At one point in Frank Wedekind’s play The Marquis of Keith, written in 1901 and set in 1899, the eponymous swindler describes Munich as ‘an Arcadia and at the same time a Babylon’. His words sum up the contradictory nature of Jugendstil, the art movement that bloomed in the city and in Weimar and Darmstadt at the turn of the 20th century. Jugendstil was a variant of art nouveau, which was sweeping Europe and North America at the time; it took root in Munich in 1893 and lasted around 15 years, ushered in by a group of artists who sought to escape the constraints imposed by fusty professors in the state academies.

It is somewhat ironic, then, that the Stadtmuseum in Munich made collecting the artefacts of Jugendstil central to its mission after the Second World War, and is now home to the world’s richest assembly of objects from the period. The exhibition ‘Jugendstil. Made in Munich’ – held at the city’s Kunsthalle while a seven-year renovation of the Stadtmuseum continues – encompasses an extraordinary range of media: furniture, dresses, magazines, ceramics, appliances, interior designs and facades, all reflecting their makers’ desire to reshape their lived experience.

An armchair upholstered in leather (1904), designed by Bruno Paul and made by the United Workshops for Art in Craft, Munich. Stadtmuseum, Munich; © Bruno Paul, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

The makers who created these objects were inspired by the notion of Gesamtkunstwerk, or ‘total work of art’. This ideal was first propounded by Richard Wagner, so its currency in a state whose king had been Wagner’s great patron seems appropriate, but the Jugendstil artists were equally inspired by the English Arts and Crafts movement, a reaction to technological progress and mass production.

In the closing years of the 19th century, the city, and Germany more widely, underwent a major industrial expansion, with Munich’s population doubling between 1883 to 1901. Munich had long been a mecca for the arts, thanks to generous state patronage by the Wittelsbach monarchy, and among this latest influx of people was a sizeable contingent of creative artists and makers. Käthe Kollwitz, Gabriele Münter, Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky are among those who flocked to Munich from other parts of Europe, America and Asia, attracted by its liberating atmosphere, especially its innovative, privately run art and design schools. Women, banned from art schools elsewhere, were drawn to the Damen-Akademie (Women’s Art Academy), founded in the 1880s.

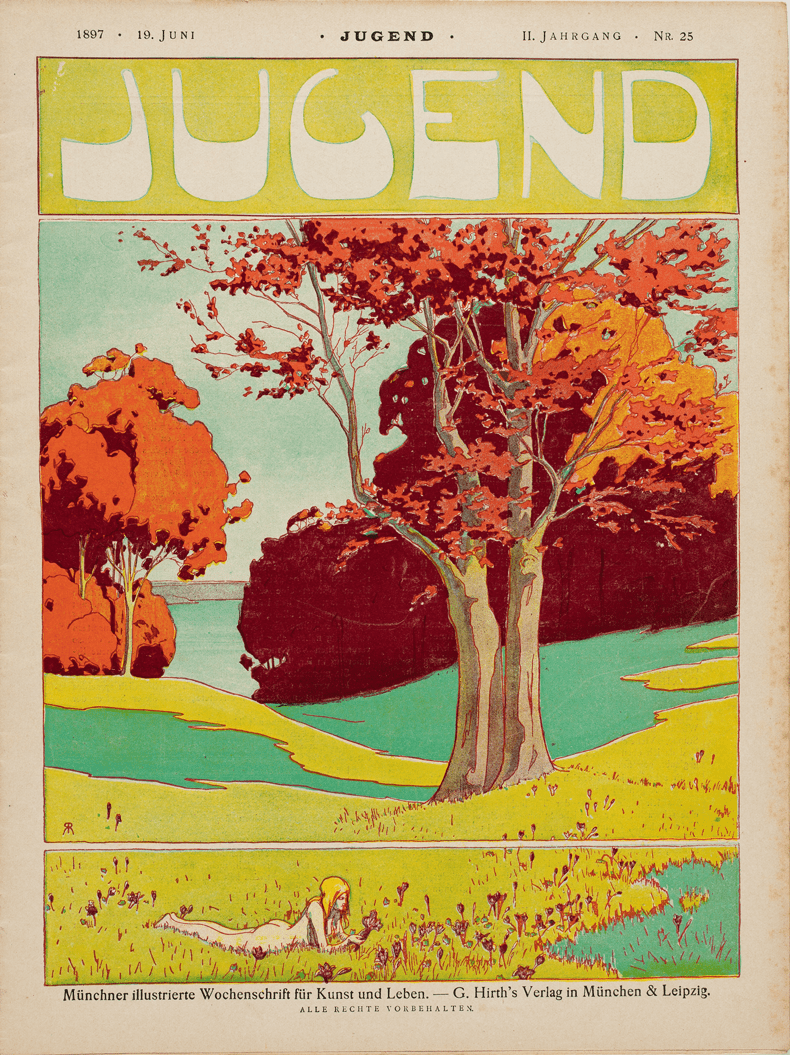

Cover of Jugend, an illustrated weekly Munich magazine. Stadtmuseum, Munich. © Richard Riemerschmid, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Almost every form of art, design and urbanism produced during the movement seems touched by a sense of urgency, a feverish quality. At the exhibition, this is perhaps best reflected by a selection of eye-catching weekly magazines that proved a major stimulus to Jugendstil: Muenchner Illustrierte Wochenschrift, Jugend, Simplicissimus. Their designers used colour lithography for the often sexually provocative covers and for the posters plastered on advertising columns, which often enraged conservative passers-by.

In 1898, the architect and designer August Endell announced: ‘We stand at the beginning of an entirely new kind of art, with shapes that do not have a meaning, that do not represent anything and remind us of nothing, that stir our soul as deeply as only music does.’ Given this scepticism about figuration, it makes sense that a work by Hermann Obrist, creator of some of the earliest abstract sculptures in Europe, takes pride of place at the Kunsthalle. He conceived a flower design that was stitched by the artisan Berthe Ruchet around 1895 – a semi-abstract wall hanging, with looping curves and shimmering needlework. Here, with the help of a digital animation, delicate tendrils spring to life, growing and spreading before viewers’ eyes.

Whiplash (Wall hanging with cyclamen, c. 1895), designed by Hermann Obrist and embroidered by Berthe Ruchet. Stadtmuseum, Munich

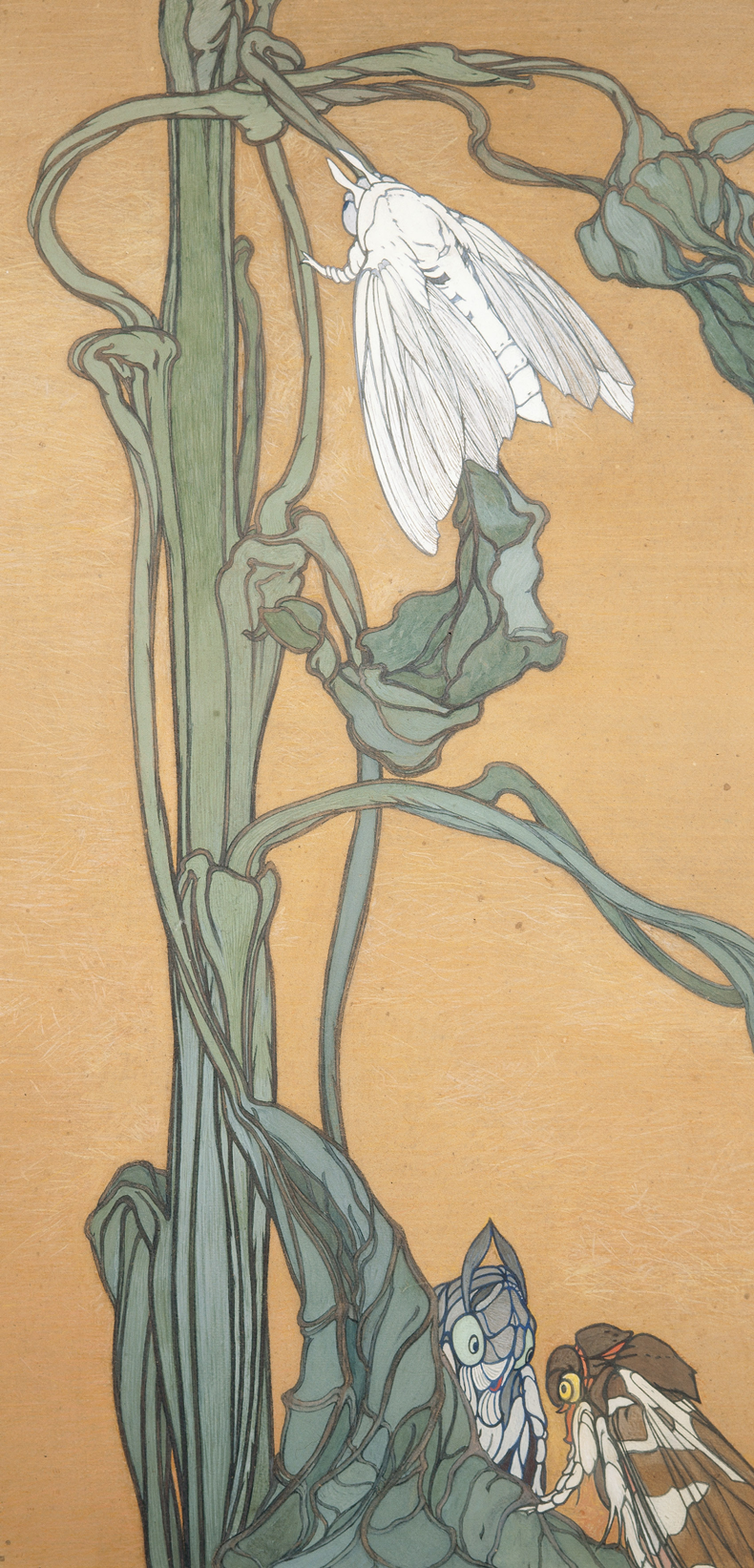

The desire to convey the energy of natural growth prevails everywhere. In Elisabeth Erber’s closely observed drawings, moths perch on elongated plants that droop and wind their way along scroll-like panels. Fluid movement prevails, from Bernhard Pankok’s carved wooden benches to assorted bedsteads and wardrobes. Perhaps most successful is Richard Riemerschmid’s lamp, which sprouts organically out of a brass base, its opalescent lampshade shaped like flower petals. The silversmith Gertraud von Schnellenbühel took these natural visual similes to an extreme with her brass and silver candelabra, completed in 1913. Its 24 branches seem a cross between a fruit-laden apple tree and a creature from outer space.

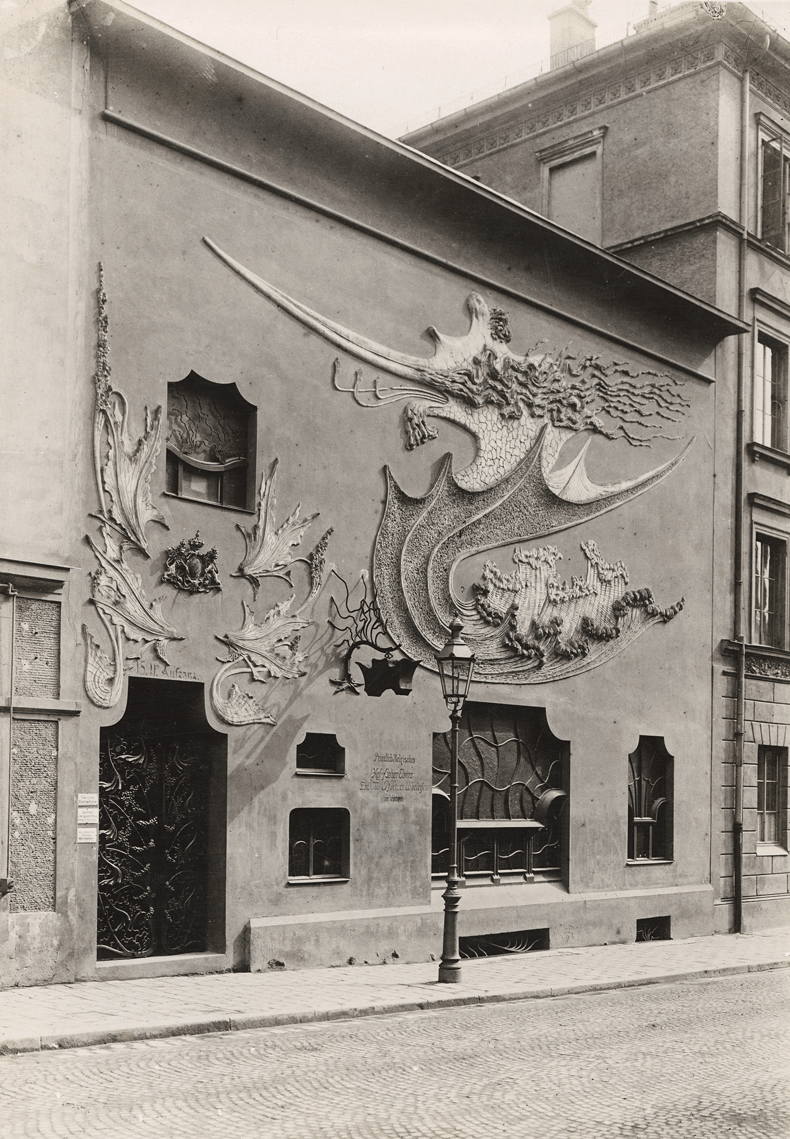

Though most of the Jugendstil architects were men, it was two queer women, the jurist and actress Anita Augspurg and the photographer Sophia Goudstikker, who commissioned Endell to design the most iconoclastic building of its day – the Hofatelier Elvira, a photography studio frequented by a number of aristocrats. The dramatic colours and shapes of Endell’s facade have been recreated here by designer Bodo Sperlein: a twisting purple sea-creature cavorts over a deep green backdrop, hovering over a Hokusai-like wave. A photo taken in 1900 by Philipp Kester gives a flavour of how striking the building, dubbed ‘octopus rococo’ by critics, would have looked to contemporaries. The shop front was torn down during the Nazi period and Obrist’s studio, also designed by Endell, was destroyed by bombing in 1944. Until now they were known only through black and white photographs, so the Kunsthalle’s reconstructions – which revive the designer’s daring and emotive use of colour – carry a special poignancy.

The exterior facade of Hofatelier Elvira in Munich, c. 1900. Photo: Philipp Kester; © Münchner Stadtmuseum, Kester Archive

Munich lost more than half its buildings in wartime bombing raids, but Jugendstil lives on in the city – in the Müller’sches Volksbad on the banks of the Isar river, a complex of public swimming baths conceived as a ‘hygiene cathedral’, and in the decorated facades of lovingly restored residential blocks. It is by walking around neighbourhoods such as Haidhausen, Au, Schwabing and Bogenhausen, with their attractive, irregular layouts, modestly scaled streets, human-scale buildings, and squares and garden areas, that the spirit of Jugendstil is most strongly felt – something no single exhibition, however ambitious and comprehensive, can capture.

Leaf Stalk with Three Moths (c. 1899), Elisabeth Erber. Stadtmuseum, Munich

‘Jugendstil. Made in Munich’ is at the Kunsthalle, Munich, until 23 March 2025.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)