February, 1888. A small, cheerless room in the south of France. Vincent Van Gogh has come here to escape the grey Paris light, but this doesn’t seem much better. He flings down his heavy pack, takes a seat on a lone wooden chair, unlaces his boots. Yes, you think, have a nap; this is all exhausting. But no – he arranges the beaten-up old shoes on the red-tile floor, and hurriedly sets up his easel. There’s a sense of urgency, mania even, as he puts paint on canvas, his brush moving rapidly back and forth as the wind howls outside and the window rattles in its frame.

‘I can make people feel what it’s like to be alive,’ the artist (Willem Dafoe) says later in At Eternity’s Gate. And indeed, over the course of the film’s two hours, director Julian Schnabel makes us feel what it’s like to live as his Van Gogh. As one might expect, it’s a stressful experience. All the more so since the film is shot on a handheld camera, its jerky motion mirroring the artist’s febrile state. The palette is polarised, either dazzling us with the bright colours of the south, pushed to the extreme, or subduing us with a melancholic blue-grey filter. No even keel for Vincent, or for us. When his ‘frenemy’ Paul Gauguin (Oscar Isaac) asks ‘What’s the rush?’ during another frenzied painting scene, Vincent’s answer is to reel off a list of masters – Franz Hals, Goya, Velázquez, Veronese, Delacroix – who all ‘paint fast, in one, clear gesture’. Long, continuous takes make the film feel correspondingly immediate and organic, even dizzying.

But the flip side to enduring the stress of being Van Gogh is of course the beauty; of seeing the world through his eyes (which the camera often simulates): the wind through wheat or a line of poplars; craggy rocks in a landscape; the texture of scuffed leather boots and terracotta tiles. We’re down in the dirt with him as he lies in a field, smearing earth over his face with relish. And this is the point of Schnabel’s film – why else the need for another Van Gogh biopic, of which there have been three notable versions already. Schnabel – a painter himself – is interested both in this particular artist’s vision, and more broadly in the creative process, and why artists do what they do. ‘These flowers will wither and fade,’ Vincent says as he paints a vaseful; ‘but mine will resist.’

At Eternity’s Gate focuses on the tumultuous last two years of the artist’s life, spent mainly in Arles and in Auvers-sur-Oise. The title comes from that of a painting done in May 1890, a couple of months before his death. Sorrying Old Man (At Eternity’s Gate) was based on earlier drawings, which in turn were based on Hubert von Herkomer’s engraving Sunday at the Chelsea Hospital (1871) – one of the London sources currently on show at Tate’s ‘Van Gogh and Britain’. Van Gogh painted his oil version soon after a nine-week period at the asylum in Saint-Remy de Provence, and seems to have added the second part of the title for this version alone.

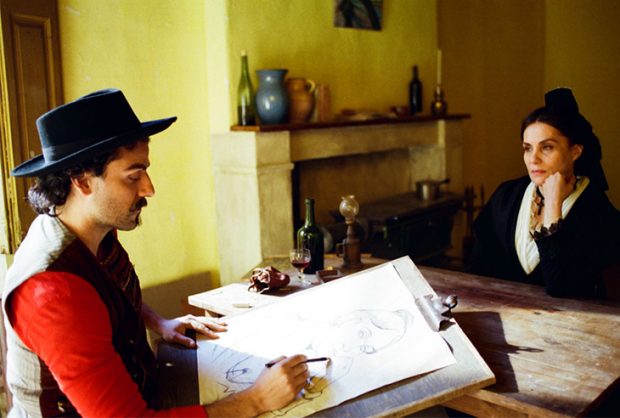

Oscar Isaac as Paul Gauguin and Emmanuelle Seigner as Marie Ginoux in ‘At Eternity’s Gate’ (2018)

Schnabel resists the temptation to dramatise the most famous incident of this period – and of the artist’s life – his ear-severing, instead taking his cue from Greek tragedy and having the self-mutilation happen off-stage. Other potential clichés are nicely side-stepped. Up until the very end, the only sight we get of sunflowers is when Vincent tramps through a dismal field of them, dried up and devastated like the scorched tree stumps of Paul Nash’s war landscapes. Or so many sorrowing old men. Likewise, a conversation between Gauguin and Van Gogh about art and nature is saved from pomposity and affectation by humour – the two men are gazing at the glorious Provencal countryside, but taking a companionable piss while they’re at it. ‘We have to change entirely the relation between painting and what you call nature,’ says the bullish Gauguin, undoing his trousers. ‘The Impressionists… they’re out of it.’ ‘I still think Monet’s pretty good,’ Vincent meekly protests.

There is a touch of Wes Anderson in the casting of cameo roles here, giving us moments of double-recognition as characters played by familiar faces emerge from Van Gogh’s portraits – Emmanuelle Seigner as Madame Ginoux, proprietress of the Café de la Gare; Mathieu Amalric as Doctor Paul Gachet – giving the film not one but two Bond villains (I kept expecting Mads Mikkelsen’s priest to start weeping blood as he interrogates a broken Van Gogh about why he paints).

Dafoe has form playing artistically named characters with lopped-off appendages – see his thumb-less thief, David Caravaggio, in The English Patient. He also appeared (as an electrician) in Schnabel’s other artist biopic, Basquiat, in 1996. More seriously, though, his lead in Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ will have been useful preparation for this role as persecuted misfit. Even Gauguin seems not to understand his art: ‘Your surface looks like it’s made out of clay. It’s more like a sculpture than a painting.’ Vincent’s breakdown at the news that Gauguin is leaving Arles was shot in the Alyscamps, the ruined Roman necropolis where Van Gogh and Gauguin painted together in October 1888. (Alyscamp, incidentally, meaning Elysian Fields – or eternity.) There are many moving moments in this film, for which Dafoe well deserves his Oscar nomination, but there’s something particularly powerful about seeing this unappreciated radical lost amid the remnants of the classical world. ‘Maybe God made me a painter for people who aren’t born yet,’ Dafoe’s Vincent says, his milky-blue eyes like a seer’s.

At Eternity’s Gate (2018) is on general release in the UK and available on demand. Dir. Julian Schnabel. 12A cert. 111 mins approx.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze