From the May 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

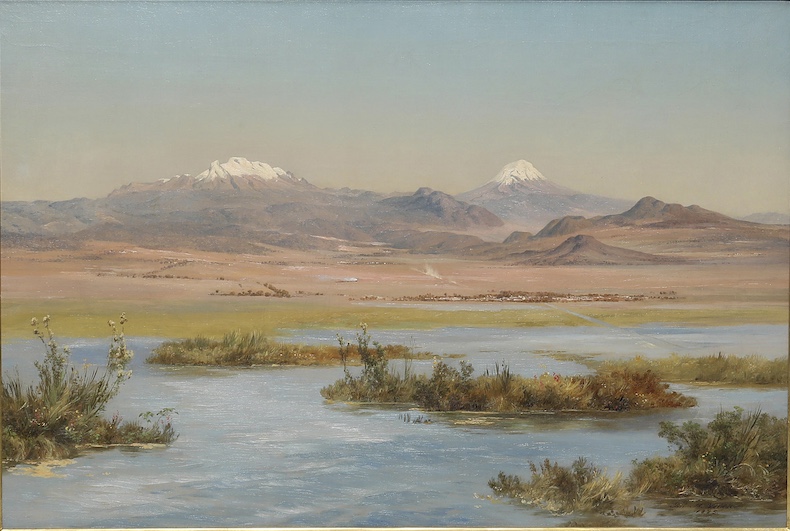

José María Velasco is now recognised as Mexico’s pre-eminent 19th-century painter and an important influence on later, more familiar artists, including his student Diego Rivera. This exhibition is the first solo show of his works in the UK; it is also the first time a Latin American artist has been given a dedicated exhibition at the National Gallery. However, what visitors are introduced to first is not Velasco’s range or variety. Instead, the opening three paintings take up the same subject. Lake Chalco (1885), The Valley of Mexico from the Molino del Rey (1895), and the larger-scale The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel (1875) look out across the Valley of Mexico toward the volcanoes Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl topped with snow. Skies are variously clouded or unclouded; in the latter painting, a portentous rainstorm blows in from the southeast. In the foreground of each painting we see, respectively, a lake, a scattering of buildings, two people and their dogs, all rendered in luminous detail. In the middle distance, across the 30 years that separate the painting of these three pictures, the beginnings of Mexico City take shape as the waters of the surrounding lakes recede.

Lake Chalco (1885), José María Velasco. Photo: Andrea Rývová; © National Gallery of Prague

The effect of this opening is complex. On the one hand, the viewer experiences a feeling of déjà vu as they move from one view of the valley to another. Such repetitions may repel attention but they also have the potential to encourage it. As visitors walk through the show, they learn that Velasco’s paintings, in their frequent returns to favourite themes, often require looking twice: once to see what remains from earlier views of the same landscape and again for the processes of disappearance and renewal that emerge as his primary subject.

Such processes were to some extent a matter of scientific interest for Velasco. Like many 19th-century artists, he saw his project partly as documentary, and he published in scientific journals and illustrated scholarly works such as the Flora del Valle de México (1869–70). Velasco’s commitment to accuracy can be seen everywhere in this exhibition – in the studies of birds’ wings completed in preparation for painting the harpy eagle of another View of the Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel, painted in 1877; in paintings such as the unfinished Mafaffa Leaves (n.d.), reminiscent of a naturalist’s catalogue of the period. The leaves in question have been rendered with absolute precision, while the forest in which they sit slowly encroaches from the left. The Forest of Pacho (1875), with its flattened pictorial plane, could be read as another cataloguing exercise. There, however, evanescent light filtering through the upper canopy on to the foliage in the foreground alerts the viewer that we have left the timelessness and placelessness of the naturalist study.

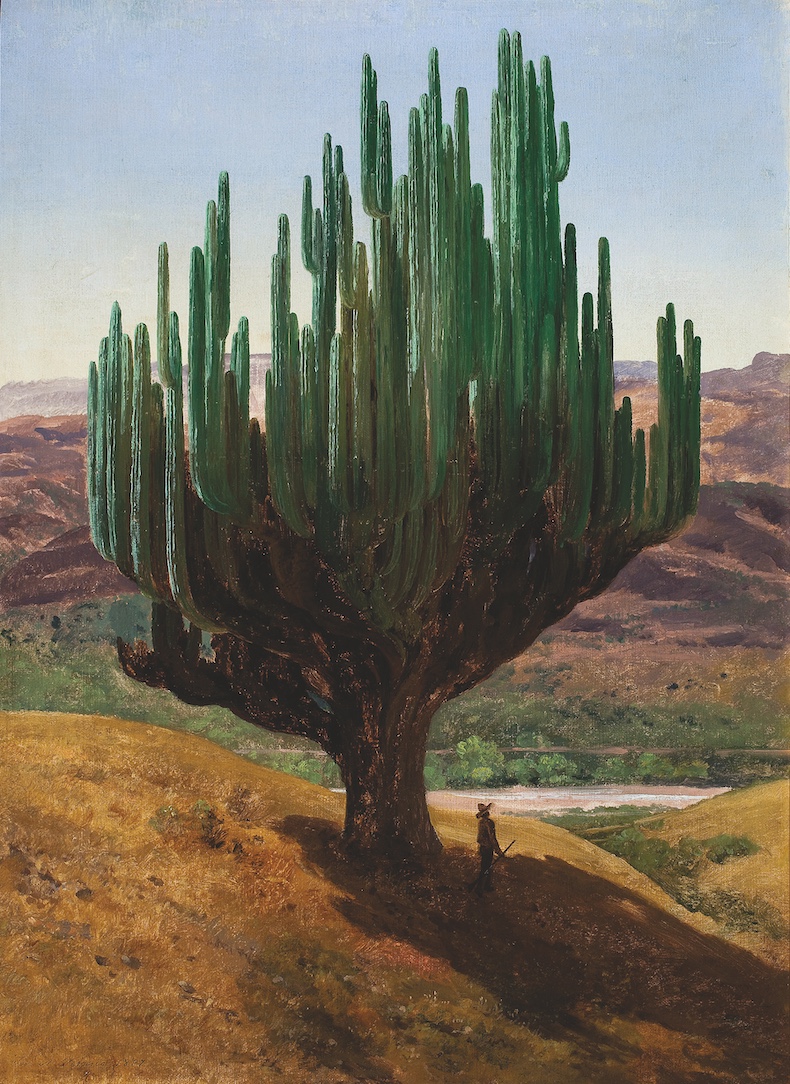

Cardón, State of Oaxaca (1887), José María Velasco. Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL, Mexico City. Photo: © Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura, 2024

Such subtle calibration of situation – the tweaking of documentary fixity into temporal, even historical, contingency – is a common trope of Velasco’s work. Again and again, sublime vistas such as those of The Textile Mill of La Carolina, Puebla (1887) or Temascalcingo (1909) are interrupted by traces of human activity – a factory wall, the perfectly straight lines of aqueducts or city streets as they are laid out, smoke from a passing train that is itself too small to see. In part, these encroachments of rectilinearity and smoke repudiate the ahistoricism, or at least the non-specificity, of landscape paintings by European predecessors whose style Velasco’s teacher Eugenio Landesio imitated, such as Claude Lorrain or Nicolas Poussin.

But if Velasco’s paintings are extraordinary in their registering of modernity’s encroachment on the natural world, more interesting still is his desire to measure out the scale of human activity. The smokes of Velasco’s factories and trains are often juxtaposed with the vastness of Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl – one of his last completed works, the impressionistic Eruption (1910), imagines an apocalyptic return of volcanic activity on the back of a postcard. Such experiments with scale and proportion are everywhere in Velasco’s work. Look at the giant cactus of Cardón, State of Oaxaca (1887) or the lovingly rendered glacial erratics of Rocks on the Hill of Atzacoalco (1874), both of which hinge on a juxtaposition of immense natural objects with diminutive human figures.

Eruption (1910), José María Velasco. Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL, Mexico City. Photo: © Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura, 2024

During Velasco’s lifetime, Mexico came recognisably into being as a state, its modern borders largely set by the military opportunism of the United States in the war of 1846–48. Constantly changing in shape and historical trajectory in the second half of the 19th century, Mexico existed in a state of continual flux. Velasco’s obsessive testing of contingency against permanence represented a critical way of probing both personal and national identity during this period of transformation. At times, he did this with great confidence, painting a real-life version of the eagle and the cactus of Mexico’s coat of arms into his monumental masterpiece View of the Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel (1877).

At other times, for all of the temporal space it may appear to occupy, nature seems less certain as a source of stability. The final work of this exhibition, an unfinished Study of Clouds (1912) painted on a postcard, leaves the planned landscape unpainted, though the Valley of Mexico is again set out in outline. Here, one feels, the natural world seems very small and very impermanent. Nevertheless, Velasco keeps looking.

The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel (1877), José María Velasco. Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL, Mexico City. Photo: © Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura, 2024

‘José María Velasco: A View of Mexico’ is at the National Gallery, London, until 17 August.

From the May 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze