In public spaces throughout Iran, two portraits hang side by side: the bearded visages of Ruhollah Khomeini, who became supreme leader of Iran in 1979, and Ali Khamenei, who succeeded him ten years later and remains head of state today. They are the avatars of the patriarchal theocracy to which Iranians have been subject since the Iranian revolution. When schoolgirls scrawled slogans such as ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ on photographs of the two men during the protests that exploded after the 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died in the custody of the ‘morality police’ in 2022, it was tantamount to heresy: those who criticise the supreme leader can face years in prison.

At Cooke Latham Gallery in Battersea, two mirrors are placed high on the wall directly opposite the front door of the exhibition space. They’re easy to miss; if you do glimpse them, you might assume their positioning is some kind of ironic gag. In fact, they are part of ‘2002’, an exhibition by the British-Iranian artist Laila Tara H (b. 1995), and their unassuming placement is a fine example of her ability to comment at once sharply and obliquely on Iranian society. Sitting in place of the portraits of the two supreme leaders, the mirrors are both an emancipatory, anti-autocratic gesture and an invitation to the viewer to look at themselves and appreciate the freedoms they currently enjoy.

Tara H is best known for exploring and expanding the Persian miniature tradition, and most of the work in ‘2002’ comprises works on paper that show off her deft, detailed brushwork. The imagery is not broad in range but becomes more powerful – and mysterious – through repetition: what appears to be the disembodied head of an imperious man, duplicated many times across and between canvases, is actually the head of a woman, hailing from a tradition of depicting androgynous women at a time when hair was far less politically charged. (Amini was arrested in the first place for not wearing her hijab in the manner mandated by the government.) In Conjunction I (2024), these heads, whose invisible hair disappears into the canvas, are interspersed with flames that take a pointedly similar shape. The ostensibly genderless heads take on a very gendered rage.

Installation shot of Conjunction I and Conjunction II (2024) by Laila Tara H. Photo: Ben Deakin; courtesy the artist and Cooke Latham Gallery; © the artist

The piece forms half of an understated diptych with Conjunction II (2024), in which the recurrent symbol is more hopeful: a tulip, painted with brushes consisting of a single hair taken from a cat, a squirrel or a mongoose. Juxtaposed with the flames, the flowers suggest rebirth; the empty space on the hemp paper canvas seems to provide room for proliferation. The paper is never occluded by the frame, even partially; painstakingly produced by the Kagzi people, India-based paper-makers with roots in what is now Uzbekistan, it is not so much a medium for the art as a part of the art itself.

Detail from Conjunction II (2024) by Laila Tara H. Photo: Ben Deakin; courtesy the artist and Cooke Latham Gallery; © the artist

Many of the frames in the show call attention to themselves: some are rhomboid rather than rectangular, others are shaped and arranged to tell a particular story. Sleep, wake, wash, task, check, work, panic, task, check, scroll, work, retreat, wash, sleep, wake (2024) is a thoughtfully constructed critique of domestic servitude: two rectangular frames, in which a set of sleepy Janus-faced heads are painted on to paper that sits atop carefully creased velvet, resemble pillows, with any hint of somnolence undercut by cowbells and steel moulds of washing-up gloves fixed to the walls: a woman’s work, it seems to suggest, is never done. Each element of the composition, like the rest of the art on display here, has a lightness of touch and, when viewed from a distance – though you may have to squint a little – the various frames and accoutrements, which include what appear to be a set of buttons and a belt buckle, together resemble the headless body of a man in shirt and trousers.

Installation view of Leftovers I and Leftovers II (2024) by Laila Tara H. Photo: Ben Deakin; courtesy the artist and Cooke Latham Gallery; © the artist

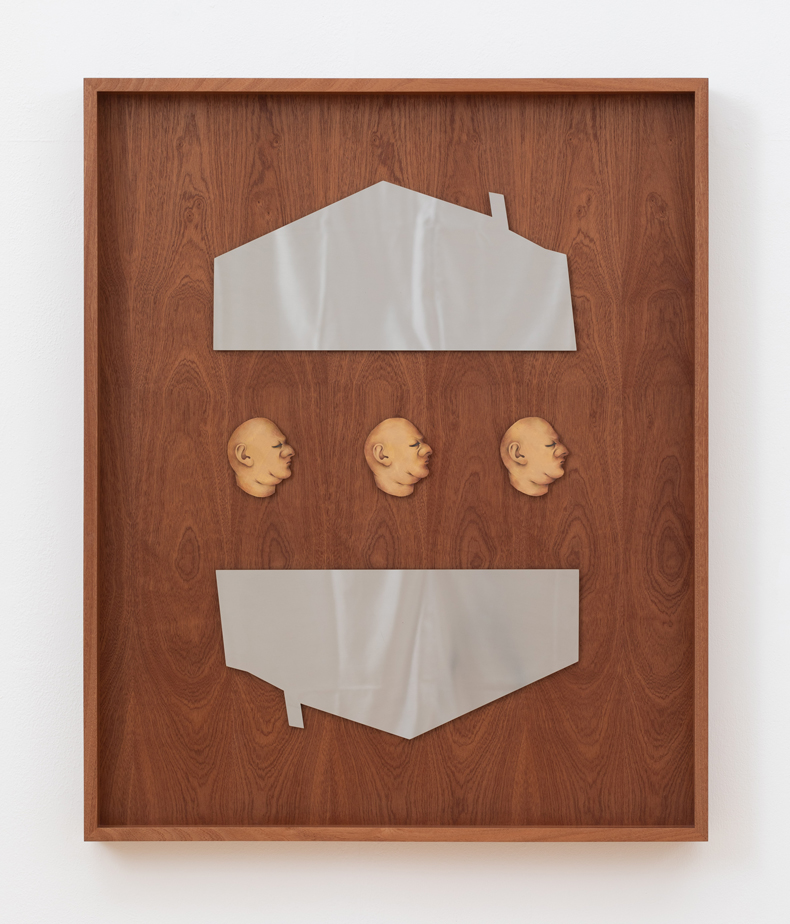

Tara H’s comments on patriarchy are more convincing than some of her anti-imperialist work: in Entry point (convincing power of yum) (2024), for example, three bald heads are sandwiched between two bap-shaped cut-out mirrors. It is intended as a comment on the ‘Golden Arches’ theory – the idea, first floated by the commentator Thomas Friedman, that no two nations with a McDonald’s would ever go to war with each other. But the artwork is so inscrutable that her point never quite comes across, not least because the baps are oddly angular and for some reason seem to sport chimneys. It’s not clear whether too much thought has gone into the piece or not enough.

Installation view of Entry point (convincing power of yum) (2024) by Laila Tara H. Photo: Ben Deakin; courtesy the artist and Cooke Latham Gallery; © the artist

Still, given the seriousness of some of the themes the works touch on, this is a refreshingly playful show, full of ideas that complement the artist’s skill as a miniaturist. Her eye for placement is visible not just as you enter, with the mirrors, but also as you leave: a fire exit sign, which you could almost mistake for a permanent feature of the gallery, points to the anxieties, perhaps even the nihilism, of a generation. We might be waiting for the world to burn, but in the meantime we’ll always have wit.

Installation view of Route II (2024) by Laila Tara H. Photo: Ben Deakin; courtesy the artist and Cooke Latham Gallery; © the artist

‘2002’ is at Cooke Latham Gallery, London, until 19 July.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Apollo at 100