This review of John Craxton: A Life of Gifts by Ian Collins was published in the May 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

For an artist, John Craxton could not have wished for a more congenial upbringing. He was born in 1922, the fourth of six siblings, to Harold Craxton, a professor at the Royal Academy of Music, and his wife Essie. Both were well connected in bohemian circles. The family home was a ramshackle set-up in St John’s Wood stuffed with animals, bicycles and antiques. At the age of 13 Craxton was the star of a school show in London; at 19 his work appeared in Horizon. The magazine’s art editor, the influential patron Peter Watson, bought Craxton’s Poet in Landscape (1941), a picture Ian Collins calls ‘the poster image for British Neo-Romantic art’. Samuel Palmer and William Blake were early and enduring influences. Craxton later dismissed the Neo-Romantic label (‘You are either a Romantic in spirit or you are not’), but his images of moon-faced dreamers repining in landscapes of rocks and swollen vegetable matter undeniably caught the mood of the moment. In 1944, an entrance-hall show at the Leicester Galleries virtually sold out; he was still only 21.

Landscape with Poet and Birdcatcher (1942), John Craxton. Private collection

Constant chest and lung complaints made him detest damp England. He began to long for Greece, a country for which he felt a deep affinity without actually having been there. Graham Sutherland, an early admirer and mentor, advised him to ‘paraphrase reality’ in his work. Craxton needed little encouragement: trips to the Scilly Isles and Pembrokeshire were enough to inspire paintings with titles like Greek Fisherman. He finally made it to Greece in 1946, quickly establishing friendships that would last the rest of his life – with author (and fellow show-off) Patrick Leigh Fermor, his girlfriend Joan, and the Greek artist Nico Ghika. Craxton went on to draw the covers for almost all of Leigh Fermor’s books. Collins’s subtitle echoes Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts (1977), while also hinting at the generosity of friends that Craxton, serially out of pocket, relied on throughout his life – and, to be fair, showed to others when he had the means.

John Craxton’s cover for Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts (1977)

On the island of Poros, where he went on Leigh Fermor’s recommendation, he found quarters in the harbourside house of a respected local family and learned a demotic form of Greek punctuated by curses learned from sailors’ bars. He liked to move between high and low society, something he shared with his best friend at the time, Lucian Freud, who soon joined him on Poros. United in their nonconformism, they had shared a studio back in London; in Greece they prowled about, drawing the agaves and each other, scrounging for meals and art supplies. This friendship soured as time went on. Freud met Francis Bacon. ‘Lucian began to drop me when he found a better painter,’ said Craxton. Later in life, Freud freely slagged off his erstwhile friend; to his biographer, William Feaver, he gave the impression of Craxton as a narcissistic gadfly who pilfered statuettes from Greek roadside shrines. But then, Freud had a staggering capacity for spitefulness. Collins’s loyalties lie clearly with his subject: the shame, he says, is that Craxton, an essentially affable spirit, ‘returned the bitter sentiment’.

On Poros, the grand Villa Serenity inspired his first Greek landscape, Hotel by the Sea (1946). With its ‘faceted and fractured planes of light and colour’, it carried the influence of Picasso but also of the blazing Greek sun. Ever brighter colours began to fill his paintings; polychromatic outlines were added to objects and figures to convey the radiance of southern Mediterranean light. For the rest of his life, Craxton spent as much time as possible in Greece, in 1962 taking a lease on a Venetian house in the harbour town of Chania. A terrace looked on to the Cretan Sea and the White Mountains, where Craxton, with a moustache like a Cretan shepherd’s, liked to take his motorbike in search of local hospitality and medieval churches, the crumbling frescoes of which he might set about spontaneously uncovering and cleaning himself. In his own work, cubism and oil paint gradually ceded to Byzantine linearity and tempera. A nearby NATO base brought regular waves of ‘gorgeously uniformed soldiers’. Collins compares Craxton’s carefree escapades in tavernas to the misery of other gay British artists of the time. Fundamentally he was a hedonist for whom politics could only ever get in the way. His single political painting, about the war in the Balkans, was childish. In a telling anecdote, he said once that John Berger only began to like his work when, as a joke, he told him that he painted people shoeless as a political protest.

Two Men in Taverna (1953), John Craxton. Private collection

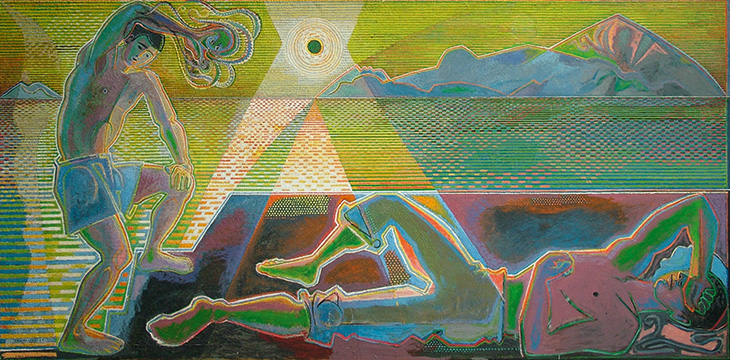

Collins says Craxton procrastinated because he prioritised life over art. Was he also, perhaps, afraid of failure after being feted so early on in life? His star certainly waned; in post-war London, figurative painting was hardly in vogue (as even Freud found out). A retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1967 ‘drew at best a tepid response’. Featured in the show was Two Figures and Setting Sun, a large painting with which Craxton had been struggling for 15 years. It shows Craxton achieving something like the beatific visions of his beloved Blake and Palmer, but in his own idiom – the electric colours, the geometric patterning, the sensual figures. I wish he’d done more like it. He remained dissatisfied with the work and consigned it to a back room, where it was discovered after his death.

Two Figures and Setting Sun (1952–67), John Craxton. John Craxton Estate

No one knows more about Craxton than Ian Collins, who befriended him in the years leading up to his death in 2009 and persuaded the artist to grant him taped interviews. Here he presents a portrait of a genial rogue whose wit and joie de vivre won him numerous friends and lovers, for all that he constantly tapped them for lunch money. Landscapes and meals are described in appropriately sensuous detail, and Collins is a good reader of the paintings, though I think he overstates the case when he writes that ‘First, last and always, John Craxton’s concern was with the individual.’ Craxton’s figures and faces are mostly interchangeable. His talents lay in the joy he generated through composition and colour. That sense of joy was integral to the life he led, and Collins has conveyed it in a rich and sympathetic book.

John Craxton: A Life of Gifts by Ian Collins is published by Yale University Press.

From the May 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)