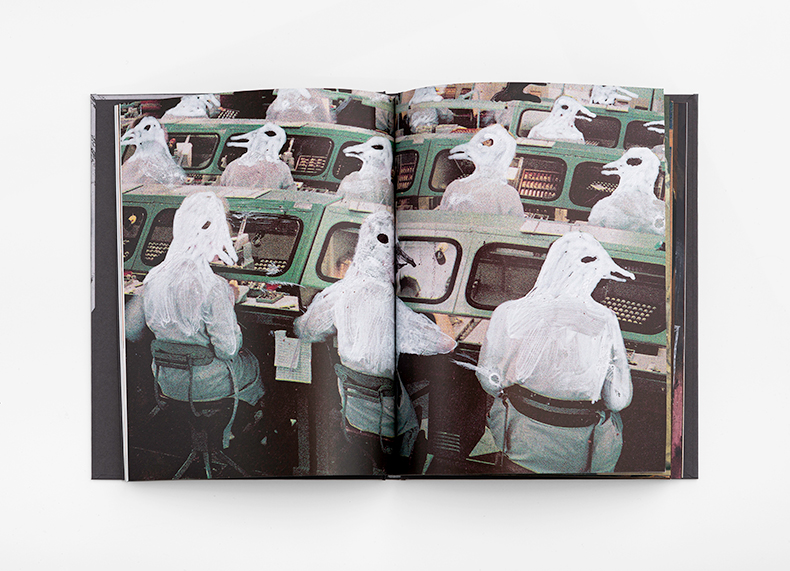

‘I think everyone has their own interpretation,’ says Julia Soboleva. ‘For me it’s very emotional because I can’t not make images. I just need it.’ She is talking about her monograph I have found the light in the darkness, which she published last year with Witty Books. Featuring no text, aside from the credits and a brief end quotation from Frank Herbert’s Dune, it’s an enigmatic and sinister affair. Strange creatures dominate, performing what look like weird experiments with dated technology or human bodies; there’s some sort of narrative at work, perhaps showing these creatures being born, travelling, landing, and infiltrating earth. Although this is just my reading. It’s not necessarily how Soboleva sees it, though she’s pleased Witty’s publisher Tommaso Parrillo and the book designer, Giulia Boccarossa, found this coherence in her images. For Soboleva this book was instinctive, as is her work in general.

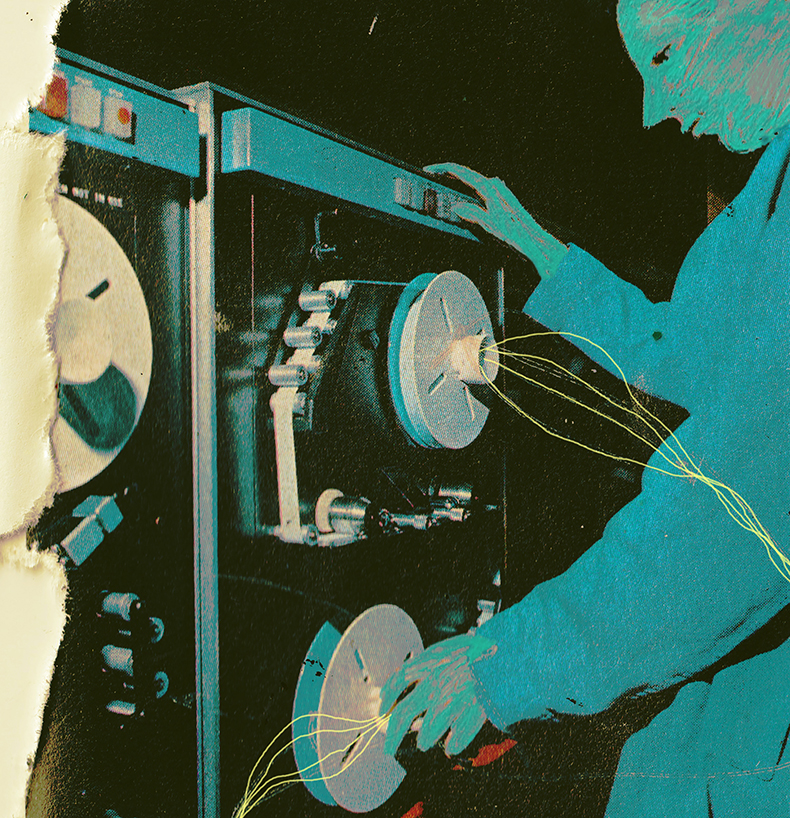

From I have found a light in the darkness by Julia Soboleva (Witty Books)

‘I’m constantly inspired by many, many things, both artistic and personal,’ she says. ‘Often I’m trying to process my emotions but there’s also music, the whole bunch. But it’s always intuitive. I just follow what feels right without explanation. I’m a single parent so I don’t have a lot of time – I don’t have time to plan or make sketches. I just thought, “OK I’ll make that my method.”

It sounds carefree but the intensity of her book suggests otherwise, as do the correspondences Parrillo and Boccarossa found in her images. It is partly down to the way Soboleva made them, by painting on top of found photographs; she adopted this approach about four years ago, and now spends most of her working time seeking out suitable shots in Manchester’s flea markets and charity shops. The photographs she finds influence how her images look, and with I found the light in the darkness she was mostly working with a encyclopaedia from the 1960s. Its articles on dated technology attracted her, she says, because they reminded her of Soviet factories.

From I have found a light in the darkness by Julia Soboleva (Witty Books)

Soboleva was born in Latvia in 1990 to a family from the country’s sizeable Russian minority; her great grandfather, a military man, had moved his whole family there, part of a wave of Russians encouraged to emigrate to Latvia after the USSR absorbed it in 1944. This population movement was part of the so-called Russification of Latvia, which was also pushed through measures such as using the Russian language for officialdom, and imprisoning and deporting Latvian nationalists. Up to 200,000 Latvians were sent to the gulags or imprisoned from 1945–52, depending on which account you read, and by 1959 about 400,000 Russian settlers had arrived. Ethnic Latvians fell to about 60 per cent of the population.

Soboleva was brought up by her grandmother, on whom the Soviet world remains deeply engrained to this day; the family lived in ‘a Russian bubble’, says Soboleva, speaking Russian, watching Russian television and reading Russian books. She attended a Russian school and struggled to learn to speak Latvian. Then in 1991 Latvia gained independence and, instead of giving all its citizens Latvian nationality, opted to make those who had arrived post-1940 non-citizens, and their descendants too. ‘I was given an alien passport,’ Soboleva says. ‘To gain Latvian citizenship, I had to go through a naturalisation process. You know, I understand it. There had been intense Russification so, when the USSR collapsed, the tables turned. Latvia was trying to establish its independence. But as a personal experience, it was quite difficult.’

Latvia joined the European Union in 2004 and in 2008, as soon as she turned 18, Soboleva left for the UK. Previously she had been interested in theatre but, just starting to learn English, she turned to the visual arts, studying for a BA in illustration at Southampton Solent University. Her final project won the Paul Osborne Drawing Prize, and she went on study for an MA in illustration from Manchester School of Art. She became a mother in 2016 and graduated in 2018, and has gone on to establish a successful illustration career, commissioned to create album covers, film posters, and fashion illustration for the celebrated Showstudio portal, as well as making more personal work. When Britain left the EU she applied for and gained British citizenship; for her, it didn’t feel like much of a change, she says, because struggling with the language and not feeling entirely at home is so familiar. ‘I guess I’ve been an immigrant my whole life,’ she says, ‘I always have this feeling of being an outsider, not necessarily in a bad way. It’s just part of me.’

From I have found a light in the darkness by Julia Soboleva (Witty Books)

It’s tempting to interpret her book along these lines, to think about the role aliens may play in it, or the incomprehensibility of those wielding power; it’s tempting too to highlight the fact she found her source images in an encyclopaedia, a neat, authoritative system which she has disturbed and disrupted. I suggest this has something in common with Surrealism, with the desire to question existing power structures and the categories into which the world apparently slots, and she says this reading resonates, that ‘society and culture are just the tip of the iceberg, they don’t really present how things are, how people struggle, how they go about their lives.’

She also brings up the transition to Latvian independence, how surreal it was for Latvians to go to sleep one day in the USSR and wake up in an entirely new country. ‘In those transitional periods, when one world recedes and a new one emerges, a lot of darkness comes up to the surface,’ she says, ‘in the 1990s there was a lot of uncertainty.’ Still, in her work she embraces uncertainty and, as her book title suggests, has found a way to counter the darkness – or at least, to embrace that too. ‘People do sometimes see my images as scary,’ she says with a laugh, ‘but it’s not my intention to scare. I just like exploring this space between light and dark.’

I have found a light in the darkness by Julia Soboleva is published by Witty Books.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)