Joe Brainard was glad he wasn’t Andy Warhol. In a career that overlapped with Warhol’s, Brainard designed theatre sets and book covers; he drew cartoons, painted paintings and assembled collages. He is, however, probably best remembered for his memoir, I Remember (1975), a book of fiercely observed reminiscences that all begin, ‘I remember…’ and which Paul Auster called ‘A little masterwork’. And yet, despite Brainard’s association with Pop art, as well as with the New York School poets and writers, he has remained largely uncategorised and under-appreciated; such, perhaps, is the curse of the pluralist. In an interview with Little Caesar magazine in 1980 he said, ‘People want to buy a Warhol or a person instead of a work. My work’s never become “a Brainard”.’

It is perhaps appropriate then, that on the 50th anniversary of the publication of all three parts of I Remember, Craig Starr Gallery has mounted an exhibition of Brainard’s Nancy series, works that feature a cartoon strip character who is recognisably not a Brainard creation. Nancy, a frizzy-haired child in a scholastic uniform of collared shirt, sleeveless black pullover and red skirt, is the creation of newspaper cartoonist Ernie Bushmiller, who began drawing her in 1933. Brainard co-opted Nancy in 1963 and would go on to make more than 100 drawings.

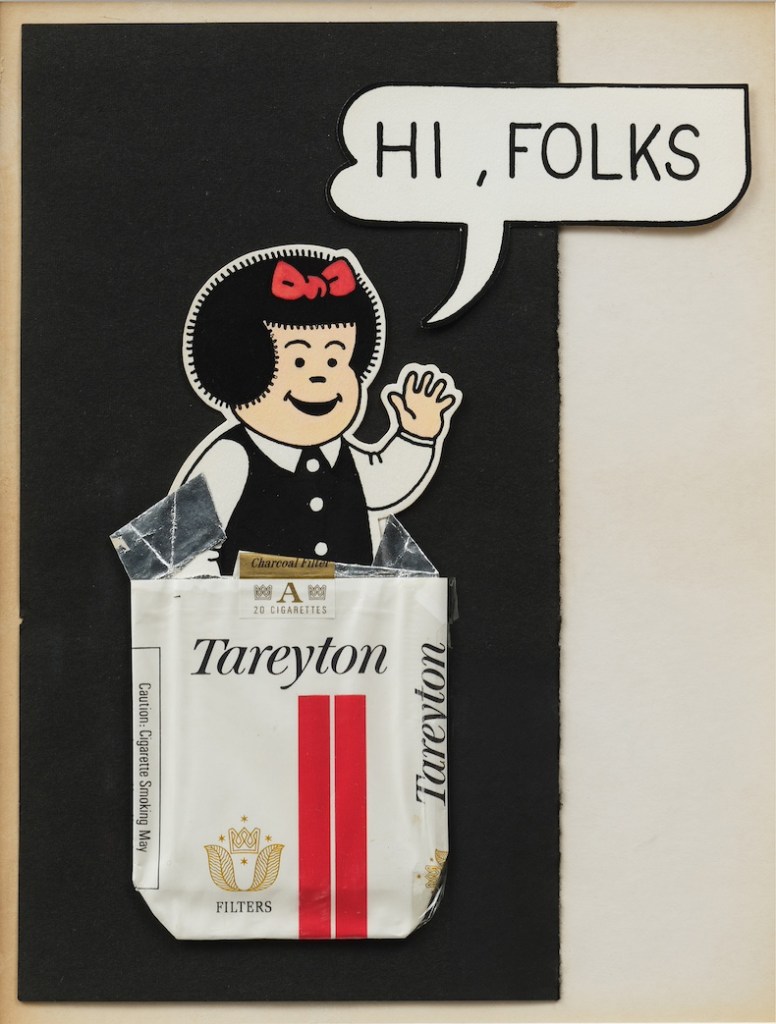

Untitled (“Hi, Folks”) (c. 1965–68), Joe Brainard. Photo: Thomas Barratt Photography; courtesy Craig Starr Gallery, New York

That Nancy is simple – both in her features and by dint of the fact that she is a child – allows Brainard to use her as a kind of pictorial Passepartout. Hung across three rooms in Starr’s gallery in New York’s Upper East Side are 17 Nancy works from 1965–74, many on loan from Colby College Museum of Art in Maine. In Untitled (“Hi, Folks”), from around 1965–8, Nancy emerges waving from a flattened packet of cigarettes, Brainard’s constant shirt-pocket companion (he smoked up to four packs a day). Fear and Some Studies for Fear (both 1972) feature Nancy in choreographed panic: running, jumping, sweating and gesticulating. In both works, however, it is Nancy’s open mouth that stands out. In Studies, its rendered black void is peppered across the surface of the work like gunshot; and in Fear itself, her mouth becomes a sharply drawn black hole emitting a silent scream.

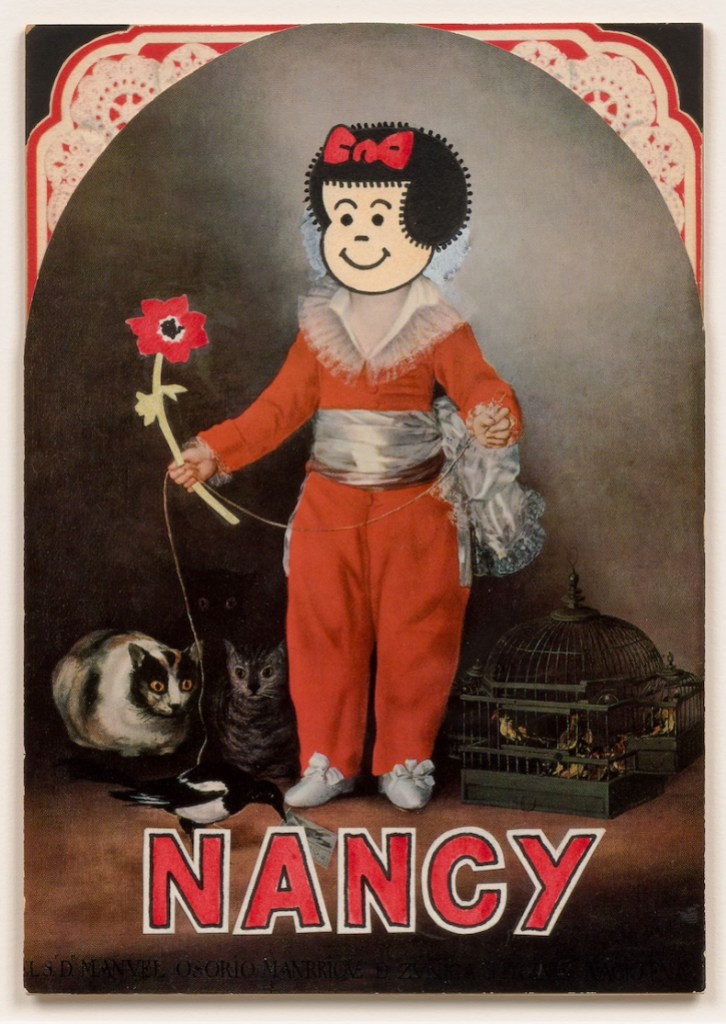

While Nancy, a character all her own who had broken free from another comic strip, often serves as a way for Brainard to explore his anxieties – both Fear works seems to epitomise US Cold War paranoia, even calling to mind the propaganda cartoon Duck and Cover – she can also be a way to engage with the art historical canon. Untitled (Nancy as a Goya) (1968) shows Nancy’s head transposed onto Goya’s Red Boy (1787–88). At first, it is almost uncanny how well Nancy’s face maps on to that of Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zúñiga, the young Spanish aristocrat in the painting. The hair, gormless facial expression and red clothing all come together so that for a moment one seems to be looking at an updated version of Goya’s painting rather than a bowdlerised Old Master. In Brainard’s version the six watchful eyes of the boy’s pet cats still glare at the magpie he leads by a string, but Brainard has also inserted a poppy into the child’s hand as well a lacework arch above him and the word NANCY below. De Zúñiga died a few years after Goya painted him; he was eight years old, just like Nancy. In Brainard’s iteration, the two merge in a representation of eternal childhood.

Untitled (Nancy as a Goya) (1968), Joe Brainard. Photo: Pierre Le Hors; courtesy Craig Starr Gallery, New York

What strikes me most about these Brainard works is the particularly American nostalgia that Nancy evokes. In her indefinite infancy, Nancy hearkens back a yesteryear when only girls wore dresses and boys had scraped knees and Coca-Cola came in glass bottles. But nostalgia is two-dimensional to memory’s three and Nancy stands in stark contrast to the specificity of I Remember, offering up what – to me, at this particular moment – feels like a challenge to the giddiness of the MAGA movement: to be ignorant of history is to remain forever a child.

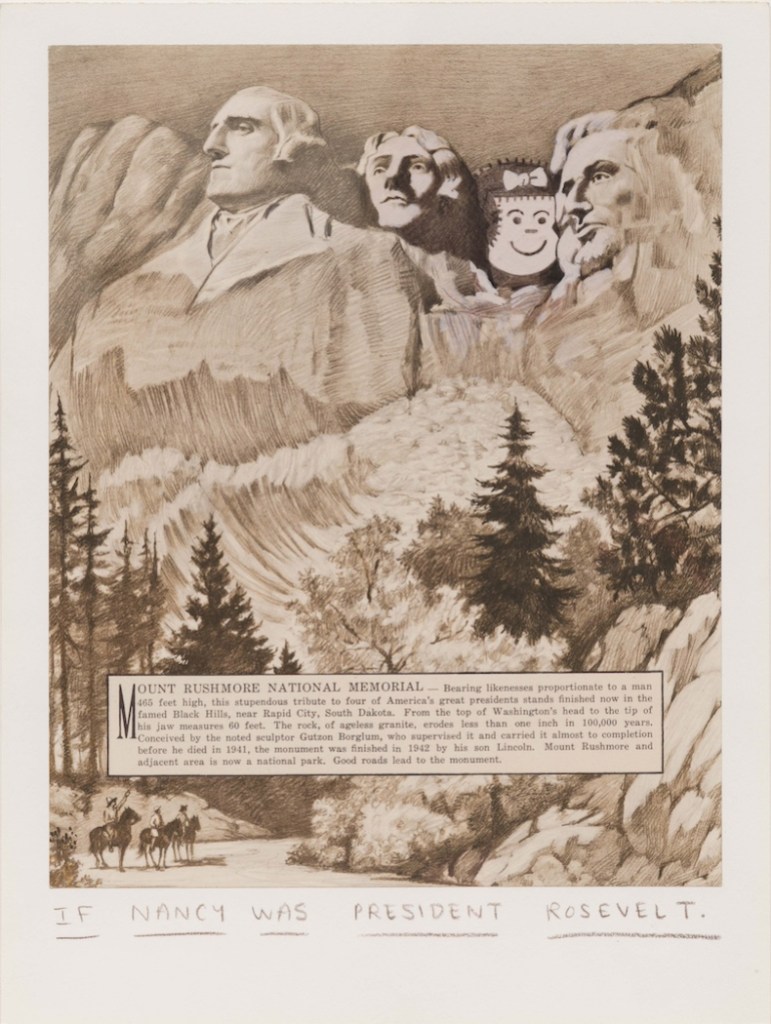

Before I left this excellent show, I returned to look again at a work in the middle room of the exhibition. If Nancy Was President Roosevelt (1972) shows Nancy’s impudent face inserted into Roosevelt’s place on Mount Rushmore, tucked between Jefferson and Lincoln. In late January, a Florida congresswoman introduced a bill proposing to add Donald Trump’s face to the national monument. Looking at Brainard’s piece, I was reminded of how quickly a joke can become more serious. In her innocence, Brainard’s Nancy is a warning to resist the easy appeal of nostalgia.

If Nancy Was President Roosevelt (1972), Joe Brainard. Photo: Colby College Museum of Art; courtesy Craig Starr Gallery, New York

‘Joe Brainard: Love Nancy’ is at Craig Starr Gallery, New York, until 28 June.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze