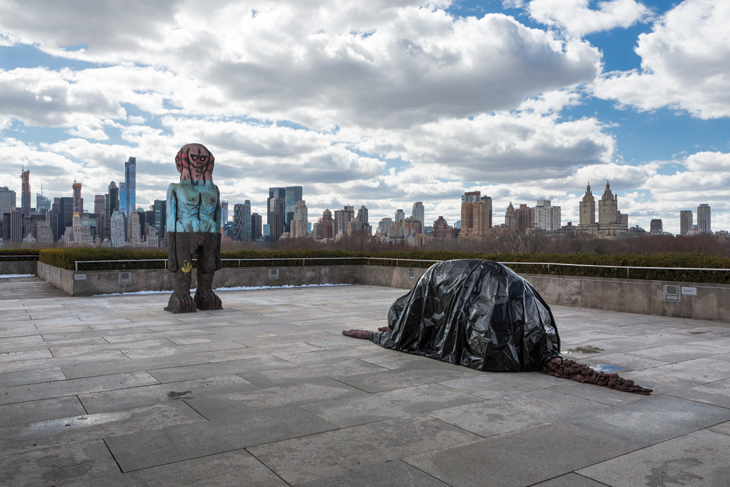

In the past I’ve thought a lot about the theatrical element that’s needed to make an installation successful. As the roof at the Met is a space that feels very much like an open theatre – it’s in the middle of Central Park – I decided to treat it like a stage. The sculptures would be actors on a stage. To my mind, it also felt like a landing pad, where the sculptures could have arrived as visitors; the curator Shanay Jhaveri and I talked about the idea of a sort of first-contact narrative. I wanted to make bronze sculptures in a large-scale format – I’ve worked with bronze in the past, and since these works were going to be outside, for me it was the perfect material to use.

The title of your installation – ‘We Come in Peace’– sounds like both a political statement and a joke about sci-fi films. How do these two things work together in your work?

There are a lot of different ways of approaching the political climate, and

I think a lot about current events – and not just from the last year or so. The title is supposed to make the viewer feel comfortable, in terms of allowing them to come up with their own interpretations of the sculptures. There are two sculptures on the roof, and they are in dialogue with each other – they could be comrades, or one being summoned by the other. I want to create the idea of different sorts of theatrical scenarios. Yes, the title carries a lot of political connotations, which is fine with me: I am in a sense bearing witness to the times.

Installation view of ‘The Roof Garden Commission: Huma Bhabha, We Come in Peace’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: Hyla Skopitz; © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

And what about the sci-fi aspect?

There’s definitely an element of humour in my work, and I’ve been interested in horror and science fiction for a while. The title does relate to the idea that, for me, it feels like the sculptures have landed on the roof. When I first experienced movies like Alien and Terminator, and early Cronenberg, it opened a door for me as to how I wanted to take my figurative sculpture. I’m interested in why those movies exist, and why science fiction and horror have become such successful genres – and in particular how they relate to actual events.

Sculptures might be said to have an alien quality too, at least metaphorically, in how their forms or traditional functions (as idols, or totems, or monuments, for instance) can disrupt our usual modes of perceiving the world around us…

Definitely. Making sculpture is like that too – it allows you to take yourself out of the normal mode of approaching the world, and have the freedom to think on different scales… to create not just monumental forms, but actual monuments.

Your work has previously been compared to a number of figurative sculptural traditions. How far have you drawn inspiration from the collections at the Met itself?

Not from any specific piece or period, but the variety and depth of the collection reflects my own interest in historical sculpture from different times and places. I’ve been working with certain materials in a particular way for a few years, and the two sculptures draw on that: one of them is a reclining figure, one an erect totem. What has changed is that the scale is much larger. I always thought that would enhance the presence of some of the pieces I was working on. I made the models to scale before they were cast in bronze – it was very important for me to see them actual size, rather than making them smaller and then having them enlarged.

Your bronzes have very rough surfaces, and have been described as looking like meticulously fabricated ruins. How important is that look of antiquity to you?

I never try to make anything look weathered or like an antiquity. When I first started working with clay, I hadn’t been trained to work with it, so it was just the way that I approached the material. I think it’s my natural inclination to treat each material in its own way, whether that’s drawing on paper or carving or scratching on a sculpture. It’s not so much that I want to get a certain look, it’s just the way that I feel I want to treat the material. My work has a strong expressionistic quality, which for me is about working in a spontaneous, natural way.

‘The Roof Garden Commission: Huma Bhabha, We Come in Peace’ is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until 28 October.

From the May 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)