Looking at the recently announced shortlist for this year’s Art Fund Museum of the Year prize, you might think that civic museums and galleries across the UK were in rude health. The contenders are a fascinating bunch, with museums from every nation and no representatives from London.

But take a closer look at the list and you might notice something odd. For not a single museum on the shortlist is what we would recognise as a local authority museum. Two of the shortlisted museums are branches of national museums: St Fagans Museum (part of National Museum Wales) and HMS Caroline in Belfast (a branch of the National Museum of the Royal Navy). A third, the V&A Dundee, is a collaboration between the national museum in London, the city’s two universities and the local council. The remaining candidates are the Pitt Rivers Museum, operated by Oxford University, and Nottingham Contemporary, which is an independent trust.

Local authorities are at the heart of the story of museums in the UK, playing a major role as funders of many of the country’s most prominent museums, from the Kelvingrove in Glasgow to the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter and hundreds in between. England alone has some 397 local authority museums. Indeed, councils have been vital players in the museums scene since the birth of the modern museum in the 19th century. Giles Waterfield’s excellent history of museums, The People’s Galleries: Art Museums and Exhibitions in Britain, 1800–1914, charts the important – though sometimes reluctant – role that local authorities played in building and maintaining them.

The absence of local authority museums from the Art Fund Museum of the Year shortlist would once have been unusual. In 2019, it is a sign of the times – an indication of the weakening relationship between local authorities and museums. And the reason for this change is money.

Put simply, austerity has not spared the arts. In the last 10 years local authority funding for museums has declined rapidly. Between 2010 and 2016, local authority spending on museums and galleries in England fell by a third in real terms, while recently published figures from the Budapest Observatory show that the UK’s local authority budget for culture is just over 1 per cent of total municipal spending, compared with over 6 per cent in Latvia and over 4 per cent in France, making the UK’s proportional spending on culture the lowest in Europe.

Museums are increasingly treated by cash-strapped councils as a major liability. Unlike bin collection, social services, and even libraries, they are a non-statutory service, so there is no legal obligation to fund them. While most local authorities are still keen – for reasons of civic pride – on the idea of having a good museum, the scale of cuts over the past ten years has forced them to rethink their involvement in the field.

Across the UK, councils are now involved in a scrabble to get rid of responsibility for their museums. There is much talk about identifying new models for providing these services. One popular method is to offload the museum and its staff on to an independent trust which is no longer formally the responsibility of the council. An independent trust model has certain attractions: the museums have more freedom to pitch for philanthropic and grant funding, are able to set their own rates of pay, and can keep income raised from commercial functions, such as the café or venue hire, where previously this would have been lost to the local authority coffers.

The shift to trust status has been rapid. According to the 2017 DCMS Mendoza Review of Museums, the number of charitable trusts operating museums in England increased from six in 2004 to 64 in 2016. Major museum services such as Sheffield and York in England and Glasgow and Perth in Scotland have adopted this status among many others.

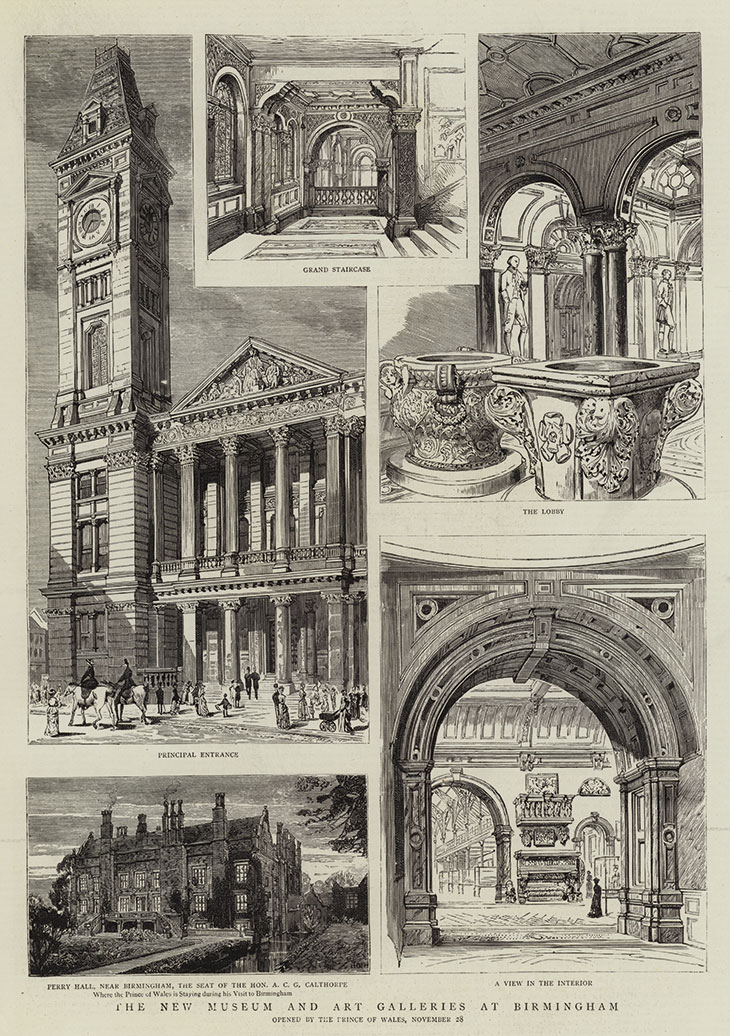

Illustrations of ‘The New Museum and Art Galleries at Birmingham’, published in The Graphic on the day of their opening by the Prince of Wales, 28 November, 1885. Photo: © Look and Learn/Illustrated Papers Collection/Bridgeman Images

Unfortunately, trust status is little more than a piece of managerial sleight of hand. These museums are independent in name only. All are still reliant for the vast majority of their funding on a local authority grant, and most would fold instantly without ongoing council support. Indeed, some of the largest former local authority trusts in the country, such as Birmingham and Derby, are those facing the most acute financial predicament as their parent councils back away from long-term funding.

Elsewhere, lack of support from the local authority means an even more abrupt ending, with the closure of museums altogether. Lancashire County Council decided in 2016 to close five museums, including the Museum of Lancashire and some of the best-preserved working mills in the UK (four have since reopened on a part-time basis, but their long-term future remains uncertain). In total, some 64 museums closed in the UK between 2010 and 2016, most of them due to local authority cuts.

So what we’re witnessing at the moment is not merely a bit of restructuring. It is a widespread retreat of local authorities from the delivery of museum services. Does this shift matter? Does anyone actually care whether or not their local museum is run by their local authority? After all, local authorities have sometimes been their own worst enemies when operating their museums – think, for example, of Northampton Borough Council, which flogged off its star object, the early Egyptian Sekhemka statue in 2014, against the wishes of local people, museum staff and even the Egyptian government. Or the many local authority museums that have moved achingly slowly to adapt to the online world, with web pages and social-media content dictated by clunky centralised communications operations.

I would argue that we shouldn’t be so quick to embrace this retreat. The reasons are, again, largely to do with money. As of 2015 local authorities still provided some £200m of funding to museums in England. That’s not to be sniffed at. But more than that – there really aren’t many other options. This is because many local authority museums are among the largest and most established museums in the country. They have long histories and vast collections. Norfolk Museums Service, which has a collection of more than three million objects, is typical of the sector. It has everything: superb fine art, such as the recently exhibited Paston Treasure; archaeological collections that include Seahenge, the marshy cousin of Stonehenge; social and military history collections that include a huge 16m by 8m bloodstained French tricolour captured by the British navy during the Napoleonic wars. These are items and collections of not just regional importance, but national and international value. Arts Council England currently designates some 140 collections across England as being of national importance – but the responsibility for conserving, storing, researching and displaying these collections lies with their local authority owners.

The Paston Treasure (c. 1663), unknown artist (Dutch school). Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery

Local authority museums also inhabit some of the grandest civic buildings at the heart of our towns and cities. The overheads of caring for these assets are enormous – and that’s before you get to paying for staff to bring them to life for the public. All of those costs combined mean that our civic-museum model will always rely on a long-term strategic partner – in other words: government.

There has been much talk of alternative sources of income – from philanthropists and donors, and from enlarged cafes and commercial operations. But, in reality, museums have put in an enormous amount of effort to increasing these sources of income in recent years with moderate and fluctuating results. That is particularly the case for institutions outside London. While central government provides welcome support to many local authority museums via Arts Council England, the total on offer is just a fraction of what local authorities themselves pay towards museums. So it seems that civic museums in the UK are tied to the fortunes of local government in the UK for the long run – for richer, for poorer.

But there’s more to it than just money. Museums are more popular than ever in the UK – and local authority museums certainly aren’t immune to this success. In May, Leeds, the largest local authority museum service in England, announced that it had had 1.7m visitors in 2018 – an increase of 370 per cent in the last 15 years. That kind of success can be driven from within local government, by combining great exhibitions with good tourism campaigns and great partnerships with schools and community groups.

The multiplier effect that local authorities can bring to their museums can help make a museum a success. But it works both ways. Increasingly, local authorities are looking to their museums and cultural spaces as the catalysts for renewal. They are seeing how museums can help breathe life back into town centres that are suffering from the high street downturn; or support elderly and vulnerable residents through outreach programmes; or promote inward investment in their area. And it is perhaps this that gives us some cause for optimism for the future of these great institutions: that museums aren’t a liability at all – they can be a town’s greatest asset.

Alistair Brown is policy officer at the Museums Association.

From the June 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

What hope for civic museums?

The central sculpture hall of the Glasgow (now Kelvingrove) Art Gallery and Museum, newly opened for the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1901

Share

Looking at the recently announced shortlist for this year’s Art Fund Museum of the Year prize, you might think that civic museums and galleries across the UK were in rude health. The contenders are a fascinating bunch, with museums from every nation and no representatives from London.

But take a closer look at the list and you might notice something odd. For not a single museum on the shortlist is what we would recognise as a local authority museum. Two of the shortlisted museums are branches of national museums: St Fagans Museum (part of National Museum Wales) and HMS Caroline in Belfast (a branch of the National Museum of the Royal Navy). A third, the V&A Dundee, is a collaboration between the national museum in London, the city’s two universities and the local council. The remaining candidates are the Pitt Rivers Museum, operated by Oxford University, and Nottingham Contemporary, which is an independent trust.

Local authorities are at the heart of the story of museums in the UK, playing a major role as funders of many of the country’s most prominent museums, from the Kelvingrove in Glasgow to the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter and hundreds in between. England alone has some 397 local authority museums. Indeed, councils have been vital players in the museums scene since the birth of the modern museum in the 19th century. Giles Waterfield’s excellent history of museums, The People’s Galleries: Art Museums and Exhibitions in Britain, 1800–1914, charts the important – though sometimes reluctant – role that local authorities played in building and maintaining them.

The absence of local authority museums from the Art Fund Museum of the Year shortlist would once have been unusual. In 2019, it is a sign of the times – an indication of the weakening relationship between local authorities and museums. And the reason for this change is money.

Put simply, austerity has not spared the arts. In the last 10 years local authority funding for museums has declined rapidly. Between 2010 and 2016, local authority spending on museums and galleries in England fell by a third in real terms, while recently published figures from the Budapest Observatory show that the UK’s local authority budget for culture is just over 1 per cent of total municipal spending, compared with over 6 per cent in Latvia and over 4 per cent in France, making the UK’s proportional spending on culture the lowest in Europe.

Museums are increasingly treated by cash-strapped councils as a major liability. Unlike bin collection, social services, and even libraries, they are a non-statutory service, so there is no legal obligation to fund them. While most local authorities are still keen – for reasons of civic pride – on the idea of having a good museum, the scale of cuts over the past ten years has forced them to rethink their involvement in the field.

Across the UK, councils are now involved in a scrabble to get rid of responsibility for their museums. There is much talk about identifying new models for providing these services. One popular method is to offload the museum and its staff on to an independent trust which is no longer formally the responsibility of the council. An independent trust model has certain attractions: the museums have more freedom to pitch for philanthropic and grant funding, are able to set their own rates of pay, and can keep income raised from commercial functions, such as the café or venue hire, where previously this would have been lost to the local authority coffers.

The shift to trust status has been rapid. According to the 2017 DCMS Mendoza Review of Museums, the number of charitable trusts operating museums in England increased from six in 2004 to 64 in 2016. Major museum services such as Sheffield and York in England and Glasgow and Perth in Scotland have adopted this status among many others.

Illustrations of ‘The New Museum and Art Galleries at Birmingham’, published in The Graphic on the day of their opening by the Prince of Wales, 28 November, 1885. Photo: © Look and Learn/Illustrated Papers Collection/Bridgeman Images

Unfortunately, trust status is little more than a piece of managerial sleight of hand. These museums are independent in name only. All are still reliant for the vast majority of their funding on a local authority grant, and most would fold instantly without ongoing council support. Indeed, some of the largest former local authority trusts in the country, such as Birmingham and Derby, are those facing the most acute financial predicament as their parent councils back away from long-term funding.

Elsewhere, lack of support from the local authority means an even more abrupt ending, with the closure of museums altogether. Lancashire County Council decided in 2016 to close five museums, including the Museum of Lancashire and some of the best-preserved working mills in the UK (four have since reopened on a part-time basis, but their long-term future remains uncertain). In total, some 64 museums closed in the UK between 2010 and 2016, most of them due to local authority cuts.

So what we’re witnessing at the moment is not merely a bit of restructuring. It is a widespread retreat of local authorities from the delivery of museum services. Does this shift matter? Does anyone actually care whether or not their local museum is run by their local authority? After all, local authorities have sometimes been their own worst enemies when operating their museums – think, for example, of Northampton Borough Council, which flogged off its star object, the early Egyptian Sekhemka statue in 2014, against the wishes of local people, museum staff and even the Egyptian government. Or the many local authority museums that have moved achingly slowly to adapt to the online world, with web pages and social-media content dictated by clunky centralised communications operations.

I would argue that we shouldn’t be so quick to embrace this retreat. The reasons are, again, largely to do with money. As of 2015 local authorities still provided some £200m of funding to museums in England. That’s not to be sniffed at. But more than that – there really aren’t many other options. This is because many local authority museums are among the largest and most established museums in the country. They have long histories and vast collections. Norfolk Museums Service, which has a collection of more than three million objects, is typical of the sector. It has everything: superb fine art, such as the recently exhibited Paston Treasure; archaeological collections that include Seahenge, the marshy cousin of Stonehenge; social and military history collections that include a huge 16m by 8m bloodstained French tricolour captured by the British navy during the Napoleonic wars. These are items and collections of not just regional importance, but national and international value. Arts Council England currently designates some 140 collections across England as being of national importance – but the responsibility for conserving, storing, researching and displaying these collections lies with their local authority owners.

The Paston Treasure (c. 1663), unknown artist (Dutch school). Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery

Local authority museums also inhabit some of the grandest civic buildings at the heart of our towns and cities. The overheads of caring for these assets are enormous – and that’s before you get to paying for staff to bring them to life for the public. All of those costs combined mean that our civic-museum model will always rely on a long-term strategic partner – in other words: government.

There has been much talk of alternative sources of income – from philanthropists and donors, and from enlarged cafes and commercial operations. But, in reality, museums have put in an enormous amount of effort to increasing these sources of income in recent years with moderate and fluctuating results. That is particularly the case for institutions outside London. While central government provides welcome support to many local authority museums via Arts Council England, the total on offer is just a fraction of what local authorities themselves pay towards museums. So it seems that civic museums in the UK are tied to the fortunes of local government in the UK for the long run – for richer, for poorer.

But there’s more to it than just money. Museums are more popular than ever in the UK – and local authority museums certainly aren’t immune to this success. In May, Leeds, the largest local authority museum service in England, announced that it had had 1.7m visitors in 2018 – an increase of 370 per cent in the last 15 years. That kind of success can be driven from within local government, by combining great exhibitions with good tourism campaigns and great partnerships with schools and community groups.

The multiplier effect that local authorities can bring to their museums can help make a museum a success. But it works both ways. Increasingly, local authorities are looking to their museums and cultural spaces as the catalysts for renewal. They are seeing how museums can help breathe life back into town centres that are suffering from the high street downturn; or support elderly and vulnerable residents through outreach programmes; or promote inward investment in their area. And it is perhaps this that gives us some cause for optimism for the future of these great institutions: that museums aren’t a liability at all – they can be a town’s greatest asset.

Alistair Brown is policy officer at the Museums Association.

From the June 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Share

Recommended for you

How should private collectors and public museums work together?

This year’s TEFAF Art Symposium looked at an old but not unproblematic relationship

Forum: Should UK museums reintroduce entrance charges?

As some UK museums face cuts of up to 40 per cent, Bill Ferris and Alistair Brown discuss whether they should consider charging entrance fees again.

Can a local authority really get rid of 90 per cent of its art?

Once part of a pioneering schools loan programme, most of Hertfordshire County Council’s art collection looks set to be flogged off